JUDY HOLLIDAY OBIT, 1965

From the Canadian Jewish Review, June 18, 1965

Judy Holliday, an actress whose professional career was all comedy and whose later private life was all tragedy, introduced the word “couth” to the English language.

Judy Holliday, an actress whose professional career was all comedy and whose later private life was all tragedy, introduced the word “couth” to the English language.

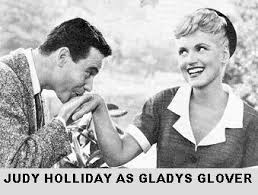

The etymological creation was part of her portrayal of one of the most memorable of a noted list of dumb blondes who turned out, upon analysis to be pretty smart cookies, after all, writes M.C. Blackman, in the New York Herald Tribune, Miss Holliday’s characterization of Billie Dawn in 1946 in Garson Kanin’s Born Yesterday which was made into a movie after four years on Broadway, won her an Oscar in 1951 as the top actress of 1950, and launched her upon a career of stage and screen.

She could never get away from roles similar to the one that first brought her success. She summed up her career of parts once rather sadly: “You see them walk on the stage and you laugh.”

In Born Yesterday, she portrayed the part of the doxie of a rough-and-tumble junkman named Harry Brock, played with wonderful skill by the late Paul Douglas. Billie Dawn longed for someone better, someone “couth.”

Webster didn’t — and still doesn’t — recognize the word, except as archaic meaning “known, familiar.” That wasn’t what Billie Dawn meant at all. According to her dumb, blonde logic — which grammarians find hard to refute — she longed for a companion who was the opposite of “uncouth” which means boorish, rude, and unrefined. She wanted what Webster gives as the antonym of “uncouth” — graceful, polished, refined.

Webster didn’t — and still doesn’t — recognize the word, except as archaic meaning “known, familiar.” That wasn’t what Billie Dawn meant at all. According to her dumb, blonde logic — which grammarians find hard to refute — she longed for a companion who was the opposite of “uncouth” which means boorish, rude, and unrefined. She wanted what Webster gives as the antonym of “uncouth” — graceful, polished, refined.

In the end, Billie Dawn taught the uncouth junk dealer the meaning of democracy and proved she was not as dumb as she looked and acted — though not as smart as her creator, Judy Holliday, who had an IQ of 172, and read Stendhal and Proust.

Her last Broadway play, after a series of stage and screen successes, was Hot Spot in 1963, while she was in the midst of a five-year battle with cancer.

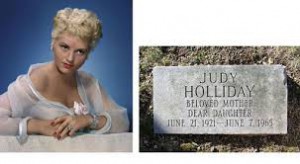

Recently she had been working on song lyrics with jazz musician Gerry Mulligan, until she entered Mount Sinai Hospital on May 26, when her case was believed to be terminal, says the New York Herald Tribune. She died quietly in her sleep at 5 a.m., on June 7, 1965. She would have been forty-two on June 21.

She had been living with her mother, Mrs. Helen Tuvini, and her son Jonathan, in the Dakota, a large old apartment building on Central Park West. She had been divorced since 1957 after a nine-year marriage to cellist David Oppenheim.

She had been living with her mother, Mrs. Helen Tuvini, and her son Jonathan, in the Dakota, a large old apartment building on Central Park West. She had been divorced since 1957 after a nine-year marriage to cellist David Oppenheim.

Miss Holliday literally backed into the life of producer Max Gordon who put her, in an emergency, into the play that made her famous. Trapped in a rainstorm in the Village, she ducked down a stairway leading to a cellar. A man opened the door and invited her to come in out of the wet. She backed in, not knowing what to expect.

The place was the Village Vanguard, and the man was the owner Mr. Gordon. He bought her a soft drink, and she asked him why he didn’t get some entertainment in his club.

The conversation led to the appearance of The Revuers, with Adolph Green, Betty Comden, Judy, and a couple of others. Miss Holliday went to Hollywood for some bit parts, and returned to appear in a Broadway comedy named Kiss Them for Me, based on the novel, Shore Leave, by Frederick Wakeman. She won the Derwent Prize of $500 with a scroll proclaiming her “the best supporting actress of 1945.”

She lived on the $500 until Max Gordon, now a producer with some fifty shows to his credit, remembered her performances in Kiss Them for Me, when Jean Arthur became ill during the rehearsal of Born Yesterday for an appearance in Philadelphia, says the New York Herald Tribune. He sent for her. Miss Holliday worked at memorizing the part of Billie Dawn almost continuously for three days and nights, performed perfectly and came to New York and instant success.

After the movie version won her the award of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, there followed a number of films including The Marrying Kind, It Should Happen to You, Phfft and The Solid Gold Cadillac.

