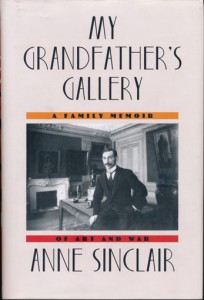

REVIEW: My Grandfather’s Gallery: A Family Memoir of Art and War, by Anne Sinclair (Farrar Strauss & Giroux)

Born in New York in 1948, the prominent French-Jewish journalist Anne Sinclair says that while the heroic stories of her paternal grandparents, who had stayed in France during wartime, had always resonated deeply within her, she was never drawn to the same degree to the experiences of her maternal grandparents, who had fled to New York in the same perilous period.

Born in New York in 1948, the prominent French-Jewish journalist Anne Sinclair says that while the heroic stories of her paternal grandparents, who had stayed in France during wartime, had always resonated deeply within her, she was never drawn to the same degree to the experiences of her maternal grandparents, who had fled to New York in the same perilous period.

But all that changed after her mother died in 2006, and Sinclair delved into several boxes of her mother’s letters, documents and photographs that had lain untouched for decades. The contents included an unfinished autobiography of her maternal grandfather, Paul Rosenberg, who had owned an influential art gallery in Paris and had been one of the most important art dealers in Europe until the Nazis rolled into Paris in June 1940.

In My Grandfather’s Gallery: A Family Memoir of Art and War, Sinclair pays homage to this pivotal figure in the art world of the early 20th century, who was on intimate terms with some of the leading artists of the early modernist period. She also traces the Nazi’s atavistic campaign against “degenerate art” and their brutish pillage of Europe, especially their looting on a massive scale of artworks belonging to Jews.

The notion that art could be “degenerate” had been circulating in European culture at least since 1893, when Jewish social critic Max Nordau used the word “Entartung” or “degeneracy” in reference to art. In his famous critical work Degeneration, Nordau observed that modern art at the end of the 19th century was a mirror in which one could see clear signs of the breakdown of traditional social values as well as the various neuroses and hysterias of European society. That trend in modernism, of course, became glaringly obvious after the First World War.

As early as 1909, Kaiser Wilhelm may have one of the first to harness Nordau’s ideas to a censorious objective when he fired the director of a major gallery for buying impressionist paintings. The concept of “degenerate art” gained renewed currency in the 1920s when a group of philosophers invoked the phrase in protest against modernism. After 1933, the Nazis took the next logical step by banning “degenerate” works and expropriating them wherever possible. Terrified artists were forbidden not only to show or sell their works, but even to buy brushes, canvases or paint; many went into exile.

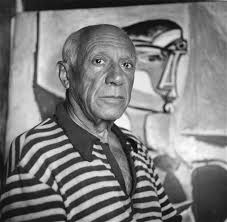

Widely considered the epicenter of the Paris avant-garde, the Galerie Rosenberg at 21 rue La Boetie was famous for its displays of paintings by Picasso, Braque, Derain, Matisse, Leger, Laurencin, Toulouse-Lautrec, Ingres, Cezanne, Seurat, Rousseau, Monet and Renoir.

Both born in the same year (1881), Rosenberg and Picasso were extremely close and saw each other as “spiritual brothers.” Picasso sketched portraits of members of the art dealer’s family; Rosenberg picked canvases straight from the artist’s studio and personally hung them in his gallery for each of the many solo Picasso exhibitions he organized over the years. “If Picasso’s painting took off in the 1920s, it did so not least because Paul knew how to promote the painter and guide him in directions other than cubism,” Sinclair writes of her grandfather.

Both born in the same year (1881), Rosenberg and Picasso were extremely close and saw each other as “spiritual brothers.” Picasso sketched portraits of members of the art dealer’s family; Rosenberg picked canvases straight from the artist’s studio and personally hung them in his gallery for each of the many solo Picasso exhibitions he organized over the years. “If Picasso’s painting took off in the 1920s, it did so not least because Paul knew how to promote the painter and guide him in directions other than cubism,” Sinclair writes of her grandfather.

In 1939, just weeks before the outbreak of war, the Germans held an auction in Lucerne of 126 paintings and sculptures that had been confiscated from museums and private collections in Germany. “Many collectors, unable to resist the temptation to buy outstanding works of art at low prices, attended,” Sinclair writes. “Paul warned potential buyers that any currency the Reich harvested from this sale ‘would fall back on our heads in the form of bombs.’ ”

It was another, unrelated Rosenberg – the Nazi propagandist Alfred Rosenberg – who led the National Socialist campaign against degeneracy, which included any form of physical distortion of the human being in art. Alfred Rosenberg took over Paul Rosenberg’s well-appointed gallery and used it as headquarters for the antisemitic Institut d’Etude des Questions Juives, the Institute for the Study of Jewish Questions. Alfred Rosenberg also set up the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg, the chief organization in the looting operation against Parisian art dealers and Jewish owners. The booty was taken to the Louvre and another museum where it was photographed, evaluated, and wrapped for shipment to Germany.

By then, Paul Rosenberg had already put some of his artworks into storage under the name of his non-Jewish chauffeur, and had sent other pieces abroad. He also helped to prepare the first big Picasso retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and a Picasso exhibition at the Art Institute in Chicago in 1939 and 1940. “Paul loaned more than 30 canvases” to these exhibitions, Sinclair writes, “which meant these paintings had escaped the clutches of the Nazis.”

More importantly, Rosenberg and his family also escaped the Nazi’s clutches, having fled to Portugal as refugees. Here’s how he described the experience in his diary: “Imagine a man who has everything in life . . . and who, a week later, has lost his business, his fortune, his friends. I was sitting on a stone wall with a boiled egg and a crust of bread and I couldn’t help laughing.” Eventually the family made it to London and then New York.

With the topic of looted artworks and restitution central to the current film Woman in Gold and numerous other recent books and movies, My Grandfather’s Gallery appears at a time of heightened interest in the subject. (The book was originally published in French in 2012, and came out in English translation in 2014.)

With the topic of looted artworks and restitution central to the current film Woman in Gold and numerous other recent books and movies, My Grandfather’s Gallery appears at a time of heightened interest in the subject. (The book was originally published in French in 2012, and came out in English translation in 2014.)

The story, which combines a Jewish family’s dramatic wartime saga with an insider’s view of the art world, bears parallels with Edmund de Waal’s 2010 family memoir, The Hare With the Amber Eyes.

Sinclair’s book also bears comparison with a biography of Edna Ferber that I once read in which the author decided to tell her subject’s life in backwards order; it was an experiment that did not work. Sinclair doesn’t exactly follow that plan but, in my opinion, she undercuts the power of her narrative significantly by not telling the story in chronological order. For this reason, I turned a lot of pages before warming to the story — the heart of which is the relationship between Rosenberg and Picasso. ♦