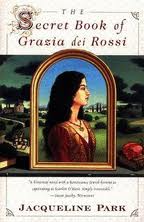

After a distinguished career as a television scriptwriter and a professor of dramatic writing, Winnipeg-born Jacqueline Park, at 72, has achieved every writer’s dream: an acclaimed and commercially successful first novel. The book, a sweeping historical epic of the Italian Renaissance, is called The Secret Book of Grazia dei Rossi. Published by the prestigious American publishing house Simon & Schuster, it won wide critical acclaim; one reviewer called it “a Sistine Chapel of a novel, larger than life, richly conceived, and majestic in its exaltation of humanity.” German publication rights were recently sold for $400,000.

After a distinguished career as a television scriptwriter and a professor of dramatic writing, Winnipeg-born Jacqueline Park, at 72, has achieved every writer’s dream: an acclaimed and commercially successful first novel. The book, a sweeping historical epic of the Italian Renaissance, is called The Secret Book of Grazia dei Rossi. Published by the prestigious American publishing house Simon & Schuster, it won wide critical acclaim; one reviewer called it “a Sistine Chapel of a novel, larger than life, richly conceived, and majestic in its exaltation of humanity.” German publication rights were recently sold for $400,000.

For Park, who readily admits she is not a historian, this latest chapter in her life started a decade ago when she realized that, as a faculty member of New York University, she could take courses for free. She admits she knew next to nothing about art history or the Italian Renaissance when she first enrolled in courses on those subjects. Yet now she says her 570-page book — reduced dramatically from a manuscript of about 1,400 pages, which would have made it longer than Gone With The Wind — is nothing if not historically accurate.

“This story is about events that actually happened,” Park explains to this journalist after giving a well-attended reading in the Toronto megabookstore, Indigo. “I don’t think a Renaissance historian would find much to take issue with. The battles did take place in the places and times described, and the descriptions of the buildings were from my own observations and from contemporary sources.”

Park went to Italy almost yearly during her ten years of research, explaining that she couldn’t write about the period and its inspiring architecture until she saw “the way the light falls on these buildings.”

During the Renaissance, many Italian aristocrats and merchants kept secret books (“libri segreti”) in which they kept accounts of their mercantile dealings for the edification of their children. Park’s book is styled as a secret book in which Grazia dei Rossi, a Jewish secretary to the aristocratic lady Isabella d’Este, unpours the secrets of her heart to her son. Dei Rossi tells of her failed attempt to marry a Christian prince and her subsequent marriage to an esteemed Jewish physician. She describes many startling episodes of Renaissance life, including military battles and an anti-Jewish pogrom. She paints the court of Isabella d’Este, a well-known historical figure, with a rich level of vividness and detail, bringing it fully to life.

Park says she got the idea for the novel after finding a pair of letters in the New York Public Library from the actual Isabella d’Este to a Jewish woman, encouraging her to convert to Christianity. “Those letters gave me a feeling I was on solid ground,” she says. “I had a story and the beginning of a conflict with this woman. It gave me the confidence to write about this period.”

Park, who still has family in Winnipeg and Toronto, divides her life between Toronto, New York and Miami. While writing her book she was a regular at the New York Public Library for years.

“Most of my research was just an attempt to get a grip on what everyday life was like. That’s the hardest thing to find out. I spent literally years with all my contacts in Rome, trying to find out how many kitchens there were in the Colona Palace in the period I was writing about. Four hundred people lived in that palace. Did they all eat together, or was there some kind of hierarchical arrangement? How many kitchens were there? It’s very hard for me to write about people with assurance when I feel I don’t have enough details of everyday life.”

As energetic as she is accomplished, Park is diminutive, graceful and easy to talk to. She has come a long way from her Winnipeg roots, but it was clear from early on that she was bound for great things. As a teenager, she became a local singing sensation with her partner, Monty Hall of Let’s Make A Deal fame. When she was 19, John Grierson, the legendary filmmaker of National Film Board, offered her a job — “and by some miracle my parents let me go, so I learned how to make movies.” Specifically, during the war years, she made films extolling the virtues of war bonds. “Because I had acquired a degree in economics, it was thought I could handle the information from the Dominion Bureau of Statistics and put it into pictorial form to educate people,” she explains.

After the war, she earned an advanced degree from the University of Toronto, where she studied with the extraordinary scholar Harold Innis, and married and raised a family. She also began writing scripts at the CBC for productions that occasionally went into U.S. syndication. Eventually she hired a U.S. agent and got hired to write a series of documentaries for the Ford Foundation. She moved to New York one year and never looked back. In 1968 she joined the staff of New York University, and became professor emeritus two years ago.

Harboring plans to write two more books, Park admits that her literary success has been tinged with sadness. Her husband of 36 years, who was a pillar of support throughout the creative process, died two years ago, before the book was published.

The youthful-looking Park says she has no desire to act her age. People often express disbelief about her age, she says. “Remember what Gloria Steinem answered when someone told her she didn’t look 60? She said, ‘This is what 60 looks like.’ When people tell me I don’t look 72, I say, ‘Yes, I do. This is what 72 looks like.’

“You don’t have to sit back in your easy chair, just because your parents did,” she says. “I have a strong feeling about that.” ♦

© 1998