A new critical biography of Mordecai Richler by Reinhold Kramer, a Manitoba English professor, offers an engaging, thorough and microscopic examination of the life and letters of the iconic Canadian Jewish novelist and essayist, complete with some penetrating psychological insights.

A new critical biography of Mordecai Richler by Reinhold Kramer, a Manitoba English professor, offers an engaging, thorough and microscopic examination of the life and letters of the iconic Canadian Jewish novelist and essayist, complete with some penetrating psychological insights.

In researching Mordecai Richler: Leaving St. Urbain (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2008), Kramer attained access to never-before published material from the Richler archive; he spent months studying the contents of some 265 boxes of papers, letters and other documents on deposit at the University of Calgary. He also attained the cooperation, if not outright blessing, of various Richler family members.

One of Kramer’s well-demonstrated theses is that Richler rarely strayed far from his own life experiences in his fiction. As this astute literary biographer puts it, “[N]o matter what sophisticated literary structures Richler built on top of his foundations, the foundations were almost always roman-a-clef.”

Richler’s family and circle of cognoscenti knew this only too well. His mother, Lily, was shocked upon reading Joshua Then and Now that Mordecai had made the protagonist’s mother a strip-teaser, and nothing could persuade her that he hadn’t been writing about her. “Can you imagine, he said I was a strip-teaser!” she would tell people. When Richler’s first quality novel, Son of A Smaller Hero, appeared in 1955, his literary associate Brian Moore scolded him that there were “too many real people” in it.

Richler’s family and circle of cognoscenti knew this only too well. His mother, Lily, was shocked upon reading Joshua Then and Now that Mordecai had made the protagonist’s mother a strip-teaser, and nothing could persuade her that he hadn’t been writing about her. “Can you imagine, he said I was a strip-teaser!” she would tell people. When Richler’s first quality novel, Son of A Smaller Hero, appeared in 1955, his literary associate Brian Moore scolded him that there were “too many real people” in it.

Indeed, Kramer presents a handy chart indicating that the novel’s protagonist Noah Adler is really Richler, Adler’s father is really Richler’s father, Adler’s mother is really Richler’s mother, and so on. Richler’s famous grandfather, Rabbi Yudel Rosenberg, an author and Hebrew scholar in his own right, is also represented.

To punish her five-year-old boy, Richler’s mother once called Eatons department store and, with Mordecai listening, told them that she wanted “to exchange my bad little boy for a nice girl.” As an adult, Richler acted on a reciprocal impulse and all but cut his mother out of his life. Kramer marshals all the considerable evidence at his disposal to examine the author’s thorny and uncomfortable relationship with his mother and how it presented itself in his fiction.

As an interesting revelation, Kramer uncovers the manuscript of an early novel called The Rotten People, an “unpublishable” book about unlikeable people doing ugly things; he calls it “a very bad novel.” Richler, a brash and talented youngster in his early twenties, was writing about his family and the people, mostly Jewish, that he knew. Because of the unresolved anger towards his mother that he carried throughout his life, maternal figures in Richler’s fiction often come to bad ends. As Kramer observes, Son of a Smaller Hero marked the second time that Richler killed off his mother in fiction.

That novel also marked Richler’s first success as a writer. A virtual unknown, he turned up at a literary agent’s office in Paris in 1954, “strange, wild-eyed, diffident with a great big manuscript under his arm.” The agent “read the book that very night and claims to have jumped out of her chair at the recognition of both his talent and the impossibility of getting the mammoth published,” Kramer writes. “The next morning she phoned and said, ‘Young man you should not know such words at your age.’” But she took the book and helped him “rein in the excesses of his style” and find a publisher.

Kramer observes that Richler’s early writing ranges “from a somewhat romanticized Sholom Aleichem voice, to a clipped version of Callaghan and Hemingway, to a very showy attempt at avant-garde colloquialism.” Eventually he meshed “formal literary qualities with a colloquiality rooted in Yiddish inflections and English everyday speech.” Although Richler tended towards bohemianism in his footloose Paris days, he discovered that, if he wanted to survive as a writer, he could not cut himself free from the St. Urbain Street domain of his past.

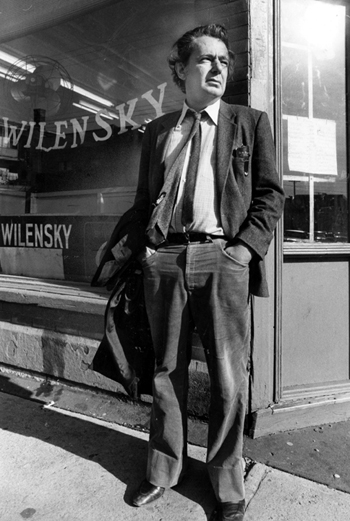

In 1947 the teenaged Richler belonged to a Zionist organization and marched in a rally down Saint Catherine Street, waving Israel flags, singing Am Yisrael Chai, and dancing the hora. Several years later, needing a complete break with his past, he began his long self-imposed exile in Paris, Ibiza and London. Still, he became famous satirizing and ridiculing the Jewish world he had known in acclaimed novels such as The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz (1959), St. Urbain’s Horseman (1971) and Solomon Gursky Was Here (1989). The irony of his life was that all roads led him back to the Jewish Montreal he had tried so hard to escape, which would always comprise the essence of his internal landscape.

The author of much ephemeral magazine satire, Richler sometimes found himself in a Catch-22 situation because editors who admired his work because “it didn’t reproduce middle-class Anglo-Saxon” values sometimes told him they’d had their fill of satire on the Jews. Richler moved back home to Montreal in the 1970s and redefined himself in the 1980s as a highly visible opponent of the Parti Quebecois, ridiculing the undemocratic and risible wiles of the separatist movement in international forums such as the New Yorker magazine. In a chapter titled “Tongue Trooper,” Kramer observes that Richler turned polemical and fiery around 1988.

“In the late 1980s and throughout the 1990s, no fiction writer was more significant in the Canadian polity than Richler,” he writes. “While his stance alienated many Quebecois, his federalist political involvement made him a truly national figure, in a way that no mere novel could do. Montreal’s Jews began to invite him to Jewish book fairs, and even to father-and-son breakfasts. Once the prodigal son of Montreal Jews, he now starred on the ‘lox-and-bagel circuit.’”

Several good books have appeared on Richler in recent years, including Joel Yanofsky’s fanciful Mordecai & Me: An Appreciation of a Kind, and Michael Posner’s engrossing oral history, The Last Angry Man: Mordecai Richler. With Mordecai Richler: Leaving St Urbain, Reinhold Kramer brings Richler scholarship to a much higher level. The book is diligently researched, well balanced, critically nuanced and well written. While it offers much more information than casual readers will require, scholars and diehard Richler fans will find it highly informative and entertaining. ♦

© 2008