The following is an abridgement of a talk that Bill Gladstone gave to the Jewish Genealogical Society of Canada (Toronto) on March 28, 2012.

A landsmanshaft is a group consisting, at least initially, of Jewish immigrants who came from the same village, town, country or region in Eastern Europe or the Russian Empire. The word is Yiddish and means an organization of “landsmen” or “landsleit,” people from the same area with whom one naturally feels a special closeness while living in a foreign city such as Toronto.

The golden period of the landsmanshaft society extended from roughly 1900 to 1960. During this era, dozens of societies arose in Toronto. Examples include the Beizetchiner, Chenstochover, Driltzer, Ivansker, Kieltzer, Lagover, Linitzer, Mozirer, Ostrovtzer, Ozerover, Radomer and Warsaw-Lodzer societies in Toronto.

Their purpose and characteristics

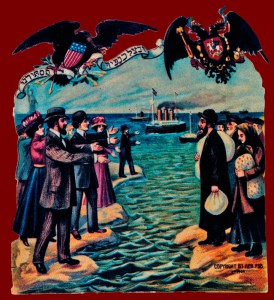

A central mandate of the landsmanshaft society was to help the members’ relatives and friends back in their town or region in the Old Country. Usually enormously thankful of their own good fortune in coming to Canada, many wanted to help their landsleit in the Old Country — relatives and strangers alike — to immigrate to Toronto, where they could live a much better life. Some societies were formed originally as “Hilfs Fareins,” geared to helping their brethren back home.

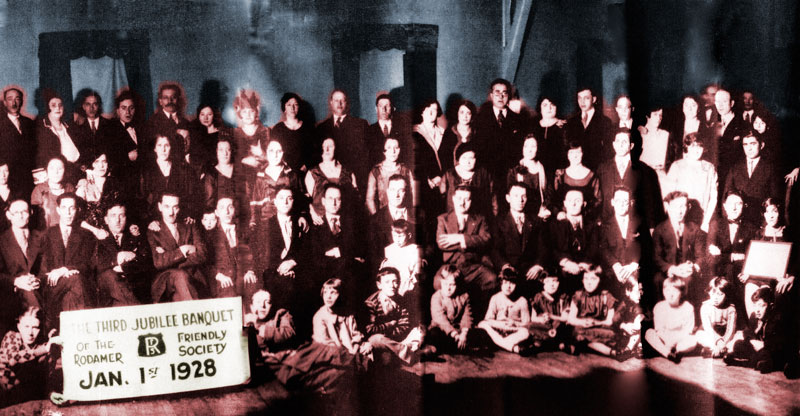

The societies provided an array of benefits to members. These usually included free loans, medical coverage, sick benefits, burial plots and spousal death benefits. There was also a strong social aspect to the societies, whose members met frequently for breakfasts, picnics, banquets and events in aid of philanthropical endeavours.

Some societies were religious and maintained a synagogue. “The majority of the synagogues in Toronto prior to the First World War and for many years afterwards were of the landsmanshaft type,” writes historian Stephen A. Speisman in his book, The Jews of Toronto: A History to 1937. Overlapping with the religious landsmanshaftn were the many “anshei”-type synagogues that arose in Toronto between 1900 and the 1930s.

Many societies looked back to the “Alte Haim” (old home across the ocean) for comfort. Others were so forward-looking that they adorned themselves with English names to hasten the process of oysgrinen zikh, ceasing to be greenhorns.

Harry Dworkin with group of immigrants from Kielce, Toronto, ca 1920. Photo from Stephen Speisman collection.

“As if to re-create in miniature the very world from which they had fled, the immigrant Jews established a remarkable network of societies called landsmanshaftn, probably the most spontaneous in character of all their institutions, and the closest in voice and spirit to the masses,” wrote Irving Howe in his seminal book, World of Our Fathers. “The landsmanshaft, a lodge made up of persons coming from the same town or district in the old country, was their ambiguous testimony to a past they knew to be wretched yet often felt to be sweet.”