After the movie version won her the award of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, there followed a number of films including The Marrying Kind, It Should Happen to You, Phfft and The Solid Gold Cadillac.

In 1956 she opened in her second great Broadway musical Bells Are Ringing, with Sydney Chaplin. In it she portrayed a backstage switchboard operator, a role which she filled in real life, in Orson Welles’ Mercury Theater — not for money but because she was just out of school and stagestruck. Bells Are Ringing won her the Antoinette Perry Award, and she later made a movie version.

She also made another Hollywood film, Full of Life, before doing her last Broadway play, The Hot Spot.

Dumb? Miss Holliday once said in an interview: “We actors, like most highly specialized professionals tend to live in a world of our own. We become involved in developing our skill, polishing our technique, and in general we cultivate an ‘artist’s immunity’ to the outside world. It seems to me that this is a mistake we make. Do you become less of an artist because you refuse to accept inflation, war, and lynching? I don’t think so. We can’t turn to the theater page first.”

With sentiments such as these, it was small wonder that Miss Holliday became an enthusiastic joiner of causes. This led to her being called before the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee to whom she frankly admitted she had unwittingly contributed, says the New York Herald Tribune, to some subversive and Communist front organizations.

Reverting in part to her dumb-blonde actress roll, she told the committee that she was so confused she had hired investigators to investigate herself because “I wanted to know what I had done” in supporting certain organizations.

Cancer first intruded upon her theatrical life in 1960. She was trying out in Philadelphia with Laurette in the autumn when she had to enter a hospital for the removal of a throat tumor. The play was canceled. The disease plagued her intermittently ever since.

Miss Holliday was born Judith Tuvim, an only child in New York City. Her father Abraham Tuvim, a tall solemn man whose business was fund-raising for Israel, died in 1958. Tuvim was taken from Yom Tuvim, Hebrew words for holidays, and Judy adopted an English translation of it during her first stay in Hollywood because people were always misspelling or mispronouncing her name.

Miss Holliday was born Judith Tuvim, an only child in New York City. Her father Abraham Tuvim, a tall solemn man whose business was fund-raising for Israel, died in 1958. Tuvim was taken from Yom Tuvim, Hebrew words for holidays, and Judy adopted an English translation of it during her first stay in Hollywood because people were always misspelling or mispronouncing her name.

Her piano-teacher mother left the audience of a Fanny Brice comedy for New York’s Lying-In Hospital just in time for Judy’s birth. At the age of four years, Judy was taking ballet lessons. She attended public schools, and was graduated from high school before she found the switchboard spot at the Mercury Theatre, says the New York Herald Tribune. Her mother and son are the only survivors.

One hundred other persons tried to get into the Frank E. Campbell Funeral Church, at 81st Street, and Madison Avenue, where the services were held, but had to remain outside because of lack of space. Among the mourners at the 26-minute, non-denominational service were David Oppenheim, her former husband, and Sydney Chaplin, who played opposite her in the musical, Bells are Ringing.

Miss Holliday lay in a closed mahogany coffin covered with a blanket of roses, carnations, and peonies. Among those who sent floral tributes were Shelley Winters, Katharine Hepburn, Spencer Tracy, Harold Prince, Vincent Sardi Jr., Dave Brubeck and Goddard Lieberson.

Among the mourners were: Abe Burrows, Gertrude Berg, Howard Teichman, Morton Gottlieb, Jule Styne, Betty Comden, and Adolph Green. Miss Holliday entered show business with the latter two in 1938 at the Village Vanguard.

The silence of the chapel was broken by the Guarnerius Quartet from another room, which opened the service by playing the adagio movement of the Mendelssohn A Minor Quartet, says the New York Herald Tribune. Men lowered their heads and women dabbed at their eyes.

Fighting back the tears during the service were Miss Holliday’s son, Jonathan, aged twelve years, and her mother Mrs. Helen Tuvim.

Dr. Algernon Black, president of the Ethical Culture Society of New York, and a friend of Miss Holliday’s, delivered the eulogy. He said that Miss Holliday brought a fine intelligence to the theater and was a person who had integrity, grace, and a love for people.

“The public,” said Dr. Black, “will never forget her.”

A private Hebrew service was held later in Westchester Hills Cemetery with Rabbi Paul R. Siegel, of Temple Beth Abraham, of Tarrytown officiating.

In the obituary of Miss Holliday in the Herald Tribune, Max Gordon, the theatrical producer, and Max Gordon, the owner of the Village Vanguard mistakenly were assumed to be the same person.

The service ended with a performance of the adagio movement from the Mozart String Quintet in A Minor. A viola was added to the Guarnerius Quartet, says the New York Herald Tribune. After the service, members of the family and some friends went to the Westchester Hills Cemetery near Valhalla, N.Y. ♦