Four years ago, a Pennsylvanian antiques collector purchased a trove of old scrapbooks and photo albums at an estate sale in the town of Red Lion, Pa. The cache, which included hundreds of photographs including some taken in the Warsaw Ghetto between 1940 and 1943, cost only $10.

Four years ago, a Pennsylvanian antiques collector purchased a trove of old scrapbooks and photo albums at an estate sale in the town of Red Lion, Pa. The cache, which included hundreds of photographs including some taken in the Warsaw Ghetto between 1940 and 1943, cost only $10.

Discovering that the material was related to a local woman formerly known as Mary Berg, who had died some months earlier, the collector put the whole lot up for sale at Doyle’s, a local auction house. But then relatives of Mary Berg heard of the sale and, along with several Judaic scholars and curators, convinced Doyle’s to cancel it, asserting that the material belonged in a Holocaust museum rather than in private hands.

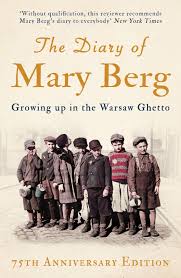

That episode served as an apt postscript to Mary Berg’s life, for she was a woman who sought fervently to avoid the public spotlight in her adult life, yet it found her anyhow after her death at the age of 88. It turns out that Berg was perhaps the most impressive and talented child diarist of the Holocaust after the much-more-famous Anne Frank. After the war her Polish diaries were translated into Yiddish and English and published as Warsaw Ghetto: A Diary in the United States in February 1945 to wide acclaim. (This year, a 75th anniversary edition was published under the title, The Diary of Mary Berg: Growing Up in the Warsaw Ghetto.)

A survivor of the Warsaw Ghetto, Berg was born as Mary Wattenberg in Lodz on April 20, 1924, but changed her birthday to October 10 after the Germans made it illegal for a Jew to share the same birthdate as Adolf Hitler. Only fifteen years old when the Nazis marched into Poland, she brought an astonishingly mature perspective to the wartime diary that she kept faithfully to document Jewish life and suffering in the increasingly overcrowded and disease-ridden ghetto. As the child of an American-born mother, she and her family held American citizenship and were given more food, better living quarters and other privileges that ultimately saved their lives. Her protected status allowed her to become a fearless eyewitness of the encroaching horrors she saw all around her.

Like many sensitive diarists living through an historic ordeal, Berg reported the latest details of the ghetto residents’ suffering with authority, matter-of-factness, immediacy and detachment. “The ghetto has been isolated for a whole week,” she wrote on November 22, 1940. “The red-brick walls at the end of the ghetto streets have grown considerably higher. Our miserable settlement hums like a beehive. In the homes and in the courtyards, wherever the ears of the Gestapo do not reach, people nervously discuss the Nazis’ real aims in isolating the Jewish quarter. How shall we get provisions? Who will maintain order? Perhaps it will really be better, and perhaps we will be left in peace?”

Like many sensitive diarists living through an historic ordeal, Berg reported the latest details of the ghetto residents’ suffering with authority, matter-of-factness, immediacy and detachment. “The ghetto has been isolated for a whole week,” she wrote on November 22, 1940. “The red-brick walls at the end of the ghetto streets have grown considerably higher. Our miserable settlement hums like a beehive. In the homes and in the courtyards, wherever the ears of the Gestapo do not reach, people nervously discuss the Nazis’ real aims in isolating the Jewish quarter. How shall we get provisions? Who will maintain order? Perhaps it will really be better, and perhaps we will be left in peace?”

Hard to believe that such mature observations sprang from the pen of a fifteen-year old. Like Anne Frank, Mary Berg also wrote with a distinctive literary sensibility, even when describing intensely painful scenes that she witnessed.

“Through a show window in a store I can see the reflections of various people. The spectacle is now familiar to me: a poor man enters to buy a quarter of a pound of bread and walks out. In the street he impatiently wrenches a piece off the gluey mass and puts it in his mouth. An expression of contentment spreads over his entire face, and in a moment the whole lump of bread has disappeared. Now his face expresses disappointment. He rummages in his pocket and draws out his last copper coins . . . not enough to buy anything. All he can do now is lie down in the snow and wait for death.”

“Through a show window in a store I can see the reflections of various people. The spectacle is now familiar to me: a poor man enters to buy a quarter of a pound of bread and walks out. In the street he impatiently wrenches a piece off the gluey mass and puts it in his mouth. An expression of contentment spreads over his entire face, and in a moment the whole lump of bread has disappeared. Now his face expresses disappointment. He rummages in his pocket and draws out his last copper coins . . . not enough to buy anything. All he can do now is lie down in the snow and wait for death.”

Berg’s book fell out of print in the early 1950s, just around the time the first edition of Frank’s diary appeared in 1952; the latter has been continuously in print ever since. For some reason, as Holocaust scholar Alexander Zapruder has observed, Berg’s diary “didn’t have that same lasting hold on the public imagination” that Anne Frank’s diary did.

As scholar Lawrence Langer has noted, Berg focused mostly on the deprivations and atrocities she had witnessed, whereas Frank focused mostly on her own emotional development and idealistic dreams while living with her family and others in a cramped hiding space. “Anne Frank’s diary was and is more popular because it records no horrors; the horrors came after she stopped writing, so readers don’t have to confront anything painful,” Langer observed.

Part of the reason for the relatively obscurity of Mary Berg’s published diary must also lie with the author herself. When she first arrived in the United States in 1945, Berg was eager to get her diary into print, but she later distanced herself from it, sought anonymity instead of celebrity, and even seemed opposed to continued attention to the Holocaust when there were subsequent genocides still unfolding around the world. In the early 2000s she told a professor who wanted to bring out a new edition of her book to “get a life . . . there were other things happening in the world,” the New York Times reported.

For those who visit Warsaw today, there are only scant relics left of the Warsaw Ghetto: a few buildings and sections of wall, various markers and monuments, the Nozyk Synagogue, and the Umschlagplatz from which more than 300,000 Jews were deported to Trebinka and Majdanek (nearly 100,000 others died within the ghetto walls). There is also a museum devoted to the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. By some miracle, Warsaw’s huge Jewish cemetery is also extant, along with its antiquated sewer system through which ghetto Jews used to smuggle in food, weapons and other commodities from outside.

The Diary of Mary Berg: Growing Up in the Warsaw Ghetto is, therefore, one of the most articulate relics of all. It is history that neither accentuates, nor shies from describing, the repeated cruelties of the Germans towards the usually defenseless ghetto residents. Berg often understated the tragic events she witnessed, exhibiting an obdurate mental calmness in what can only have been the most stressful of living conditions.

For example, after she dispassionately describes the German shooting of 110 persons in the Gesia Street prison in June 1942, she wrote these sentences to conclude her description of the cold-blooded execution: “The victims went to their death in complete calm. Some even refused to be blindfolded. Among the victims there were several women, two of them pregnant. After this crime had been perpetrated in front of witnesses, Pinkiert’s funeral carts took the bodies to the Jewish cemetery. There is general mourning in the ghetto.” ♦