Mutual benefit and other types of (Jewish) societies

Another type of organization, similar to the landsmanshaft and providing many of the same benefits, was the mutual benefit or benevolent society. These differed primarily because they did not have any geographical tag or association. Most established their own cemeteries and free loan societies.

Another type of society was the fraternal order, which was often ideological in tone — Zionist, socialist or communist. The Workmen’s Circle, the Jewish National Workers’ Alliance, the Labour League (which became the United Jewish Peoples Order or UJPO, and was communist) were essentially fraternal orders.

A fourth category were the local branches or lodges of non-sectarian fraternal orders: the Independent Order of Oddfellows, the Ancient Order of Foresters, the Canadian Order of Chosen Friends, and the B’nai Brith.

The demographer Louis Rosenberg published a thorough study of Toronto landsmanshaft and Jewish mutual benefit societies in 1945. He counted 39 societies in operation from 1896 to 1945 and attempted to categorize them by type. Rosenberg found that nearly half of those societies (18 out of 39) were of the landsmanshaft variety. There were probably more.

A list of Toronto-based landsmanshaft and mutual benefit societies appears here.

Earliest societies in Toronto

The story of the landsmanshaftn (plural for “landsmanshaft”) begins in the Pale of Settlement in the early 1880s, when a wave of antisemitic pogroms sparked the first mass migration of Jews to North America. A second, much larger wave of pograms began in 1903 and prompted a much larger mass migration of Jews across the Atlantic. (In Roumania, the migration began about 1899 or 1900, with the result that Roumanian Jews were often among the first to form landsmanshaftn in North American cities.)

The first known Jewish helping society here was the Toronto Hebrew Ladies Sick & Benevolent Society, established 1868 and renamed the Ladies Montefiore Hebrew Benevolent Society. It offered free loans, watchers for the sick (“bikur cholim”), funeral expenses, and support for bereaved families. It contributed to Sick Children’s Hospital, the Children’s Aid Society and other charities. It was affiliated with the Holy Blossom Congregation, and its methods of dispensing charity were considered very British and Victorian. Someone once remarked (as quoted by Speisman): “Every poor man is questioned like a criminal, is looked down upon; every unfortunate suffers self-degradation and shivers like a leaf, just as if he were standing before a Russian official.”

There were also two men’s lodges established in Toronto before 1900: the Canada Lodge of B’nai Brith, and Kesher shel Barzel. Both were local branches of American organizations. They were fraternal-type societies that offered some mutual aid benefits and did some philanthropic work. One of their main goals was to help “Americanize” the immigrant. In 1899, members of the growing Goel Tzedec Congregation established the Toronto Hebrew Ladies Aid Society.

After 1900

There were close to 3,000 Jews in Toronto by 1901, most affiliated with the English-speaking and well-assimilated Holy Blossom Congregation. A decade later, in 1911, the inner city was teeming with some 18,000 Jewish residents, mostly newly arrived, not wealthy, and not yet fluent in English. The city’s Jewish population would exceed 30,000 by the early 1920s. Thousands of arrivals each year needed food, clothing, shelter, jobs — and this is where the landsmanshaft and related societies excelled.

As in other cities, the early Jewish community in Toronto split along regional lines: Galicianers, Russians, Polish, Litvaks, etc., each with their own “anshei” type shul that may have also supported a Hilfs Farein or a Landsmanshaft society. “Anshei” type synagogues and shtiebls (storefront synagogues) proliferated after 1900. The anshei congregations were similar to the landsmanshaft societies and usually fulfilled some of the same functions. (“Anshei” is a Hebrew word, meaning “people of” — synagogues would typically be named Anshei Minsk, for example, meaning “people of Minsk.”)

Like most of the early anshei synagogues, the Austrian or Galicianer Shul, known as Shomrei Shabbos, was initially situated in the downtown neighbourhood of St. John’s Ward (“the Ward”). Its members brought over many relatives and landsleit, including the Orthodox religious leader, Rabbi Yosef Weinreb, known as the Galicianer Rebbe, who arrived about 1900 and would remain on the scene for more than 40 years. The Shomrei Shabbos Congregation split over an internal difficulty in 1906, and the separating faction built the Teraulay Street shul on what is now Bay Street. Numerous congregations sprung up throughout the Ward, which served as a first landing ground for Jewish immigrant families.

