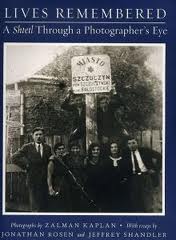

The collected photographs of Zalman Kaplan, who ran a studio in the town of Szczuczyn, Poland between 1898 and 1939, might never have been considered remarkable or been made the focus of a traveling museum exhibit, had it not been for the almost complete destruction of Szczuczyn’s Jewish community of 3,000 souls during the Nazi era.

The collected photographs of Zalman Kaplan, who ran a studio in the town of Szczuczyn, Poland between 1898 and 1939, might never have been considered remarkable or been made the focus of a traveling museum exhibit, had it not been for the almost complete destruction of Szczuczyn’s Jewish community of 3,000 souls during the Nazi era.

His carefully posed and composed photographs — some 200 of which form the basis of “Lives Remembered: Photographs of a Small Town in Poland, 1898 to 1939,” currently on view at the Beth Tzedec Synagogue — seem to reveal a prosperous town whose well-kept Jewish citizens were happily involved in a range of middle-class activities, including playing volleyball, listening to phonograph records, riding bicycles and driving automobiles.

Kaplan’s various group photos record the vibrant everyday life of Szczuczyn Jews at home and school, on nature outings, in military uniform and at synagogue. But as the photographer’s grandson Mike Marvins points out, they do not show the poor yeshiva bochers, squalid marketplaces or streimel-wearing old rebbes typical of the photographs of Roman Vishniac, who captured the more romantic, Old-World elements of Polish Jewry.

“Vishniac’s pictures are mostly of impoverished people and mostly Hassidic people, but my grandfather’s pictures show ordinary, everyday people,” said Marvins, himself an accomplished Houston-based photographer who put the show together and attended its Toronto opening.

Toronto, it turns out, has played a significant role in Marvins’ family history and in the genesis of the exhibition, which was created for the New York Museum of Jewish Heritage more than a decade ago. (It has traveled to various American cities and the Jewish Historical Institute of Warsaw, Poland, and a version of it is currently touring Poland; several of the photographs also appeared in an earlier exhibit at Beth Tzedec.)

Kaye Marvins, the photographer’s son, came to Toronto in the 1920s as Moishe Kaplan and worked briefly for the Gilbert photography studio on Queen Street West before relocating to Boston and then Houston.

Recollecting that Marvins used to babysit for him when he was a child, local photographer Al Gilbert noted that Zalman Kaplan, who died in 1941, had once expressed a wish to cross the Atlantic. “When he first got a Leica camera — that was the Rolls Royce of cameras — his comment was, ‘If I could just take this camera to America, I would be a wealthy man,’” Gilbert said.

Recollecting that Marvins used to babysit for him when he was a child, local photographer Al Gilbert noted that Zalman Kaplan, who died in 1941, had once expressed a wish to cross the Atlantic. “When he first got a Leica camera — that was the Rolls Royce of cameras — his comment was, ‘If I could just take this camera to America, I would be a wealthy man,’” Gilbert said.

Another Kaplan son settled in Toronto permanently. Laura Kaplan Silver is a retired Toronto-area teacher and a granddaughter of the photographer who helped her Houston cousin assemble the exhibition.

A photograph captioned “Kelsen leaves for Canada,” showing several people at a table, suggests that other Szczuczyners also reached these shores. Indeed, some Kelsen family members attended the opening and proudly pointed out their respective fathers, Max and Haim Kelsen, as boys in a blown-up photograph of a group of costumed children acting in a Purim shpiel. Both are wearing fake moustaches as they stand amidst the colourful group. Max became a cigar store proprietor in Toronto, Haim a manufacturer.

Ellen Scheinberg, director of the Ontario Jewish Archives, also took a personal interest in the exhibit, explaining that her paternal ancestors lived in Szczuczyn but left for New York before 1914. “It’s a really impressive exhibit,” she said. “It gives you a good sense of the community before the Nazis tore it apart.”

In the mid-1990s, Marvins and Silver pooled their private collections of their grandfather’s photographs and realized they could mount a poignant exhibit of the town’s Jewish community if they could find more samples of his work.

“I looked up the town of Szczuszyn on the internet site Jewish-Gen and found that about 70 people were researching that town,” Marvins recalled. “I put out a group e-mail explaining that I was looking for old pictures, and before we turned off the computer that night we started getting replies — from Europe, from Australia, from the United States, from Israel.”

Eventually they collected more than 800 of their grandfather’s photographs, more than enough for a first exhibition in 2002. “I keep getting pictures,” Marvins said. “I just got a new picture last week.” ♦

© 2006