Dorothy Macham, a former army nurse who received an Associate Royal Red Cross medal from King George VI and headed Women’s College Hospital for three decades, died in Toronto in July, one week shy of her 92nd birthday.

Dorothy Macham, a former army nurse who received an Associate Royal Red Cross medal from King George VI and headed Women’s College Hospital for three decades, died in Toronto in July, one week shy of her 92nd birthday.

Ms. Macham had several years of operating room experience when she joined the Canadian Army Medical Corps at the outbreak of the Second World War. She served bravely with Canadian mobile hospital units in England, Italy, France, Belgium and Holland, often directly behind the front lines. She became a major, a rank rarely accorded to women, and won numerous military awards and ribbons.

Once asked if her military service had been anything like the MASH television show, she replied, “Yes, but without the jokes.” She rarely spoke of her wartime experiences but told a friend after the events of last Sept. 11, “I have seen even worse things.”

Dorothy Ann Macham, nursing sister and hospital administrator. Born in New Lowell, Simcoe County, Ont. on July 19, 1910. Died in Toronto, July 12, 2002.

Joining Women’s College in January 1946, she ushered the hospital through a period of growth and transformation during which it tripled in size to become a 450-bed teaching institution. She was known as an efficient, thrifty administrator who exerted a spirit of gentleness and compassion throughout the hospital corridors.

“She was the hospital, and the atmosphere of the place was her, basically,” said Dr. Donald Moore. “It was a pleasant place to work and a lot of it had to do with Dorothy and the atmosphere she created.”

Leaving Women’s College in 1975, she became executive director of Toronto’s West Park Hospital, which she also guided through a major expansion before retiring in 1979. She won a City of Toronto Merit Award in 1976 and was named to the Order of Canada in 1980.

She was born in 1910 on the farm in Simcoe County that her grandparents had settled half a century earlier. As a child, she was inspired by a nurse who used to visit and by a great-aunt who worked as a Methodist missionary in Morocco; her dream was to become either a nurse or a missionary.

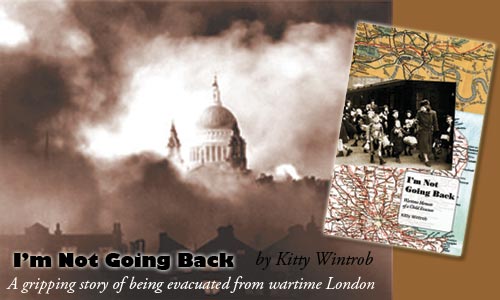

She enrolled in Women’s College Hospital School of Nursing in 1929, graduated in 1932, and worked as assistant supervisor in the hospital’s operating room. She enlisted on September 10, 1939, one week after war was declared, and left for England in June 1940. She served with Canadian medical units in Bramshott Chase, Basingstoke and Copthorne, treating illnesses, burns, broken jaws and other injuries requiring plastic surgery.

She enrolled in Women’s College Hospital School of Nursing in 1929, graduated in 1932, and worked as assistant supervisor in the hospital’s operating room. She enlisted on September 10, 1939, one week after war was declared, and left for England in June 1940. She served with Canadian medical units in Bramshott Chase, Basingstoke and Copthorne, treating illnesses, burns, broken jaws and other injuries requiring plastic surgery.

In October 1943 she boarded a large American troop ship at Liverpool that was part of a convoy of 30 ships and several destroyers, only learning at sea that her destination was Sicily. The ships passed through the Straight of Gibraltar in single file, which “was an awesome sight as it was at sundown and the Rock glowed red,” she would write in a war memoir. After dark one ship was attacked by air and sank, but all personnel were rescued.

Moving from Sicily into Italy and then up the Adriatic coast, she and her medical unit lived under canvas just behind the Allied offensive. “We were able to see the flashes, the sky was really lit up,” she writes of a nocturnal barrage of shelling near Mount Cassino. “In the early morning, about 6 a.m., many bombers flew over. I pulled my cot out of my tent and lay there and watched wave after wave of planes go over.”

She was shipped back to England in mid-1944 and then to France, where she joined No. 8 Canadian General Hospital. “The nights were disturbed by the ack ack guns; shrapnel fell around, some cutting through our tents.” Conditions were equally rough and casualties equally heavy in Belgium and Holland. She returned to England in March 1945 and was posted to several Canadian mobile medical units in succession.

In July she attended an investiture ceremony at Buckingham Palace in which King George VI pinned a medal on her. Afterwards she lunched with friends at the posh Dorchester Hotel. She was still tending the sick and wounded when Women’s College cabled to offer her the post of hospital superintendant. “Can’t be relieved at present time,” she wired back. The hospital waited for her.

In her early years at Women’s College, she would sit in her office in full nursing uniform, with the door open: “The message was clear — I am in charge but willing to hear about your problems,” one colleague recalled.

“She knew exactly what was going on everywhere in the hospital, whether it was with the patients or staff,” said Dr. F. Marguerite Hill.

Established in 1883 to give female doctors a place to work, Women’s College had to accept male physicians onto its staff to become a University of Toronto affiliate in 1961. “A battle royal raged over the very idea that the hen house would be invaded by doctors in pants,” Dr. Joan Vale recalled. Ms. Macham championed the change and persuaded many staff members that it would be for the best.

She welcomed numerous dignitaries to ribbon-cutting ceremonies, including the Queen Mother and Prime Minister Trudeau. Always budget-conscious, she helped to found a joint laundry service for the downtown hospitals and once flew to Ottawa to expedite a crucially-needed tax refund. A dedicated fundraiser, she was once offered $100 to fall into a pool at a social benefit for the hospital in a wealthy patron’s backyard. The hospital got the money.

Alan Dorman, a former West Park executive, is one of many of Ms. Macham’s associates to cite her as a memorable influence. “I probably learned more in the five years that I worked for Dorothy than I did with anybody else that I worked for — and I worked for some very senior hospital presidents,” he said. Sunnybrook and Women’s College Hospital named a veterans’ facility in her honour last year. West Park also named a day-patient wing for her.

A former president of the Nursing Sisters Association of Canada and a longtime member of the Metropolitan United Church, she became a zealous genealogist and traveler in her retirement years. Perhaps her most adventurous trip was a three-month journey by air and sea with a friend to New Zealand, from which she returned by cargo freighter to New Orleans.

She never married. She was predeceased by a sister before birth and by brother Douglas in 1961. A brother, Howard, died on Aug. 6, 2002, aged 95. She is survived by sister Edith, aged 98, of Ottawa, and by seven nieces and nephews. ♦

© 2002