The Apter Society

The first Apter landsleit came to Toronto about 1900 and established the society about 1905; it began as a Hilfs Farein. Its members purchased a small synagogue on Centre Avenue near Dundas. A reminiscence in the Society’s 20th anniversary souvenir booklet in 1925 noted: “Especially in the winter, landsleit would come to warm themselves around the stove, have a cup of tea, find companionship and talk about the Old Country. Care was taken that the fire should not go out.”

The writer-politician Joseph B. Salsberg noted the “haimishe” atmosphere of what he called the “Apter Shteeble,” and said that it helped to fill many voids and provided a warm, hospitable haven for the lonely and unacclimatized immigrants.

“The Apter Shteeble was a tired frame cottage — one large room inside, devoid of all color or decoration,” Salsberg wrote in the Canadian Jewish News. “A simple wooden cupboard served as the ark that was draped with an unpretentious bit of cloth. A few salvaged wooden tables of grandmother’s kitchen variety, were scattered about. Only the centre table that served as a bima during the reading of the Torah had a covering cloth. A couple of dozen nondescript second-hand wooden kitchen chairs and a substantial, pot-bellied self-heater (pronounced ‘salifeter”) completed the furnishings.”

He continued: “What did those strangers to a bewildering new world talk about? It was mainly about the past; a past that now appeared blazingly coloured and attractive to them. They talked about their wives and children; about the Sabbath and holiday atmosphere ‘at home,’ in contrast with here; about the sacred dedication to learning Torah and they related wondrous tales of their respective Chassidic rabbis. They also expressed bitter disillusionment with ‘America,’ which meant all the Centre Avenues in all the cities of North America.

“Because of their uncompromising adherence to Orthodoxy, their work opportunities were severely restricted. So many of those in the group at the Apter Shteeble were obliged to become either rag pedlars or rag pickers in Jewish-owned ragshops. Their income was tragically small and they existed on a pittance in order to save a few dollars for the families they left behind. The evening’s conversation often led to conclusions they must go ‘back home’ (as soon as they save a few dollars) because ‘one can’t be a Jew here’ where the children were bound to grow up as ‘goyim.’”

As a peripheral observation, it seems relevant to note that the late Toronto artist Myer Kirshenblatt painted nostalgic, primitive scenes remembered from his childhood in Opatow (Apt) — scenes that also resemble the early primitive buildings on Centre Avenue in Toronto.

In 1918 the Apters moved to larger quarters at 216 Beverley Street. A relief committee raised funds for refugees of the First World War. They also raised funds during the Second World War. Like many societies, they were utterly transformed by the wave of refugees and survivors that reached Toronto after the Second World War. The newcomers didn’t feel entirely at home in the old Apter Society and so established a new one called the Apter Friendly Society. Both met on Beverley Street until a bitter controversy erupted between the factions and the building was sold. Thereafter the groups rented space at the Workmen’s Circle building on Lawrence Avenue West. The Apter Friendly Society is still active with a range of activities including going on visits to Poland.

Judean Benevolent and Friendly Society

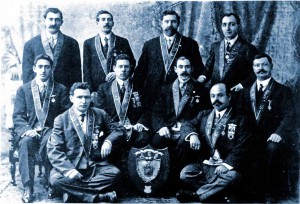

A good example of a fraternal and sick benefit society, this organization was founded by a group of English Jews in Toronto in 1905, initially as the Ancient Order of Foresters, with which it was affiliated until 1917; the Queen Esther Lodge for the wives was established 1910. After disassociating from the Foresters, the group was briefly part of the Grand Order of Israel before reincorporating as the Judeans in 1919.

According to their charter, their objects were to unite in bonds of fraternity all acceptable persons of good moral character, sound in body and health, and of Jewish faith and origin; to establish and maintain a fund for the relief of sick and distressed members who by reason of disease are unable to work; to provide members with funeral benefits and help during periods of mourning; and to provide medical services and medicine to members when necessary.

