by Ben Lappin (from Commentary, 1955)

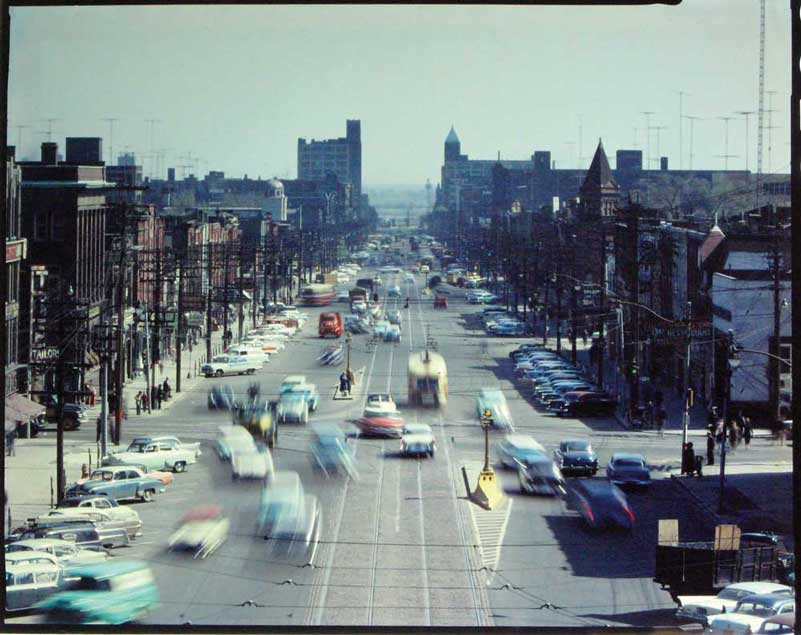

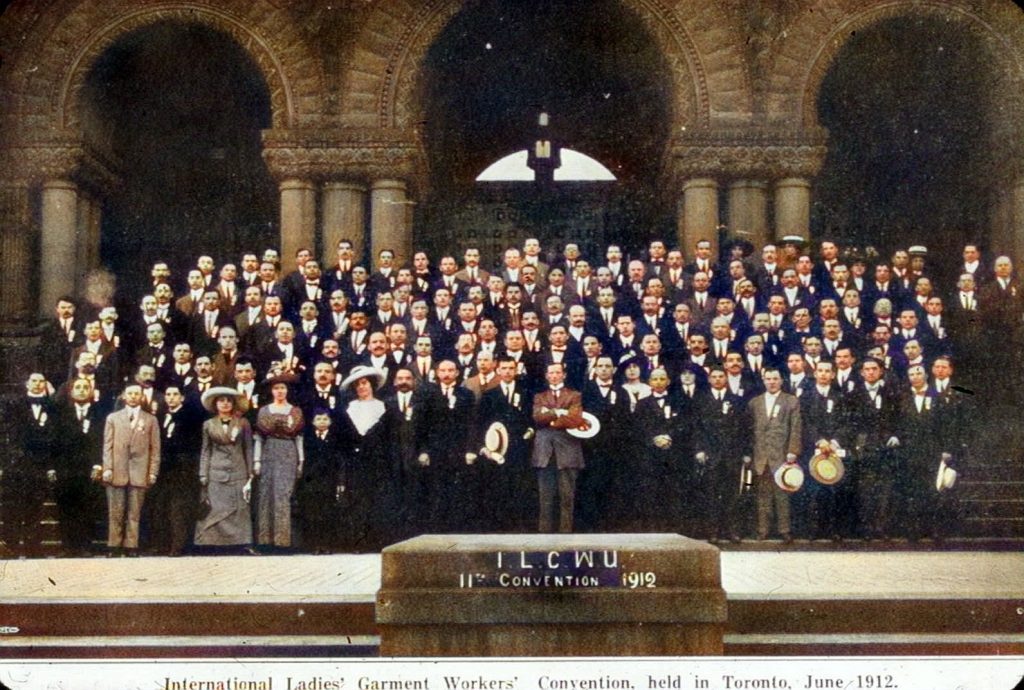

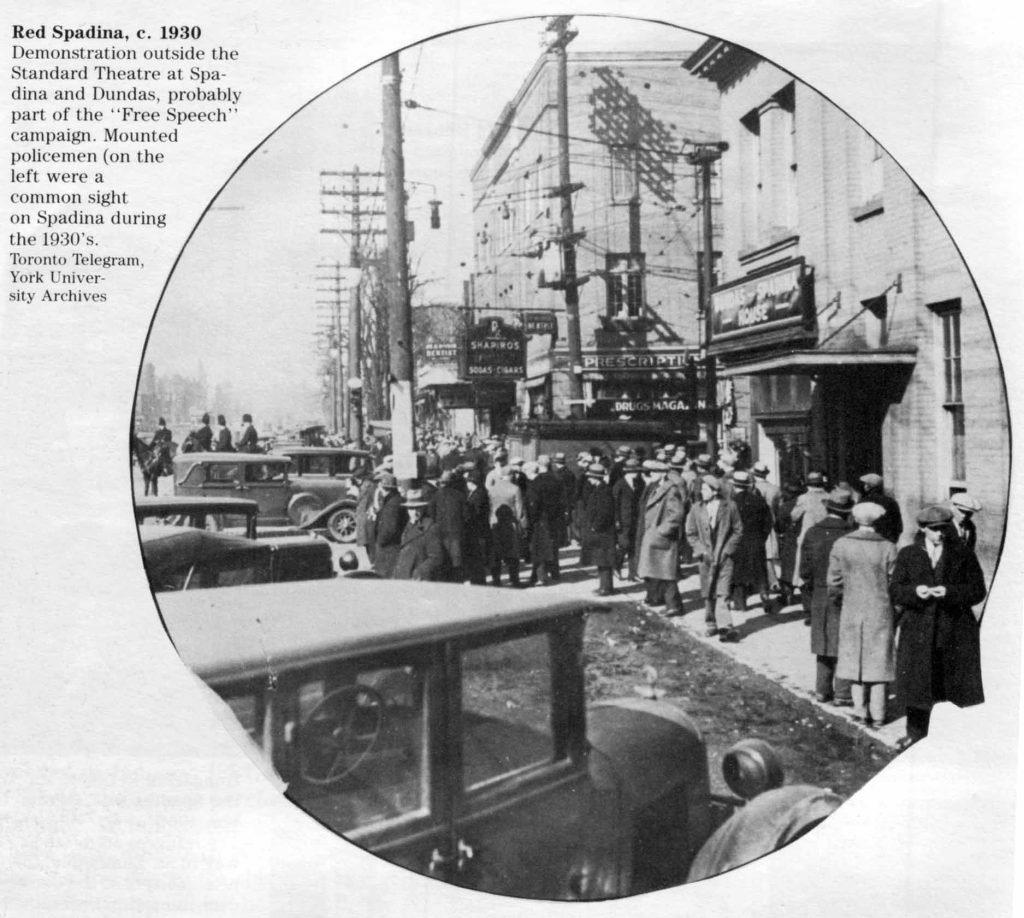

Spadina Avenue, the main street of the needle trades in Toronto, looks very much the same as it did ten, twenty, thirty years ago. The same kind of old-fashioned haggling still goes on between the employers and the handful of tense harassed business agents – former pressers, operators, and finishers – who guard the interests of Toronto’s twelve thousand needle workers. And there is the same vigorous thumping on the cutting table when union agreements come up for renewal – to such good effect that wages and working conditions have been maintained despite the flooding of the labor market by the tide of job-hungry post-World War Two refugees. There has been one change, however.

