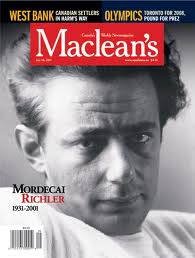

Mordecai Richler, the acclaimed Canadian novelist who died July 3, 2001 at the age of 70, will be remembered for his various novels that brought the Jewish life of Montreal to vibrant and often hilarious life on the page.

Mordecai Richler, the acclaimed Canadian novelist who died July 3, 2001 at the age of 70, will be remembered for his various novels that brought the Jewish life of Montreal to vibrant and often hilarious life on the page.

An irreverent satirist who honed his wit on diverse targets from the Jews to Quebec’s protective language laws, Richler wrote a handful of novels set in Jewish Montreal, including The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz (1959), St. Urbain’s Horseman (1971), Joshua Then and Now (1980), Solomon Gursky was Here (1989) and Barney’s Version (1997).

He once said that his goal was “to be an honest witness to my time and my place, and to write at least one novel that will last, that will be read after death. So I’m compelled to keep trying.”

The son of an immigrant junkdealer and the grandson of a rabbi, Richler abandoned his family’s Orthodox ways as a teenager. In 1954, at the age of 23, his aspiration to become a writer led him to leave his native Montreal for London, where he lived for nearly 20 years, achieving success as a novelist and scriptwriter for television and films.

But the expatriate Quebecker could never forget his ties to his native country and city, to which he returned in 1972. “No matter how long I continue to live abroad, I do feel forever rooted in Montreal’s St. Urbain Street,” he said. “That was my time, my place, and I have elected myself to get it right.”

Besides ten novels, he wrote three popular children’s books and several books of essays; On Snooker, a non-fiction book, is slated for publication in August. A consummate magazine journalist, he wrote pieces for publications as diverse as Playboy, Commentary, Saturday Night, The Spectator, GQ and The New Yorker. Until a few weeks ago he wrote a cherished weekly column for Conrad Black’s Toronto newspaper, the National Post.

Besides ten novels, he wrote three popular children’s books and several books of essays; On Snooker, a non-fiction book, is slated for publication in August. A consummate magazine journalist, he wrote pieces for publications as diverse as Playboy, Commentary, Saturday Night, The Spectator, GQ and The New Yorker. Until a few weeks ago he wrote a cherished weekly column for Conrad Black’s Toronto newspaper, the National Post.

Richler, an equal-opportunity offender, was the bane of many an editor’s existence; having succeeded on his own terms, he kowtowed to no one. He once flew from London to Ottawa to cover a major football game for the Canadian newsmagazine Macleans. However, the weather was so cold that he stayed in his hotel room and watched the game on television. Twice nominated for Britain’s prestigious Booker Prize, he won two Canadian Governor General Awards and Canada’s $25,000 Giller Prize (for Barney’s Version). He was the focus of an evening of tribute in Toronto last fall, and received the Order of Canada in the spring.

Film director Ted Kotcheff, who brought The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz to the screen, shared a flat with Richler in his early London days, and recalls his rigid routine — typing on an old Olivetti daily from 9 to noon, then from 2 to 5 in the afternoon. “If I waited for inspiration to strike I’d never write a single bloody word,” Richler had explained.

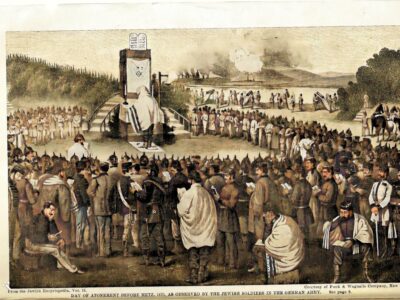

For many readers, Richler was their entree to a delectible and funny world of bagels, bar mitzvahs, shvitz baths, smoked meat and other things Jewish. Toronto writer Barbara Gowdy, a self-described “WASP”, says her father adored Richler and would be transformed after reading one of his novels. “He would speak to us kids in a Yiddish accent and refer to us as ‘goys.’ He would say, ‘As there is only one Madonna and only one God, there is only one Mordecai.'”