The Judeans had a bowling league, baseball team, and glee clubs. They organized socials, concerts, bridge tournaments, picnics at Hanlan’s point, and sent wartime relief packages to Europe and comfort boxes to soldiers.

Another local fraternal lodge, the Judaea Lodge of the Knights of Pythias, non-sectarian in nature, was a branch of an American organization started during the U.S. Civil War; established in Toronto 1927. It formerly occupied the building at Glen Park and Bathurst that is now the home of the Habonim Congregation.

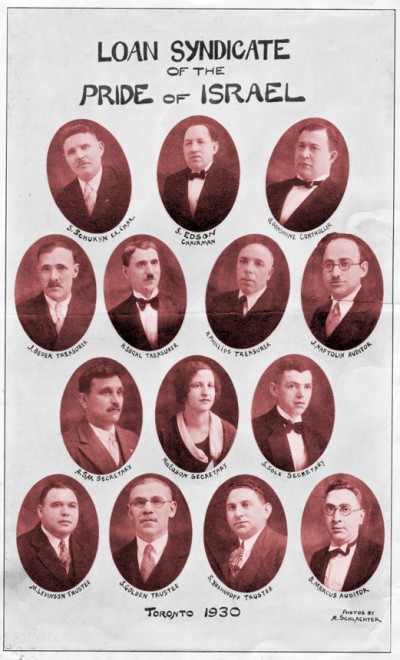

Pride of Israel

Founded 1905 in a cottage on Chestnut Street, the Pride of Israel Mutual Benefit Society became the largest and probably the most influential Jewish society in Toronto.

Shmuel Mayer Shapiro, editor and publisher of the Hebrew Journal and author of The Rise of the Toronto Jewish Community (published posthumously in 2011 by Now and Then Books), wrote that the Pride of Israel was a “Kol Yisroel” association where Jews from Poland, Russia, Roumania, Galicia, Latvia and other countries joined together for assistance and companionship. “This is what constituted its particular distinction and at the same time its broadness of scope,” Shapiro wrote. “The Society was not concerned with the ‘shtetl’ whose name it might bear, as was the case with other organizations. Its concern was directed equally towards its membership and the community at large . . . . When a member joined the Society all signs of his particular local origin in the Old Country were eliminated. He forgot he was a Russian, Polish, Galitzianer — he came to Canada as a Canadian and as a Jew.”

Shapiro noted as well that the Pride of Israel was one of few societies born in the pre-WWI era that did not have a Yiddish name; instead its name was “authentic Anglo-Saxon” and was merely transliterated phonetically into Yiddish characters. “We believe that the particular choice of name was not accidental or due to a whim; it was consciously and deliberately chosen by the founders as an open challenge flung to the landsmanshaften. They were convinced that the time had come for immigrants to Canadianize themselves rapidly and shed the extreme characteristics of the Old Country.”

According to Shapiro, the founders envisioned a merging of Jewish immigrant groups into a larger unity. “They were anxious for the immigrants to sink their regional differences and, regardless of their points of origin, acclimatize in the new surroundings and become Canadian citizens of Jewish origin rather than Yiddish speaking immigrants of East European origin. They wanted to build a new kind of landsmanshaft friendly society — a landsmanshaft without ‘landsleit’; a ‘friendly’ society in which it was not necessary to hail from a particular spot in Europe in order to qualify for admission. The only ‘passport’ needed in order to be eligible was a stout loyalty to one’s Jewish heritage and a willingness to respect in a positive way the environment.”

The Society hired its own “lodge doctor” as early as 1907; started a relief fund founded to help poor members; formed a bikur cholim committee to visit the sick; ran an Aktzia credit fund for free loans to members; and took a lead role in community activities. In 1908 it bought some farmland along Roselawn Avenue to provide burial plots for its members. In 1915 it supported the establishment of a Jewish butcher’s cooperative, hoping to attain lower meat prices. It also backed Jewish labour unions and helped to build the Brunswick Avenue Talmud Torah and other institutions. In the 1920s the Society would purchase blocks of 400 tickets for High Holiday services at the Goel Tzedec Synagogue; later it did the same for services held at the Brunswick Avenue Talmud Torah.