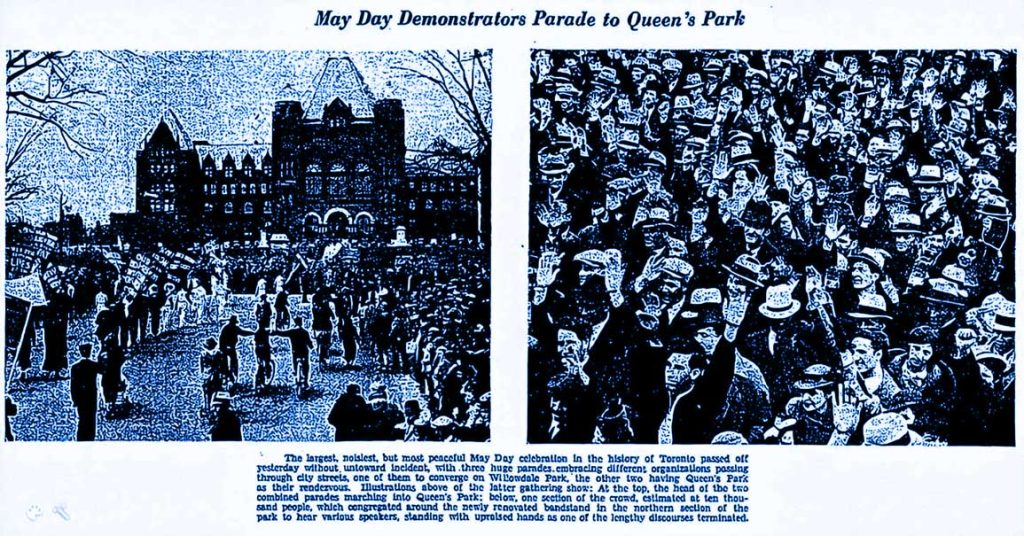

May Day, which before World War Two was a mandatory holiday in every needle-trade union contract, has disappeared together with the parades that used to tie up Toronto’s downtown traffic for an entire morning. This was no idle fanfare, but a demonstration of real militancy, and any needle-trade worker caught in a factory on the first day of May Day was fined by the union fifteen dollars on the spot.

Ask any of the union men (as I did) what happened to May Day and you get a kind of standard bellicose answer. “In case you think the bosses had anything to do with it, you’re wrong, my friend,” said the business agent of one of the large locals eyeing me as though I had no business remembering that far back. “It’s just that we got mixed up with the wrong crowd. First, it was the Communists, and as if that wasn’t enough we had the Nazis on our hands too. They declared May Day a National Socialist holiday, and sent their storm troopers out on parades. When Stalin and Hitler signed the pact we decided we’d had enough. The whole thing had become a bad joke.” Then he added quickly, “The parade business I mean. The real spirit of the day, no amount of phonies can squelch. You come around here tonight and you’ll see a real meeting, a small meeting maybe, but you’ll find out what May Day really stands for.”

