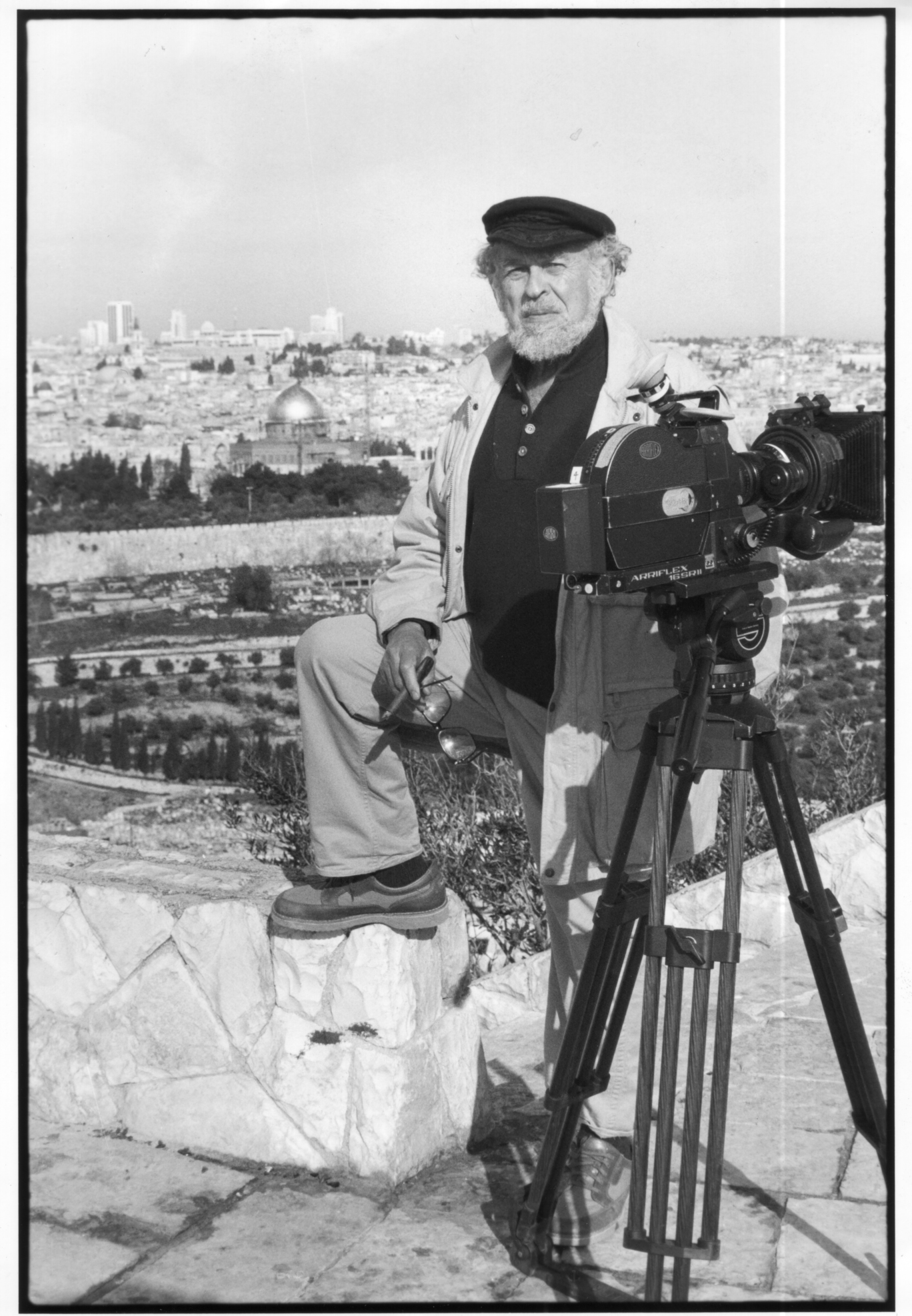

Known for his award-winning cinematic portraits of such iconic artists as Marc Chagall, Tennessee Williams, Leonard Cohen, Henry Moore, Yousuf Karsh, Arthur Miller and George Bernard Shaw, Toronto-based documentary filmmaker Harry Rasky has died in Toronto at age 78.