A Ladies Auxiliary was founded 1922 and thenceforth members brought their wives to meetings. The women independently held lectures and entertainments of various sorts to raise funds for charity. Wives of the founding members funded the old Jewish medical dispensary on Simcoe Street, the Mount Sinai Hospital on Yorkville Avenue, the Folks Farein, United Jewish Welfare Fund and the Jewish Old Folks Home on Cecil Street.

The Society was known for its compassionate approach to charity. During WWI, the society heard of a family whose breadwinner had suddenly died. He was a non-member, but nevertheless the society gave the widow $1,000. During the Second World War, members sent thousands of parcels to the armed forces. They also held blood drives for the wounded, collected pairs of shoes for the barefooted, raised funds for ambulances and much more.

Like other societies, Pride of Israel raised money for victims of the Nazis during the war and assisted the wave of Holocaust survivors that came here afterwards. In 1950 it purchased its own building on Spadina Avenue for use as a meeting hall and a synagogue. Today the synagogue, now along north Bathurst Street, is the most visible remnant of the former mutual benefit society.

The Mozirer Sick Benefit Society was also founded in 1905, but was not restricted to people from the same town (Mozyr). Like the Pride of Israel, the Mozirer offered sick and death benefits but was not religious.

Agudas Hamishpocha

A landsmanshaft-type society, the Agudas Hamishpocha was founded for members of the extended Rubinoff and Naftolin families in 1928. The Society had a hall on College Street, then another on Wilson Avenue, which it sold in the 1980s, establishing a philanthropic fund with the proceeds. Children and grandchildren of the original members still meet (in 2012) for breakfasts six times a year. According to the late Stephen Speisman, this was the only family-based landsmanshaft society in Toronto.

Lazar Rotenberg and the Ivanskers

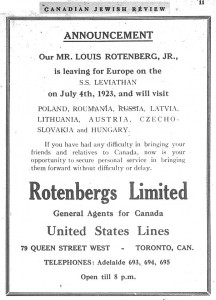

Ivanskers were supposedly among the earliest Polish Jewish arrivals in Toronto. One of the earliest was businessman Lazar Rotenberg, who opened a travel agency and helped to bring hundreds of Ivanskers to Toronto. Many of them found work in his factory. Many Jews in Toronto sent money, packages and ships’ tickets back to the Old Country with the aid of his steamship ticket agency, located on Queen Street near York.

When Rotenberg died in 1936, his obituary related the following: “He wrote to his friends and acquaintances, he sent them steamship tickets, and he befriended them in his house when they first arrived to a strange land. For many years he was the leader and the patriarch of the Ivansk Jews. They came to him with their troubles and with their joys, and presented themselves on all important occasions.”

The Rotenberg ledger, which is viewable online on the website of the Jewish Genealogical Society of Canada (Toronto), is a valuable genealogical resource especially for researchers with families from Ivansk.

The Rotenberg ledger, which is viewable online on the website of the Jewish Genealogical Society of Canada (Toronto), is a valuable genealogical resource especially for researchers with families from Ivansk.

Despite their early presence here, it wasn’t until 1932 that the Ivanskers established a mutual benefit society; they also opened a shul at College and Bathurst. According to an essay in the Society’s 25th anniversary booklet (1957), members felt a powerful nostalgia: “We Ivansker feel the attachment to our old home perhaps more than other landsmanshaftn. The indelible mark of Ivansk is quite noticeable in all our activities. We feel a love and devotion to the town of our birth — and perhaps we find it more difficult than others to become acclimatized to the routine-like, prosaic nature of life on this side.”

The Ivanskers were reportedly the first in Toronto to erect a Holocaust monument (in Bathurst Lawn cemetery in 1951). Today it is still a healthy and vibrant organization. “At this time many landsmen societies in Toronto are closing and transferring their assets to the Jewish Federation,” its website proclaims. “The Ivansker Society is financially solvent and remains active with over 150 members, still holds to principals that we serve as a burial society; gives to charities in Israel and Canada; provides communal focus for members to share Yiddishkeit and shared Ivansk heritage.”