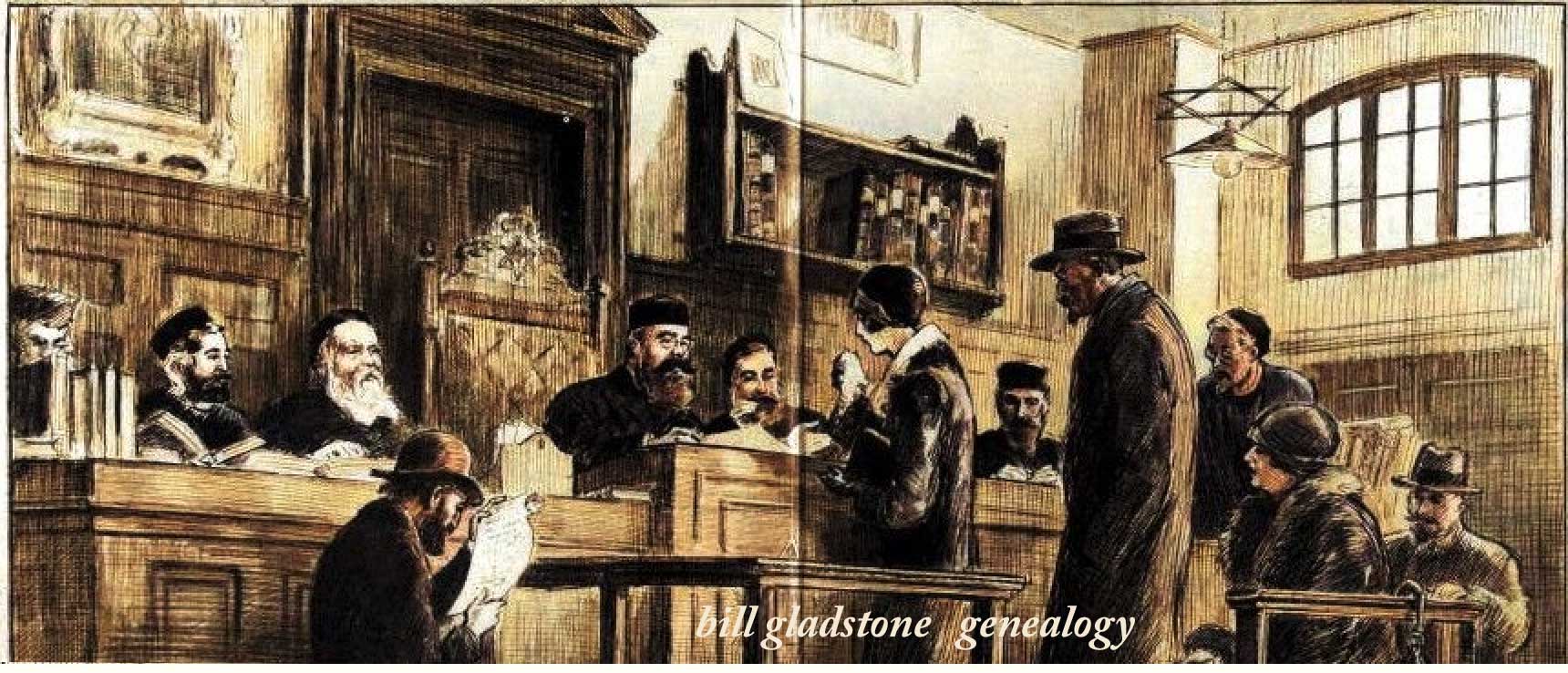

I took his advice and came back the same evening to the Labor Lyceum, an old brick building which houses the needle-trade unions in Toronto. The fifty-odd men and women in the room were mostly middle-aged, long associated with the arbeiter kreisn, with labor circles. There was a quiet, studious quality about the group as if it had come together for a lecture rather than for a May Day feierung as the poster on the door of the Labor Lyceum proclaimed. The chairman added to this impression with his patient manner and his cultured Russian Yiddish. With a touch of wistful humour he welcomed the massn. In a more serious vein, he went on to assure the assemblage that dwindling numbers did not matter so long as there remained a core of determined people prepared to carry forward the meaning of May Day.

I took his advice and came back the same evening to the Labor Lyceum, an old brick building which houses the needle-trade unions in Toronto. The fifty-odd men and women in the room were mostly middle-aged, long associated with the arbeiter kreisn, with labor circles. There was a quiet, studious quality about the group as if it had come together for a lecture rather than for a May Day feierung as the poster on the door of the Labor Lyceum proclaimed. The chairman added to this impression with his patient manner and his cultured Russian Yiddish. With a touch of wistful humour he welcomed the massn. In a more serious vein, he went on to assure the assemblage that dwindling numbers did not matter so long as there remained a core of determined people prepared to carry forward the meaning of May Day.

He presented the first participant of the evening, an actor who had once been a minor member of the famous Vilner Trupe, but now makes a bare livelihood the year round through such odd jobs as camp directing, announcing chores on the Yiddish Hour, and producing an occasional shule concert. He launched out on a reading of Peretz’s “Amol Iz Geven a Malach” (Once There Was an Angel). This dramatic recital, about a band of early revolutionaries ambushed by Cossacks in the midst of an illegal May Day celebration, was rendered with restraint but with intense artistry well attuned to the small, intimate audience. The artist beamed as he sat down and acknowledged the warm applause from his seat without getting up.

The chairman waited for the acclaim to subside. In glowing terms he then introduced a wizened man, who stood up and walked briskly toward the piano at the front of the room. He seemed quite indifferent to the outburst of clapping which had greeted him when he rose. He adjusted the stool and sat down, eyeing the battered, dusty piano with open displeasure, and went into a medley of labour songs. Each tune was banged out with an unshaded mechanical clatter as though by a player-piano. “Tates, Mames, Kinderlach, Boyen Barricadn” gave way to “Ich Lieb Die Arbeit Ohn a Shier,” which yielded to “Du Arbeitsman Zei Grayt,” which slipped into “Hammerl, Hammerl Klap,” and so on and so forth. I found myself being relentlessly pulled back, by this conveyor belt of work songs, to the May Day parades that used to come bounding down Spadina in a glory of slogans and to the sound of a band, hired for the day, which alternated between “Arise Ye Prisoners of Starvation” and such martial stand-bys as the “Colonel Bogey March.”

