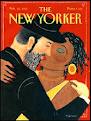

Since I first started writing professionally nearly 35 years ago, I’ve always held the dream of getting published in the New Yorker. So far, it hasn’t happened. As the saying goes, a man’s reach should exceed his grasp, else what’s a heaven for?

Since I first started writing professionally nearly 35 years ago, I’ve always held the dream of getting published in the New Yorker. So far, it hasn’t happened. As the saying goes, a man’s reach should exceed his grasp, else what’s a heaven for?

In the meantime, I’ve read many interesting books about the celebrated Manhattan-based weekly magazine that regularly fills its pages with brilliant articles by some of the world’s best writers. This column focuses on several books about the New Yorker as well as a special computer-age treat geared for true New Yorker mavens.

The legendary and revered William Shawn (1907-1992), who was at the magazine’s helm during its golden period from 1952 to 1987, was an ideal magazine editor. As Ved Mehta writes in his lovely if overly hagiographic memoir Remembering Mr. Shawn’s New Yorker: The Invisible Art of Editing (Overlook Press), Shawn sheltered and mollycoddled his writers to an extraordinary degree, putting them on salaries and giving them offices, often in exchange for “the pressureless pressures of being left alone to do whatever they liked, and meet no demands of any kind.”

Some writers had nervous breakdowns or developed writer’s block under the strain of such intense artistic freedom, but many others produced sparkling gems, helping the magazine earn its consistent reputation as the top newsstand choice for a wonderfully good read, issue after issue. In fact, Shawn accepted many more articles than he could publish. When he retired in 1987, he left some 5,000 unpublished pieces in the story-bank; most were killed by his successor.

So protective was Shawn of his staff writers that he turned a blind eye when Maeve Brennan, who wrote occasional pieces, moved into the office, cooking in her cubicle and sleeping in the ladies’ room. Informed that Brennan’s behaviour was becoming increasingly erratic, even violent, Shawn “would say, ‘She’s a beautiful writer,’ and quickly walk away. He seemed to be at a loss to know how to handle her.”

He was no less protective of the New Yorker itself. As Mehta explains, he knew the magazine’s content and style were geared primarily for urbane intellectuals and not the common masses; consequently, he never sought a mass circulation. As an operational strategy, he preferred to keep the circulation low, even to go out of business, rather than dilute the editorial content, surrender to a gimmick or fad, or accept unseemly advertising that would lower the magazine’s character.

Longtime New Yorker contributor Lillian Ross reveals a more private side of Shawn in Here But Not Here: My Life with William Shawn and The New Yorker (Random House). The unmarried Ross recounts her lengthy relationship with the married family man, whose second home was her own Manhattan apartment. Shawn kept himself invisible to his writers, Ross explains: he existed to fulfill their needs, not the other way around. Surprisingly, he saw himself as a frustrated writer who sublimated his own wish to write in order to help others achieve theirs.

“He would often say that he felt he did not ‘exist,’” Ross writes. “He felt eternally designated to serve others in their endeavors; at the same time he struggled to hold on to, as he put it, ‘a fading belief in my own reality.’ He was, in short, oddly cursed by his great gift for making it possible for others to communicate their art, for he was never able to give that gift to himself.”

Shawn’s dynamism was such that no two writers portray him in the same way, and Renata Adler, in her book Gone: the Last Days of the New Yorker (Simon & Schuster), disputes aspects of both Mehta’s and Ross’s portrayals. Hers is perhaps the best-rounded book, even if her thesis — that the New Yorker has deteriorated so much since Shawn’s day that it is essentially dead — is a rumour that has been greatly exaggerated. The magazine still has a pulse, after all, as well as a circulation several times higher than in the days before it became a commercialized Conde Nast publication.

Ben Yagoda’s highly enjoyable About Town: the New Yorker and the World It Made (Da Capo Press) delivers a rich vein of lore and anecdotes about many literary greats: Vladimir Nabokov, J. D. Salinger, John Cheever, A. J. Liebling, Harold Ross, Katharine Angell, Calvin Trillin, Pauline Kael, et. al — the list seems endless.

Such books may leave readers craving a taste of the real thing. In the post-Shawn days, as Mehta laments, the magazine’s new corporate owners cravenly began to sell thematic packages of cartoons and books. Those that have earned a hallowed place on my book shelf include The New Yorker Book of War Pieces (Schocken Books); The Fun of It: Stories from the Talk of the Town, edited by Lillian Ross (Modern Library); and Life Stories: Profiles from the New Yorker, edited by David Remnick (Modern Library).

Remnick, the magazine’s current editor, also recently put out Reporting, a collection of his own New Yorker profiles (Random House). Subjects include Philip Roth, Vladimir Putin, Natan Sharansky, Sari Nusseibeh and the PLO, Amos Oz and Benjamin Netanyahu.

For those unsatisfied with bottled samples and feel the need to return to the very waters of Lourdes, so to speak, here is the piece de resistance: The Complete New Yorker (Random House), a series of eight disks containing every page of every issue from 1925 to 2006. Shopping around, I discovered this most desirable package selling for $120 in local stores, $89 on Chapters-Indigo online, and an irresistible $39.95 ($60 with tax and shipping) via the New Yorker Store’s website. The delivery took only 10 days.

It’s an awesome feeling, having such a wealth of great reading at one’s fingertips — far too much to begin enumerating here. (Okay, just one example: at least two uncollected stories about the Glass family by J. D. Salinger.) All I need now is about a year of free time to catch up with my reading. Happy Chanukah, everyone. ♦

© 2007 by Bill Gladstone