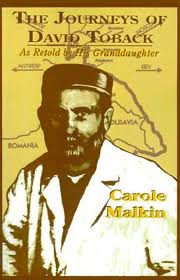

It is sometimes said that heredity is destiny — a phrase with some apparent truth in The Journeys of David Toback, an old (Yiddish) diary edited (in English) by Carole Malkin and published by Schocken Books.

It is sometimes said that heredity is destiny — a phrase with some apparent truth in The Journeys of David Toback, an old (Yiddish) diary edited (in English) by Carole Malkin and published by Schocken Books.

For David Toback, who became bar-mitvahed in a dirt-poor Ukrainian village in 1888, the pair of tefillin that his father gave him that day would help shape his destiny. The tefillin were 132 years old and had belonged to his great-grandfather, who was revered as a tzaddik.

At home after David reads his bar mitzvah portion, his mother weeps because she has no means to make a party. But that evening, friends and relatives arrive with pots of potatoes and cabbage, roasted lamb and loaves of bread. As they are about to make a blessing, the sound of horses’ hooves announces the arrival of a large coach pulled by four black horses.

Several Hasidim emerge in long black kaftans, fur hats, thick beards and curled peyes, including two famous rabbis and an elderly rav of even more awesome reputation. They have come to honour the great-grandfather of the boy who would be putting on his tefillin for the first time.

The villagers tremble to be near such scholars, but the kindly Hasidim are friendly with everyone, their faces shining as they discourse on Torah. The rav, having heard that David had been studying Mishnah, says he would like to examine him. As David steps forward, his feet resisting, his face burning, his heart thumping, the rav whispers to him not to be afraid.

“The moment he touched me I felt a little calmer. I noticed my mother staring at me and suddenly I felt confident that I could answer anything he asked — and that was how it happened. For each question a response would leap into my head and begin to develop, first one way, then another. All the ideas I thought of were new to me. I could hardly believe how quiet everyone was and how they stared at me, and I sensed it was with great respect. This was particularly so when the rav stood up, came over to me, and kissed me on the forehead.

“My mother’s joy was extreme. She was unable to contain herself and flung herself on me and began to weep. . . . The rav addressed her and my father in a solemn tone. ‘Your child is not an ordinary person. Not only is he intelligent, but he has a pure heart. You must see to it that he studies with good teachers, even if you have send him away from you.’”

This moving encounter is one of many excellent scenes in The Journeys of David Toback, first published by Schocken in 1981 and again by Walker & Co. in 1992. In his old age, Toback, then a retired butcher in New York, wrote his life’s story, certain it would never be read. His granddaughter, Carole Malkin, edited and polished the manuscript into a charming and riveting narrative that captures the gritty texture of Jewish life in the Russian Pale in the 1890s.

As the rav predicted, David is sent to a yeshiva, but by degrees he loses his purity, gaining worldly experience through many intriguing adventures. At fifteen, his parents want him to come home and marry a poor village girl, but he escapes from both home and yeshiva. His journeys take him through many small villages as well as to the cities of Kremenets, Proskurov, Kishinev and Cotu Mori. The book ends with his passage to America, an extraordinary episode in itself.

Like many Jewish memoirs, this one was written after a tragedy: Toback’s daughter Tzerl had jumped from a roof and killed herself. A year later he filled five notebooks with Yiddish prose, certain all the while that no one would care about an old man and his memories. “I’m going to put it all in the closet, and when I die it goes into the garbage,” he wrote. But fortunately, as with many of his adventures, a surprise ending lay in store, preserving his tale for posterity. ♦

© 2005