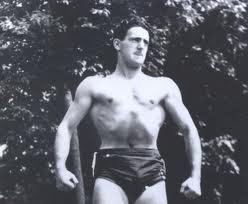

Ben Weider, who with his brother Joe founded a billion-dollar bodybuilding empire and helped launch Arnold Schwarzenegger’s career in the United States, died October 17 (2008) of heart failure in his native city of Montreal at the age of 85.

Ben Weider, who with his brother Joe founded a billion-dollar bodybuilding empire and helped launch Arnold Schwarzenegger’s career in the United States, died October 17 (2008) of heart failure in his native city of Montreal at the age of 85.

Weider was also a collector of rare Napoleonic artifacts, and donated some sixty valuable pieces to the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. The objects form the heart of a new permanent gallery on Napoleon that opened six days after Weider passed away.

“It was a sharp disappointment to everyone who knew and loved this guy that he died just a few days before the gallery opened,” said his friend, Montreal writer Joe King. “It was a crushing thing for those who were close to him.”

It was Ben’s brother Joe, a scrawny teenager, who first began lifting barbells to make himself more capable of responding to antisemitic taunts. Ben Weider built his own barbells from old car wheels and axles, then began his publishing empire for $7, mimeographing his first publication on a Gestetner machine. The brothers’ corporate empire eventually came to include magazines such as Muscle & Fitness, nutritional supplements, and a line of home and gym exercise equipment.

After serving in the war, they founded the International Brotherhood of Body Builders in 1946 and brought Arnold Schwarzenegger, then a little-known Austrian bodybuilder, from his home country to America, where he became a movie star, then governor of California.

After serving in the war, they founded the International Brotherhood of Body Builders in 1946 and brought Arnold Schwarzenegger, then a little-known Austrian bodybuilder, from his home country to America, where he became a movie star, then governor of California.

“I wouldn’t have known how to come over here [on my own],” Schwarzenegger told the Associated Press upon learning of Weider’s death. “I mean, I sure didn’t have the money. So that was a very important kind of stepping-stone for me.”

Weider, who became interested in Napoleon because of the French emperor’s role in freeing the Jews of Europe, owned a shirt of Napoleon’s made by a Jewish tailor who had put a Magen David onto one of the buttons as a tribute to him. He also owned several locks of Napoleon’s hair, which he had forensically tested. The results led him to conclude that Napoleon had been murdered by arsenic poisoning, a hypothesis he explored in a bestselling book, The Murder of Napoleon, which appeared in 1982. He received the French Legion d’honneur for his historical writings, and was also the recipient of the Order of Canada, l’ordre du Quebec and many other honours.

Until he donated his collection to the museum, Weider’s office was filled with his beloved Napoleonic collection. “When you walked into his office, it was like walking into the imperial presence — there were huge oils of Napoleon and busts of Napoleon everywhere you looked,” Joe King said.

Until he donated his collection to the museum, Weider’s office was filled with his beloved Napoleonic collection. “When you walked into his office, it was like walking into the imperial presence — there were huge oils of Napoleon and busts of Napoleon everywhere you looked,” Joe King said.

“Ben’s life was full and his years crowded with achievements that touched all kinds of people,” said Rabbi Alan Bright at the funeral. There were more than 1,000 mourners in attendance, including former Quebec premier Lucien Bouchard, Roman Catholic Cardinal Jean-Claude Turcotte, and former speaker of the Quebec National Assembly Michel Bissonnet. Many representatives of Montreal’s Jewish community, which Weider had helped philanthropically, were also present.

Weidere was born November 29, 1923 in Montreal and died October 17, 2008, leaving behind his wife Huguette, sons Louis, Eric and Mark, and siblings Joe and Freda. ♦

Appeared originally in the London Jewish Chronicle. © 2008