The chairman waited for the acclaim to subside. In glowing terms he then introduced a wizened man, who stood up and walked briskly toward the piano at the front of the room. He seemed quite indifferent to the outburst of clapping which had greeted him when he rose. He adjusted the stool and sat down, eyeing the battered, dusty piano with open displeasure, and went into a medley of labour songs. Each tune was banged out with an unshaded mechanical clatter as though by a player-piano. “Tates, Mames, Kinderlach, Boyen Barricadn” gave way to “Ich Lieb Die Arbeit Ohn a Shier,” which yielded to “Du Arbeitsman Zei Grayt,” which slipped into “Hammerl, Hammerl Klap,” and so on and so forth. I found myself being relentlessly pulled back, by this conveyor belt of work songs, to the May Day parades that used to come bounding down Spadina in a glory of slogans and to the sound of a band, hired for the day, which alternated between “Arise Ye Prisoners of Starvation” and such martial stand-bys as the “Colonel Bogey March.”

In the old days, Spadina Avenue and its small tributaries, St. Andrews and Cecil Streets, where the workers who had left the factories en masse lined up for the parade formations, took on a yomtovdig, a festive, air. Those who marched with the union locals gathered on St. Andrews, adjoining the Labor Lyceum, and those who chose to parade rather as members of the Left or Right Poale Zion or the Workmen’s Circle would get together on Cecil Street, where a good many Jewish organizations in Toronto have their headquarters to this day. What with the fraternal orders, the youth groups, the schools, the sports sections, and other branches of these movements participating, police had to route traffic off neighbouring Ross and Beverley Streets to accommodate the crowds that had turned out to parade on the labor holiday.

For the residents of the Home for the Aged, which until recently was on Cecil Street, this day was always exciting. Bundled in their coats and scarves, they flocked to the curb and gaped with pleasure at the parade line forming across the road in front of the Jewish National Workers’ Alliance, or Farband Institute, now also located in another section of the city. “Ay, di yugnt, di yugnt” (Ah, the youth, the youth), they’d sigh as they watched the youthful members of the Hapoel soccer team, shivering and goose-pimpled in their jerseys and shorts, hoist amateurishly painted placards into the chilly spring air.

Once the old-timers were even treated to a minor riot when a sign reading “Down with Jabotinsky” was included in the parade. The Revisionists, whose club rooms were only a couple of blocks away from the Farband Institute, got wind of what the Labor Zionists were up to. Headed by their own soccer team they descended on Cecil Street and charged into the group as it was forming ranks in front of the Farband House. They got hold of the streamer and tore it to shreds. But the sign painter in the attic of the Farband Institute, working with the frenzy of the Sorcerer’s Apprentice, had another placard ready in a matter of minutes. Again the Revisionists charged, and again the banner was captured and ripped up. By the time the third sign was produced, the police had arrived. Order was restored, and with a somewhat tattered version of “Down with Jabotinsky,” the Labor Zionists marched off toward Spadina Avenue, where they merged with the main parade winding its way toward a park about a mile and a quarter away known as Christie Pits.

Once the old-timers were even treated to a minor riot when a sign reading “Down with Jabotinsky” was included in the parade. The Revisionists, whose club rooms were only a couple of blocks away from the Farband Institute, got wind of what the Labor Zionists were up to. Headed by their own soccer team they descended on Cecil Street and charged into the group as it was forming ranks in front of the Farband House. They got hold of the streamer and tore it to shreds. But the sign painter in the attic of the Farband Institute, working with the frenzy of the Sorcerer’s Apprentice, had another placard ready in a matter of minutes. Again the Revisionists charged, and again the banner was captured and ripped up. By the time the third sign was produced, the police had arrived. Order was restored, and with a somewhat tattered version of “Down with Jabotinsky,” the Labor Zionists marched off toward Spadina Avenue, where they merged with the main parade winding its way toward a park about a mile and a quarter away known as Christie Pits.

