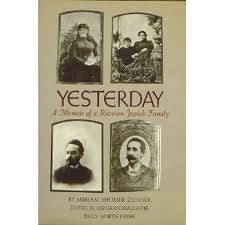

Yesterday, A Memoir of a Russian Jewish Family by Miriam Shomer Zuner is a lovely reminiscence by Miriam Shomer Zunser, the American daughter of Yiddish novelist Nochim-Mayer Shaikevitsch. It was originally published in 1939 and a second edition, edited by Zunser’s granddaughter Emily Wortis Leider, was printed by Harper & Row in 1978.

Yesterday, A Memoir of a Russian Jewish Family by Miriam Shomer Zuner is a lovely reminiscence by Miriam Shomer Zunser, the American daughter of Yiddish novelist Nochim-Mayer Shaikevitsch. It was originally published in 1939 and a second edition, edited by Zunser’s granddaughter Emily Wortis Leider, was printed by Harper & Row in 1978.

Zunser’s unself-conscious narrative focuses on various members of her family in 19th-century Belarussia, principally in Pinsk. Some are impoverished, others quite well-to-do. Through a succession of folksy and often remarkable anecdotes, it paints a rich picture of Pale of Settlement life.

Like Gluckl of Hamelyn and other female Jewish family chroniclers, Zunser penned her narrative for own children, likely with no thought of publication. She had an amazing knowledge of family events that occurred decades before she was born. I liked her book from the moment I read its opening sentence: “Your great-grandfather had twenty-four children, all by the same wife.”

Zunser tells many tales of her illustrious great-grandfather, Reb Michel Bercinsky. He once rescued the Pinsk shul from an onerous tax burden by taking the government to court; he also gained the respect even of thieves in the town who abided by a gentleman’s agreement among them never to break into his house.

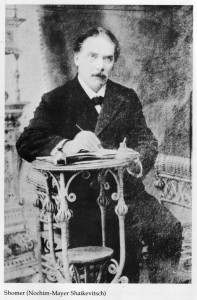

She also recounts many memorable episodes concerning her father, the prolific Shaikevitsch (“Shomer”), whose Yiddish romances eventually fell from popular and critical favour. Space allows me to convey only one of Zunser’s anecdotes — about her paternal grandfather, Reb Gavriel Goldberg of Nesvizh — at the length it deserves.

A wealthy businessman who exported goods and raw materials around the Baltic, Reb Gavriel had reached the allotted biblical lifespan of 70 with still no offspring. He yearned for a “kaddish,” a son to utter prayers for him after his death. His plan to divorce his wife and seek a young bride stirred the rabbis of Nesvizh to debate. Although Jewish law permitted a man to divorce a barren wife after ten years, they forbade the divorce because he had waited much longer. “Reb Gavriel had waited almost fifty years,” Zunser recounted, “and it was too late.”

A rabbi was found in another town who would grant the divorce; and even though his wife refused to receive the get (divorce decree) into her hands, Reb Gavriel went ahead with a second marriage a few months later. The rabbi, Reb Nochim-Mayer, also officiated at the ceremony; and startled everyone by raising his hands to heaven and proclaiming:

“‘If this union has come about against the will and law of God, may it prove barren as the sands of the desert! If, however, I have acted according to the teachings of our lawgivers and the will of the Almighty, may it be blessed with many children and may even you, Reb Gavriel, together with your wife, live to marry off the youngest of your offspring!’

“Then he turned to the wide-eyed wedding guests. ‘Say Amen!’ he commanded. ‘Amen!’ they whispered in secret foreboding.”

Watched by every Jewish eye in Nesvizh, Reb Gavriel’s petrified young bride soon became pregnant; hearing the news, his first wife accepted the “get” and the money he provided, and went off to Palestine to die. “She could not give one child to her people; she would give her bones to mix with the dust of their land.”

Reb Gavriel’s second wife ultimately produced nearly a dozen sons and daughters, and he indeed lived to see the youngest of his offspring married according to the rabbi’s proclamation. He died soon after at the age of 110, Zunser related, with plenty of kaddishes to say the prayers for his departed soul. ♦

© 2005