Saskatchewan novelist Guy Vanderhaege says he took inspiration from Richler’s vivid portrait of Montreal Jewish society. “If Mordecai Richler could make an obscure street in Montreal so vibrantly alive in my imagination, just maybe I could do the same with my piece of territory.”

Saskatchewan novelist Guy Vanderhaege says he took inspiration from Richler’s vivid portrait of Montreal Jewish society. “If Mordecai Richler could make an obscure street in Montreal so vibrantly alive in my imagination, just maybe I could do the same with my piece of territory.”

Richler had a cancerous kidney removed in 1998 and was considered recovered until recently when the disease was discovered in his other kidney. He leaves his wife of 40 years, Florence Wood, and their five children, Daniel, Noah, Emma, Martha and Jacob. ♦

© 2001

RICHLER FETED AT INTERNATIONAL FESTIVAL OF AUTHORS (October 2000)

Canada’s most prestigious literary festival, the Toronto-based Harbourfront International Festival of Authors, opened its 21st season in late October with an evening in tribute to Montreal Jewish author Mordecai Richler, famous for such novels as The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz, St. Urbain’s Horseman, Solomon Gursky Was Here and Barney’s Version.

A paying audience of hundreds of people listened with approval as a roster of well-known Canadians variously roasted and toasted Richler, who published his first novel in 1954 when he was 23 years old, and who turns 70 in January.

Film director Ted Kotcheff recounted episodes from his long friendship with the writer, including scenes from their days when they roomed together in London in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Richler’s routine was rigid, Kotcheff recalled. Each day, he typed on an old Olivetti solidly from 9 to noon, then from 2 to 5 in the afternoon. “If I waited for inspiration to strike I’d never write a single bloody word,” Richler had explained.

Kotcheff recalled a memorable exchange between Richler and Saidye Bronfman, the wife of Seagram’s magnate Sam Bronfman, at the world premiere of the Kotcheff-directed film The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz in Montreal.

“Well, Mordecai,” Mrs. Bronfman reportedly congratulated Richler, “you’ve come a long way from being a St. Urbain Street slum boy.”

“Well, Saidye,” Richler reportedly replied, with his famous cutting wit, “you’ve come a long way from being a bootlegger’s wife.”

“Like Queen Victoria, she was not amused,” Kotcheff recalled.

As several speakers observed, Richler gave his many readers an ironic and irresistibly funny picture of Jewish life as lived in the old ghetto of downtown Montreal.

Toronto writer Barbara Gowdy, a self-identified “WASP”, said that her father adored Richler and would be transformed after reading one of his novels. “He would speak to us kids in a Yiddish accent and refer to us as ‘goys,'” she said. “He would say, ‘As there is only one Madonna and only one God, there is only one Mordecai.”

Saskatchewan novelist Guy Vanderhaege said that he found inspiration in Richler’s vivid portrait of Montreal Jewish society. “If Mordecai Richler could make an obscure street in Montreal so vibrantly alive in my imagination, just maybe I could do the same with my piece of territory.”

One speaker recalled that Richler once flew from London to Ottawa on assignment for the Canadian newsmagazine Maclean’s, which wanted him to cover a major football game. As Richler freely admitted in his article, the weather was so cold that he stayed in his hotel room and watched the game on television.

Robert McNeill, the retired American broadcaster, said that Richler’s return to Canada from London in the 1970s was an important symbol of confidence to the cultural community here from one who had learned “it was easier to make a reputation outside of Canada than within it.”

“There is no other voice in Canadian literature like Richler’s,” he said. “I devoured his books with joy. They were books that explored Canadian identity in a bawdy, delicious way.”

After more than an hour of such lavish tributes, Richler himself took the stage. “I don’t know how the rest of you feel,” he said, “but this evening’s program struck me as being awfully short.” ♦

Originally appeared in the London Jewish Chronicle. © 2000