Since none of these organizations would have anything to do with the “United Front,” the Communists were forced to conduct their own marches every year. To avoid trouble the police always took elaborate care that the large right-wing parade, carrying their sizable quota of anti-Communist banners, never ran into the smaller left-wing group on its way to Queen’s Park.

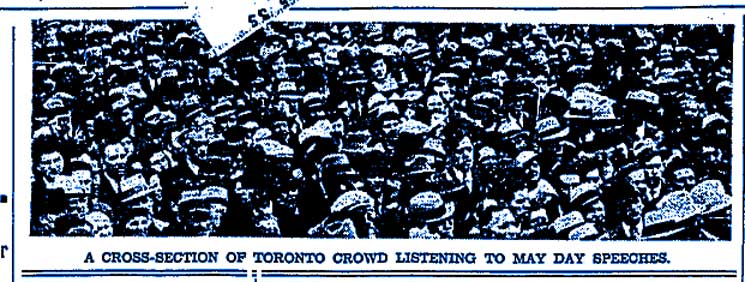

The front of the parade looked imposing, with the soccer teams of the Left and Right Poale Zion carrying their banners high and marching smartly in time with the drum and music. But the back ranks, far from the band, were made up of a weaving, awkward squad of chattering older men, their pockets bulging with the Forward, Tog, and the Morning Journal. The moment Christie Pits was reached all semblance of formation vanished and the crowd milled about a portable platform. Along with local speakers, there would invariably be an outstanding guest from New York such as Zerrubavel, Boruch Zukerman, the late Charney Vladeck, or the redoubtable Emma Goldman, who, by the way, eventually settled in Toronto and died here in 1940.

But the parade and the speeches were only a prelude to the main festivities, which took place during the evening in the auditorium of the Labour Lyceum. Here were the real speeches, here was the real enthusiasm, and here also were a few of the workers-turned-baalebatim who had gathered up enough courage to slip into the hall. These businessmen and shop-owners, who throughout the year were taken for granted as active members of one or another of the various labour movements, would by some implicit agreement be completely, crushingly, ignored at May Day rallies. They sat in the back rows of the auditorium, penitent and humble.

The gaudy banners which had been carried in the parade during the afternoon were trooped onto the stage by young men with the pomp and circumstance of centurions bearing Roman standards. A workers’ choir sang the same songs that I had just heard tumbling out of an old piano, under the fingers of the very same man. Only then there was the nimbleness of a mountain lion about him. With terrifying grimaces, and cunning agitations of his arms and shoulders, he got harmony out of a hundred men and women. Then came speech after speech calling for an end to the exploitation of man by man extolling the dignity of halutziut in Palestine, decrying the cynicism of the Communists, and pledging the might of labor in the struggle against the dark forces of fascism. Among the speakers there were always representatives of the Labour Zionist and the Workmen’s Circle Youth movements. In stilted shule Yiddish but with great feeling these eloquent youngsters pledged youth to fight for the working man’s place in the sun amid approving roars from the adults. “Unzer yugnt is unzer shtarkster koyach” (our youth is our greatest strength), the chairman would proclaim and the classn kampf seemed permanent, and its coming leaders invincible . . . .

That everyone in the small room had, like myself, been transported into the past was evident from the comments and wistful head-shaking which followed the applause after the old man finished playing. The chairman, under the enchantment of a nostalgic spell, ruminated among old glories recalled by the ancient choir leader; and the guest speaker, the last of the three participants, used the piano performance as a jumping off point for his address.

“What happened to the big choirs that used to sing these songs on May First?” the speaker threw out challengingly. He was a short, heavy-set man in his middle sixties with an aura of white fluff around his shining bald head.

What happened, he again demanded, to the teenage revolutionaries who once spoke with such dedication on May Day platforms? “Shreckt zich nit” (Don’t get alarmed), he assured the group with sarcastic emphasis: they were doing fine as professors, as scientists, as writers. There was only one thing wrong. “Merste fun zei hobn unz farratn” (Most of them have betrayed us). He pursued this theme for the rest of his address with the relish of a man finally able too unburden himself of a deep-felt complaint. The studies and creative writings of second-generation American Jews he conceded, occupy important places on the shelves of America’s cultural institutions. As a Yiddish journalist he had long studied the curious output of these talented young people.

