From the Globe and Mail, 2003

From the Globe and Mail, 2003

E. B. Cox, a much-admired Toronto-area sculptor who prided himself on achieving artistic and commercial success without ever taking a penny in government grants, died last summer at the age of 89.

E. B. was a young associate of some of the Group of Seven with whom he went on northern sketching trips; A. Y. Jackson once complimented him on his “good sense of form.” He later carved their tombstone epitaphs.

A wood carver from a young age, he came to master stone and even the delicate art of faceting and carving precious stones; he also tried metal, ceramics and glass. Because he liked to work fast, he pioneered the use of power tools to quicken the chiseling process, a technique that purists initially regarded as a form of cheating.

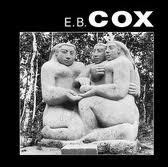

According to one guidebook, E. B. Cox has “more sculpture on view in Toronto’s public places than any other single artist.” His 20-piece Garden of the Greek Gods, originally installed in the ’50s on the Georgian Peaks near Collingwood, Ont., was later relocated to the far more populous grounds of the Canadian National Exhibition near the Dufferin Gate. The only fully human representation in the group, an 11-foot-high statue of Hercules, was carved from a six-ton piece of Indiana limestone — “the biggest piece of stone used by a sculptor in Canada,” according to friend and patron, Ken Smith.

Among his many other public works are a fish fountain for an outdoor courtyard at the former Park Plaza Hotel, a stone bear for the Guild Inn, a stone Orpheus for Victoria College, lavish countertops and railings for historic bank buildings, a large seated lady for McMaster University and whimsical creatures for a schoolyard in Milton, Ont.

Among his many other public works are a fish fountain for an outdoor courtyard at the former Park Plaza Hotel, a stone bear for the Guild Inn, a stone Orpheus for Victoria College, lavish countertops and railings for historic bank buildings, a large seated lady for McMaster University and whimsical creatures for a schoolyard in Milton, Ont.

Having mastered big, he also excelled in small: he used to claim that he invented coffee-table art. He carved little totem poles to put himself through university, and became known for his small bear sculptures, which he sold at popular prices especially at Christmas. “At university I damned near starved,” he would explain. “I don’t believe in starving artists.”

Influenced by Iroquois and west-coast Haida art, he focused on bears, beavers, birds and other animals as well as human torsos, masks and heads; he often caught the animals in quirky fluid poses that never failed to capture their essential natures. He once crafted an all-Canadian limited-edition chess set for the Hudsons Bay Company, with beavers as pawns, couriers-du-bois as knights, Indian princesses as queens, and so on. He was “the great bridge between aboriginal art and modern art,” according to Smith and others. A picture-book about him, featuring an essay by Gary Michael Dault, was published by Boston Mills Press in 1999.

“He was entirely original,” said Toronto sculptor Dora de Pedery-Hunt. “Absolutely nobody else did what he did. What style he had was entirely his. I call him a real good sculptor, a real good artist.”

The younger of two brothers, Elford Bradley Cox was born on July 16, 1914, in Botha, Alta., where his family made a short-lived attempt at farming; he learned to carve by watching his maternal grandfather whittle kindling by the fireside; he persisted in sculpting even though his pious father was vehemently opposed to the creation of “graven images,” he told Toronto Life magazine in 1997. The family returned to Bowmanville, Ont., where E. B. spent most of his childhood, and where his mother died suddenly after an epileptic attack when her favoured son was a young teenager. When it was time for him to go to university, “his father sent him off with five dollars, a suitcase, and a wish of good luck,” said Kathy Sutton, the younger of his two daughters.

The younger of two brothers, Elford Bradley Cox was born on July 16, 1914, in Botha, Alta., where his family made a short-lived attempt at farming; he learned to carve by watching his maternal grandfather whittle kindling by the fireside; he persisted in sculpting even though his pious father was vehemently opposed to the creation of “graven images,” he told Toronto Life magazine in 1997. The family returned to Bowmanville, Ont., where E. B. spent most of his childhood, and where his mother died suddenly after an epileptic attack when her favoured son was a young teenager. When it was time for him to go to university, “his father sent him off with five dollars, a suitcase, and a wish of good luck,” said Kathy Sutton, the younger of his two daughters.

Studying languages at the University of Toronto from 1934 to 1938, E.B. was befriended by German professor and painter Barker Fairley, who introduced him to A.Y. Jackson, Fred Varley and Arthur Lismer of the Group of Seven. E.B. started teaching languages at Upper Canada College, but soon left to join the war effort as an intelligence officer, interrogating prisoners of war in Europe. Afterwards he resumed teaching at UCC, and devoted part of a summer to a school canoe trip on the Mississauga River; the next summer he escorted a group of boys on an even more adventurous trip down the Churchill River in the Barren-lands. “That was just unheard-of in those years,” recalled Terence A. Wardrop, who joined that expedition and became E.B.’s lifelong friend and solicitor. “It was a big trip and it was almost historic — the rivers and some of the lakes were unmapped in 1948.”

Quitting his teaching job in 1949, E.B. married the former Betty Campbell, bought a farm near Palgrave, Ont. and discovered he could survive as a full-time artist. (Although he considered government subsidies poisonous, he once applied for a government grant to study Canadian stones suitable for sculpting — and was turned down. “I did my stone research without their damn-fool money,” he told the Globe and Mail in 1970.)

Moving to a rural property in north Toronto and later to a Victorian house in eastern Toronto, he affected an amicable separation from his wife. Being partial to pranks, he once purchased a canoe for her as a gift and paddled it to the dock at the family cottage in a rented disguise to achieve maximum surprise. Along with his love of humour, friends recall his sharp wit and his ability to cut through social pretense. “He said he wanted his gravestone to read, ‘I told you I was sick,'” recalled art dealer John Ingram. “That’s what I remember about him — his great sense of humour and just what a wonderful compassionate guy he was. He tried to give this air of being an old curmudgeon but in fact, he was anything but.”

Becoming a mentor to many young artists, E. B. generously shared his tools and experience with them. “He didn’t have much mentoring when he was learning to be an artist — people didn’t help him — so he took the opposite tack,” said daughter Kathy. Always enthusiatic and full of ideas, he was usually in his workshop early in the morning — and kept on working even after losing his sight in his final years. His home was full of fine sculpture and painting, including a portrait of E.B. by Fairley that hung over the mantel. “It was a lovely place, and by the time you got out of there, you were in a buying fever,” Smith recalled. “E.B. himself was part of the fun of buying stuff. People were just charmed by the atmosphere he created.” He was also famously not particular about the prices he asked from genuine admirers of his work.

As for his art’s place in the world, he was confident it would last, at least in the physical sense. “We’d have these long philosophical talks about whether there was an afterlife and what legacy to leave behind,” friend Eric Conroy recalled. “He’d say that his stone works would be there long after Rembrandt’s paintings had crumbled.”

E.B. Cox died in Toronto on July 29, 2003, leaving behind wife Betty, daughters Sally Sproule and Kathy Sutton, two grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. ♦

© 2003