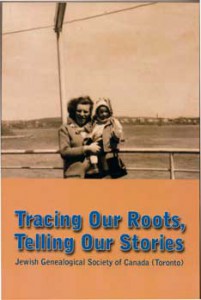

To mark its 25th anniversary, the Jewish Genealogical Society of Canada (Toronto) has published a book of 44 genealogy-related stories written by its members.

To mark its 25th anniversary, the Jewish Genealogical Society of Canada (Toronto) has published a book of 44 genealogy-related stories written by its members.

The stories in Tracing Our Roots, Telling Our Stories are diverse and range freely over geography and time, encompassing both the Old World and the New from a couple of centuries ago to the present. The settings include Galicia, Romania, Russia, Ukraine, Poland, Czechoslovakia and Israel; one ranges as far off the beaten path as Barbados, another the island of Mauritius. Canadian locales include Melfort, Saskatchewan, St. John’s Newfoundland, the northern town of Waubaushene, Ontario, and downtown Toronto.

In this miracle age of internet genealogy, many of us have found passenger manifests of one or more of our ancestors, but relatively few of us ever hear the full story of the struggle and challenge behind a typical sea crossing. In “Yetta’s Gift,” author Sharon Singer relates the moving tale of her grandmother’s crossing with four children after her husband, who was already in Toronto, sent five ship’s tickets back to her in Galicia.

“When Yetta tried to board the ship with her four children, the ticket-taker told her that the tickets were not sufficent,” she writes. “He insisted that a further payment was required. Unable to speak English, Yetta was forced to give up her gold wedding ring and earrings. She never wore a wedding ring again.”

Several days into the voyage, Yetta’s small provision of food had been exhausted and her children began to grow weak from hunger. Traveling in steerage, she stood at the bottom of a staircase that connected to an upper deck and pleaded with a well-dressed woman for food. “The woman’s heart was touched by Yetta’s plight and each day she brought food to the stairwell where Yetta would be waiting. Without knowing her name, Yetta thanked her and blessed her each Friday night for the rest of her life.”

No mere genealogical document could convey such heart-breaking vignettes. Rather, they are the stuff of oral history and first-person narratives of the sort that fill this 248-page book.

In “Return to Ostrowiec,” Anne Stein tells of her family’s existence in the Polish town where she was born, the family’s immigration to Toronto in 1936 and subsequent experiences, and her eventual return to her home town three years ago. (Stein told her tale to Evelyn Steinberg and Rodeen Stein, who preserved it as a written narrative.)

“The First Jewish Kvutza in Russia,” a story by the late Moishe Faerman translated from Yiddish by his daughter Sarah Faerman, is about an attempt by a group of Zionists to establish a Jewish communal farm, with Saturday as their day of rest. “Unfortunately our neighbours under no circumstances would allow us to work in the fields on Sundays. They also refused to believe that we were working according to Communist principles. They couldn’t believe that a Communist would work on his own with no one over him. In their view, a Communist was one that plundered and confiscated.”

As one might expect, numerous stories deal with the Holocaust and the myriad displacements it generated. In “After Vienna,” Henry Wellisch recounts his dramatic story as a wartime refugee from Vienna being denied entry into Palestine and being shipped by the British to a refugee camp in Mauritius. He eventually reached Israel, served in the army, and brought his parents to Canada in 1952. Another Holocaust piece, “A Final Goodbye to My Lost World,” was contributed by well-known author Simcha Simcovitch.

For David Price and Howard Zakai, the impulse to reconstruct the history of their shared Gorlicki family tree in Chmielnik, Poland was sparked by the realization that the history had been all but obliterated by the Holocaust, emigration and the passage of time. They and other researchers reconstructed a family tree that now boasts more than 1,500 descendants.

Some stories, such as “My Uncle Ellah” by Ellen Shumak Monheit, describe pivotal personal moments. In this tale, the author explains that she first felt the impulse to research and record her family history upon the tragic death of an uncle when she was seventeen. “That night, 10 February 1959, I decided to become the historian and archivist for my family. I was afraid that if I did not write down important events, I would be partially responsible for my family’s eventual disappearance. Therefore I essentially assumed the responsibility for ensuring that this would not happen.”

Other equally riveting accounts include “In Search of Mishpocha,” by Peter Jassem; “The Mysterious Tombstone,” by Ruth Chernia; “Palestine 1935,” by Judith Ghert; “Oh, The Family Stories They Love to Tell” by Rachel Aber Schlesinger; “A Prairie Vignette,” by Pearl Kasdan; “My Grandmother Gittel,” by Lorraine Cogan Kerzner; and “Discovering Family History Through the Translated Yiddish Word,” by Miriam Beckerman.

In fact, each author seems to make a unique contribution. Hard to believe that the Jewish Genealogical Society began soliciting manuscripts for this project only one year ago.

Despite the wide variety of subjects and settings, one may discern a common thread in these stories. Jews today seem to have an imperative need to collect and preserve the shards of our family histories and reassemble them as one might the fragments of a fine china plate that has been shattered on the floor. Jewish genealogy may thus be seen as a form of tikkun olam, repairing the world.

Tracing Our Roots, Telling Our Stories is available by mail for $25 plus $5 shipping and handling ($10 in US) from the Jewish Genealogical Society of Canada (Toronto), P.O. Box 91006, 2901 Bayview Ave., Toronto, ON Canada M2K 2Y6. www.jgstoronto.ca ♦

© 2011