“And do you know what I find there?” he exclaimed. “That we are the simple-minded papas and blintze-frying mamas who cannot begin to fathom the Weltschmerz of our fine-cut intellectual offspring. Our children have become anthropologists and sociologists and psychologists and all other kinds of ‘ologists.’ They study us endlessly to see if they can find out vos far min bashefen-ishn mir zeinen (what sort of creatures we are).

“Tell them about the lonely years we spent for our ideals in Siberia or in the prisons of Poland, tell them about our revolt against a reactionary world with no more than a few torn pamphlets, talk to them about our revolt against the might of the Czar and against our very own parents, and they will nod politely and tell you that they know all about it; we are ‘radicals of the East European shtetl.’ A specific type indexed along with other types such as the Hasidim and the Misnagdim. The revolutionaries of other peoples have been accorded places of honor in the histories of their nations. This is true of the United States, of France, of Britain, of all the others. But we will be remembered as peculiar Old Country types.

“If not socialism what, you will ask, is the answer our cultured children have worked out for themselves? … Religion!” he blurted out, revealing what to him must have been the ultimate ignominy. “Not the religion of the Ten Commandments our fathers preached, but of the ten polite suggestions of the psychologists. Religion, according to the modern generation, is good for the nerves. So here we are back in the Bes Hamedrish, only the sh’liach tzibur now is Professor Freud. At least the religion of our fathers was something militant. Opiate though it was, it gave them something to live for. But what is this new God you read so many polemics about … peace of mind … a nerve tonic!” he thundered.

“The worst of it,” he continued, “is that the institutions we spent our very lives building up on this continent have not escaped this God of theirs. They have brought back Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur t’fillos (prayers) into our own buildings; they have introduced the Bar Mitzvah and other religious practices into schools we created and fought to keep secular. Yes, we have been betrayed “

With this, the speaker’s castigations came to an end, and he left one final thought with his audience before he sat down. “At our time of life,” he said, more calmly, “we should be handing over the reins to a younger group of leaders, but we have been ignored by our youth as we were despised by our parents. If our generation is not to be suspended in mid-air, if it is to survive this rejection and leave the imprint of its ideas on the course of human events, there is no alternative than for us who have become old in the struggle to uphold our socialist ideals with the vigor of youth.”

With this, the speaker’s castigations came to an end, and he left one final thought with his audience before he sat down. “At our time of life,” he said, more calmly, “we should be handing over the reins to a younger group of leaders, but we have been ignored by our youth as we were despised by our parents. If our generation is not to be suspended in mid-air, if it is to survive this rejection and leave the imprint of its ideas on the course of human events, there is no alternative than for us who have become old in the struggle to uphold our socialist ideals with the vigor of youth.”

The speaker’s sustained outcry against the younger generation ignited the entire group with righteous indignation. When the old choir conductor struck up the first chords of the “Internationale,” the fifty men and women sang out “Shtay’t oif ihr alle verde shklafn” with defiance. They were not going to take the desertion lying down.

During the closing moments of the hymn, the caretaker came up and stationed himself beside the light switches with that janitorial determination that will not be denied. The gentle chairman wilted under the caretaker’s passive gaze, and he closed the meeting in a halting, abstracted way as though some final announcement preyed on his mind but he couldn’t quite recall what it was. He fumbled away the defiant mood created by the speaker. As soon as the people left their seats, the janitor started dousing lights.

Outside, a cold, driving spring rain needled into the marrow of the old people huddling under the small marquee as they came out of the Labor Lyceum. Every few moments three of four individuals would brave the elements and charge for another automobile, angle-parked against the curb. As each car pulled away, it left a dry patch of asphalt that was quickly blackened by the rain. Spadina Avenue was deserted. Store awnings flapped in the wind and neon signs blinked lurid and futile out on the abandoned street, their reflections quivering in wind-swept puddles on the sidewalk. As one looked northward, one could follow the journey of the cars from the Labor Lyceum to the Famous Dairy Restaurant, two blocks away. Through the rain, figures could be faintly discerned bolting cars and running into the restaurant for coffee and Danish. ♦

View of Spadina Avenue, looking north from outside Labour Lyceum, with former Hebrew Men of England Synagogue on right and “Grossman’s Tavern” beside it (cta)