Known for his award-winning cinematic portraits of such iconic artists as Marc Chagall, Tennessee Williams, Leonard Cohen, Henry Moore, Yousuf Karsh, Arthur Miller and George Bernard Shaw, Toronto-based documentary filmmaker Harry Rasky has died in Toronto at age 78.

A co-founder of the news-documentary department of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, Rasky made more than 50 feature documentaries and hundreds of TV documentaries over a career that spanned half a century and began with a job as reporter for the Northern Daily News in Kirkland Lake, Ont.

In addition to two Oscar nominations, his films brought him a bouquet of Emmy, Genie, Peabody, and other awards and honours — so many that the Denver International Film Festival once called him “the world’s most acclaimed non-fiction filmmaker.”

Rasky remained good friends with many of the subjects of his films, several of whom pronounced that he had captured their genuine selves on celluloid. As he explained it, part of the artistic process for him involved an intense identification with each personality that he profiled.

“Somehow my own life became more and more reflected in the subject material” of his films, he wrote in Nobody Swings on Sunday, a 1980 autobiography. In The Three Harrys, a second memoir published in 1999, he added, “All the lives I have written about [or explored on film] are mine, as mine is theirs.”

His 1977 film Homage to Chagall: The Colours of Love, an intimate portrait of the legendary artist that highlighted his magnificent art and his devotion to his Jewish heritage, received international acclaim and an invitation to Rasky to attend a screening of the film at the Moscow Film Festival.

The film received “a stunning standing ovation that went on for some minutes,” he recalled. “I felt in a way that my work had been finally, really understood.”

Many Jews who saw the film were so touched by its portrayal of Chagall’s attachment to Judaism that they were reduced to weeping, Rasky recalled. Chagall too was enthralled by the film, which he said “will help me live longer.”

Although Rasky had traveled to some 50 countries, he regarded that trip to Russia as a homecoming of a sort.

The Pobberegesky family came from Desha, a village near Kiev, and crossed the Atlantic on a steamship passage arranged by the well-known Dworkin Agency of Toronto: the name was shortened to Rasky soon after landing. Harry (Elchanan), one of five sons and three daughters of Leib and Pearl Rasky, was born in Toronto in 1928. The family lived on St. Clair Avenue West.

Back in the dirty thirties, his father, Leib Rasky, sang in the small synagogue on MacKay Street. A shoichet, he purchased live chickens in Kensington market for kosher slaughter and resale. As the children grew up, they routinely delivered chickens around the neighbourhood and further afield by wagon and bicycle.

“The community was mostly English and Irish, enormously Protestant, enormously proud and enormously prejudiced,” Rasky recalled in Nobody Swings on Sunday, an autobiographical documentary (2003) that focused on his childhood neighbourhood and the straitlaced and often antisemitic society in which he grew up.

After graduating from Oakwood Collegiate and the University of Toronto, he left his old neighbourhood for good, and later moved with his family into what he would call “the ultra-WASP bastion of Rosedale.” But in his heart he never left the colourful streets of his childhood, nor his Jewish heritage.

He often explored Jewish subjects and themes in his works, as in The Spies Who Never Were (1982) which told the story of Jewish refugees interned in Canada during wartime; and To Mend the World (1987), which presented a view of the Holocaust based on the work of artists such as Gershon Iskowitz.

Song of Leonard Cohen (1981) was applauded for capturing the remarkable rapport between Montreal poets Leonard Cohen and Irving Layton; while The Man Who Hid Anne Frank (1980) focused on Victor Kugler, and Prophecy (1994) spotlighted Rabbi Chaim Nussbaum, wartime chaplain on the River Kwai.

Described as a “poet with a camera,” Rasky profiled many artistic personalities besides Chagall, as evidenced by his films on Mikhail Baryshnikov, Edgar Degas, Raymond Massey, Henry Moore, Yousef Karsh, William Hutt and Amedeo Modigliani.

His filmography also includes “literary” appreciations of George Bernard Shaw, Stephen Leacock, Tennessee Williams, Arthur Miller, Northrop Frye and Robertson Davies. His 1995 documentary The War Against the Indians: The Dispossessed, was one of several titles that probed into history.

Rasky died April 9, leaving behind his wife Arlene, and children Holly and Adam.

“He was one of the two or three most important documentary filmmakers Canada ever produced,” said Mark Starowicz, head of CBC-TV’s documentary programming unit. ♦

© 2007