The Chenstochover Aid Society began as a Hilfs Farein in 1914; eventually drafted a constitution, provided mutual and sick benefits, established an Aktzia loan society, and purchased cemetery grounds. They helped bring over war orphans from Ukraine in the 1920s; raised funds for Palestine Jews, youth aliyah, and the Israel Histadrut campaign during the war. Like the Apters, they were revitalized after the war by an influx of Holocaust survivors.

Like many societies, only men were admitted as members in the early years. In 1999 the wives of members were allowed and the membership doubled. Today the Society thrives, with about 150 members who meet three or four times each year; the meetings include an annual yahrzeit ceremony and a separate visit to the cemetery. The Society raises money for the local Jewish community and for Israel. And perhaps most important for its future, it has succeeded in attracting younger members (“young” is here defined as being between 50 and 70 years of age), partly due to the plain and simple incentive of burial plots. But a connection to Chenstochover is still a necessity.

Kielcer Sick Benefit Society

Founded 1912, the Kielcers had a synagogue on Dundas Street at Huron. Its longtime president was Aaron Ladovsky, founder also of the bakers union and the famous United Bakers Dairy Restaurant, which marks its centennial in 2012. Ladovsky and his wife, Sarah, welcomed countless immigrants to the city and helped them get their start.

Founded 1912, the Kielcers had a synagogue on Dundas Street at Huron. Its longtime president was Aaron Ladovsky, founder also of the bakers union and the famous United Bakers Dairy Restaurant, which marks its centennial in 2012. Ladovsky and his wife, Sarah, welcomed countless immigrants to the city and helped them get their start.

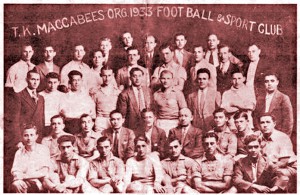

A 1933 photo of the Kielcer Maccabees football and sports club shows the diverse role that landsmanshaft played. Jewish athletic teams, many derived from these societies, would play baseball and other sports with other community teams in local parks. The current Kielcer Congregation on Bathurst Street at Shelborne may not

have any connection to the original Society beyond the name.

The Kielcer Ladies Auxiliary was one of numerous ladies auxiliaries closely affiliated with the landsmanshaft societies that played a key role in community affairs. Many of the ladies joined forces with the Ezras Noshem Society, a charity founded in 1913 whose volunteers were entirely working-class women.

The volunteers took kosher food daily to a 96-year-old Jewish woman at the Home for Incurables on Don Avenue, who prayed that she might die in a Jewish environment. Based on this case, the Society held a meeting at 20 Grange Avenue and decided to form the Old Folks Home which was established on Cecil Street. They raised money to purchase the building, and the old woman was transferred to the home, where she died at the age of 100.

Stephen Speisman photographs

In the 1960s, Stephen Speisman photographed many Jewish landmarks around Toronto, including various headquarters and former homes of anshei congregations such as the Anshei Slipia Beit HaKnesset (founded 1908), the Anshei Drildz (1934) and the Husiatner Klauz, a small synagogue on Brunswick Avenue (date of origin unknown). Another was the Anshei Lubavitch Synagogue at Denison and Grange, which actually had little to do with the Ukrainian town of Lubavitch except that its members adopted the Hassidic denomination of Judaism associated with that town. Similarly, the Husiatner Klauz followed the teachings of the Husiatner Rebbe and its members did not necessarily come from that Ukrainian-Hungarian town.

Declining memberships, mergers and legal tussles

Over the years many societies have faced the problem of declining memberships. Occasionally some societies seek to solve the problem through a merger with another society, a process that can be fraught with risk. J B. Salsberg once wrote a comic tale about two mythological groups, the Hotzeh Society and the Plotzeh Society, both struggling with diminishing membership and considering a merger as a means to save themselves.

