His name was Moses; he was a leader of his people; he spent much time in Egypt and the desert; he wandered incessantly; he is associated with a fiery mountain and the holiday of Passover; and his life lasted longer than a century.

These traits describe the biblical Moses, of course, but they also refer to a more contemporary historical figure whose accomplishments were such that it would not be inappropriate to remember him in this season of Passover.

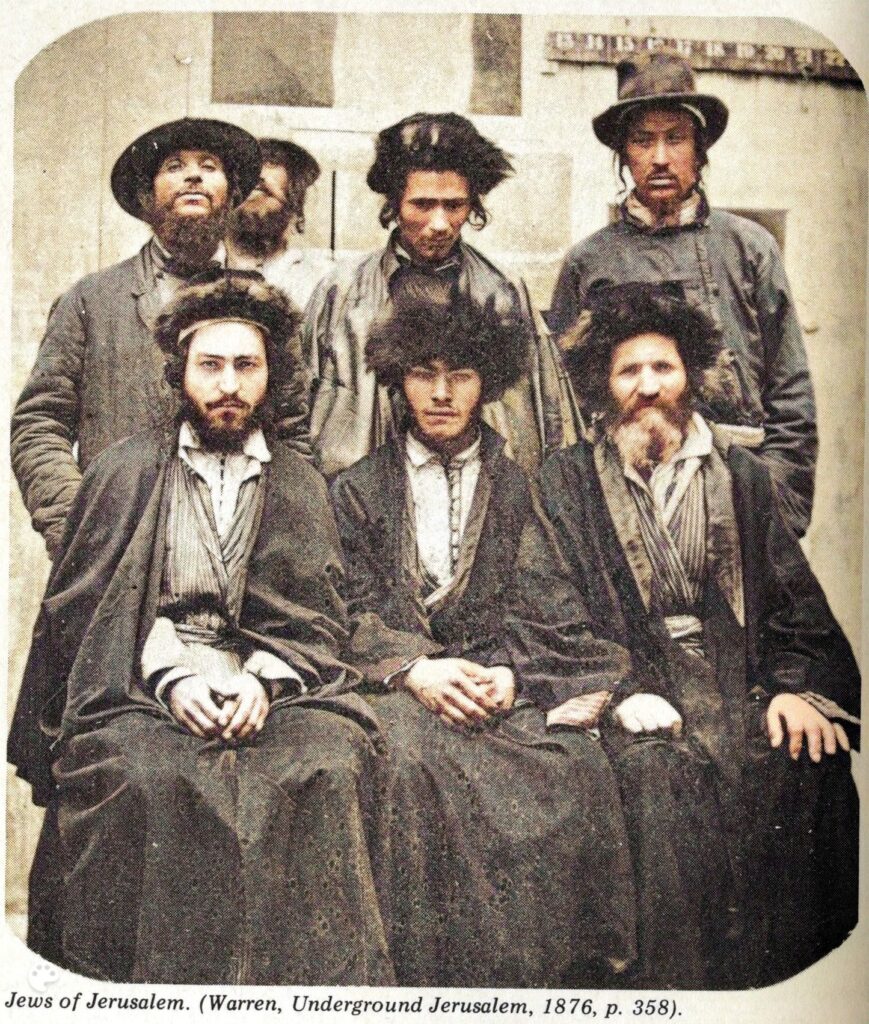

The wealthy English businessman-philanthropist Sir Moses Montefiore (1784-1885) ventured seven times from his home to the Jewish Holy Land, showing a continuous interest and generosity towards the sprinkling of Jews who then lived in the four Jewish holy cities (Jerusalem, Tiberias, Safed, Hebron) of Ottoman-ruled Palestine.

In the days when global travel required considerable wealth, time and fortitude, he also journeyed on humanitarian missions on behalf of his co-religionists to such farflung places as Morocco (1864) and Romania (1867). In Russia, which he visited in 1846 and 1872, he pleaded with the Czars, like his biblical namesake before Pharoah, to relieve the oppression of his people; he returned from the second trip assured that a bright new age was dawning for Russian Jewry.

Montefiore — whose name evokes etymological images of a Sinai-like “mountain of fire” — first saw Jerusalem in 1827. The experience so deeply affected him that he became a strictly observant Jew and dedicated himself to bettering the conditions of life of his Jewish brethren, wherever they might be.

Today, air-travellers leaving London can easily be in Jerusalem in less than ten hours, but in 1827 it took that length of time for the Montefiores and their party to make Dover, where they joined a ship crossing to the European mainland. They left England May 1 on their initial journey to Palestine and reached Jerusalem October 17, but were compelled to stop in Egypt for some time enroute. “Several times they felt some doubt whether it would be possible for them to reach their destination,” wrote Albert M. Hyamson in a monograph on Montefiore’s life and times.

“While on the sea they were beset by rumours of pirates, and on land, with those of war, and in fact, left Cairo hurriedly in consequence of sudden unjustified warnings of imminent trouble between Egypt and Turkey.” Upon reaching Palestine, Lady Montefiore recorded in her diary with some satisfaction that she was one of only six Western European women known to have visited the country in the course of the century.

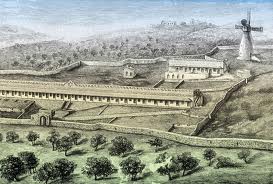

The greatest Jewish benefactor of his day, Montefiore left his mark on the Jewish Holy Land. He planted the first seeds of Israel’s lucrative citrus crop near Jaffa and founded the first Jewish quarter outside the old walls of Jerusalem. A daring landmark, Montefiore’s windmill is a focal point of the Jerusalem neighborhood of Yemin Moshe, named in his honor and memory. A small museum here displays one of the simple carriages which conveyed the Montefiores across Europe and the Levant.

Sir Moses, who presided over Britain’s Board of Deputies of the Jews for some 40 years, has been called the “last of the shtadlanim” or official protectors of the Jews of other lands. It was in this capacity that he betook himself on an urgent mission to Cairo and Constantinople at the height of the infamous Damascus Affair of 1840.

Convinced that local Jews had slaughtered two Christians to use their blood in Passover matzah, officials in the Syrian capital had tortured dozens of Jews, extracted confessions, and put four of them to death. As the populace at large had eagerly accepted the veracity of the ancient blood libel, anti-semitic sentiment had reached a fever pitch and the beleaguered Jewish community faced a constant danger from mobs.

In a meeting with the Sultan of Turkey, Montefiore secured from the ruler a promise of protection to the Jews as well as the issuance of an official firman proclaiming the charges of ritual murder as false. Upon his return to England, he was honored by Queen Victoria for his “unceasing exertions on behalf of his injured and persecuted brethren in the East, and of the Jewish Nation at large.”

Perhaps more than other similar events, the Damascus Affair shocked the scattered Jews of the Diaspora into the recognition that they were still a unified nation, capable of acting across international lines in matters of Jewish welfare. Montefiore remained active in international Jewish affairs until almost his hundredth birthday, which was celebrated as a public holiday by Jewish communities around the world. He died on July 28, 1885 — “and the children of Israel wept for Moses.” ♦

© 1999