It is not commonly known that 14 large asteroids in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter were discovered by Herman Goldschmidt, a French-Jewish astronomer and artist, over a remarkable decade of scientific achievement beginning in 1852.

It is not commonly known that 14 large asteroids in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter were discovered by Herman Goldschmidt, a French-Jewish astronomer and artist, over a remarkable decade of scientific achievement beginning in 1852.

Since only 20 asteroids had been known to science before Goldschmidt’s heavenly investigations, which he began with only a crude glass pointed upwards from a Paris rooftop, he won the French Legion of Honour and many other awards. Upon his death in 1866, the London Jewish Chronicle carried an extensive obituary that summarized his then-notable career, which is as forgotten today as any of the “little planets” that he charted and named.

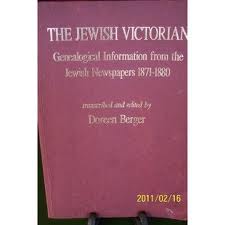

Goldschmidt’s obit and many thousands of other items of interest to London’s large Jewish community of the 1860s have been reprinted in the recently-released second volume of The Jewish Victorian: Genealogical Information from the Jewish Newspapers 1861-1870, compiled by Doreen Berger.

Like its predecessor volume which covered the 1870s, Doreen Berger’s new volume — The Jewish Victorian: Genealogical Information from the Jewish Newspapers 1861-1870 (Robert Boyd, publisher) — offers an invaluable window onto the Jews of London and the British provinces of the middle Victorian period. Typeset in small type and set in three columns, each of its 396 pages is crammed with family, social and historical details about British Jewry.

Berger, who also deserves a medal for the Herculean task of transcribing and editing, has included everything of interest to a genealogist or historian. More than a compendium of births, bar mitzvahs, marriages and deaths, The Jewish Victorian presents countless riveting accounts of court proceedings, crimes, fires, gruesome accidents, abductions of Jewish children and other occurrences that bring the era to life. Many pages recount episodes in the lives of the Montefiores, Sassoons, Rothschilds, Disraelis and other well-known personages.

Thomas Jackson, an East Holborn pawnbroker, was obliged to give evidence in court on a Saturday; but declined to sign his name to a deposition because “it is our Sabbath.” Ordered to sign before leaving the courtroom, he replied, “Then I’ll stay until our Sabbath is over.” Threatened with imprisonment for seven or 14 days, Jackson ultimately signed: the Jewish Chronicle noted that a Newcastle newspaper reported the incident as “an amusing scene.”

A memorable bar mitzvah occurred at the Portland Street Synagogue in 1869, the Chronicle reported. “An inmate of Jew’s Deaf & Dumb Home, having attained the age of bar mitzvah, was called to the Sepher, and pronounced blessings in an audible voice. The boy was what is called a deaf-mute. . . . We need scarcely say the incident evinced considerable emotion. After the service, many persons crowded round the Bar Mitzvah boy and congratulated him.”

A memorable bar mitzvah occurred at the Portland Street Synagogue in 1869, the Chronicle reported. “An inmate of Jew’s Deaf & Dumb Home, having attained the age of bar mitzvah, was called to the Sepher, and pronounced blessings in an audible voice. The boy was what is called a deaf-mute. . . . We need scarcely say the incident evinced considerable emotion. After the service, many persons crowded round the Bar Mitzvah boy and congratulated him.”

Numerous entries help us reconstruct the remarkable career of an obscure Jewish traveler, the Moldavian-born Joseph Israel, who changed his name to Benjamin Traveler (II) in honour of his medieval antecedent, Benjamin of Tudela. Seeking remnants of the lost tribes of Israel, Benjamin traversed continents, published several books of travels, and died in 1864 at the age of 40.

Anyone doing research into British-Jewish ancestors will find The Jewish Victorian both fascinating and indispensible. Kudos to Ms. Berger, who has already begun compiling a third volume for the 1880s. ♦

© 2004