“The negotiations were long, critical and with frequent breaks,” Salsberg wrote. “Hotzeh, because it was older and had a bigger treasury, wanted Plotzeh to join and become part of Hotzeh. But Plotzeh, on the other hand, argued that Hotzeh may be older and may have a bigger treasury but Plotzeh had more members and twice the number of burial plots in its cemetery. Therefore Hotzeh should join Plotzeh.

“Negotiations were stalemated after one of the Plotzeh negotiators suffered a mild heart attack during the arguments. Eventually wisdom prevailed and it was agreed that the merged society should be called the Hotzeh-Plotzeh Society.

“Another month was lost on the question of which of the present two presidents should be the president of the merged society. Finally, it was agreed that for the first year there be two co-presidents, a Hotzehr and a Plotzehr. The merger was celebrated at a gala ‘merger banquet’ of the new Hotzeh Plotzeh Society that left the merged treasury with gaping holes. But it was freilich.”

An article that appeared in the Financial Post in 1933 described a “run” on an Aktzia or Hebrew Free Loan Society based in Toronto, just as in a bank. Depositors of the landmanshaft’s fund had invested on margin, apparently, and the money had been loaned out at a small rate of interest. There was a panic, resulting in the voluntary liquidation of the fund.

The battle of Brunswick Avenue

The battle of Brunswick Avenue

The First Naraveyer Congregation was formed about 1914 as a landsmanshaft-type synagogue for former residents of the Galician town of Narayev. Legend has it that a group in New York was also planning to found a congregation and the Toronto Narayevers rushed to do it first, hence the name.

In the early years, the congregation employed a “lodge doctor” to look after the medical needs of its members. It was said that congregants kept in very close touch with their relatives back home, so much so that “when someone’s cow died, the Toronto group sent money over to buy a new one.” Eventually, however, Anshei Narayev devolved into just a synagogue.

In 1940 the Narayevers moved from Huron and Dundas to the building on Brunswick Avenue where it is still located. Over time the synagogue lost most of its regulars. In the 1980s a group of modern orthodox young people arrived, renovated the downstairs and established an egalitarian but otherwise Orthodox congregation there. Former Canadian Jewish Congress executive Ben Kayfetz once wrote an article, “The Battle of Brunswick Avenue,” recounting that some of the regulars were so displeased that they took legal action.

“As Abraham Lincoln put it,” Kayfetz wrote, “a nation cannot survive half-slave and half-free, and five members of the Narayever Congregation applied to the courts to have the auxiliary congregation declared illegal.” A Supreme Court judge ultimately allowed the egalitarian congregation to stay. Afterwards the oldtimers dispersed and the egalitarians moved upstairs, thus beginning a new chapter in the life of the Narayever. According to its own website, it is now one of the best attended and most active synagogues in the downtown area.

UJA Federation’s Societies Division

UJA Federation’s Societies Division

Six years ago, in 2006, the UJA Federation of Greater Toronto established a Societies Division and invited the Toronto societies to contribute to a philanthropical fund. So far 13 societies have done so, building up an endowment fund of nearly $1 million. Contributions have come from the Stopnitzer Young Mens Benevolent Association, Zagliember Ladies Auxiliary, Agudas Hamishpocha, Chenstochover Aid Society, Chmielnicker Society, Drildzers, Farband of Lithuanian Jews and the Masada Chapter, Kielcer Sick Benefit Society, Lagover Society, New Fraternal Jewish Association, Ostrovtzer Independent Mutual Benefit Society and the Wierzbniker Society.

Many of these societies have contributed funds towards a “Bridge of Hope,” that will connect the Lipa Green Building to the Prosserman JCC and be the main entranceway to a new proposed Holocaust Museum. The bridge will have images of different towns of Poland from before the war, with touch-screen facilities for learning. Tens of thousands of students are expected to cross the bridge to visit the Museum each year.

Conclusion

The primary role of the landsmanshaft and mutual benefit societies of Toronto has changed dramatically over the last century. As far as their original purpose goes, they have become outdated and anachronistic. Many have not survived into modern times. But some, at least, have adapted well to modern times and have involved the younger generation to ensure a continuity into tomorrow. ♦

© 2012 by Bill Gladstone. All rights reserved.