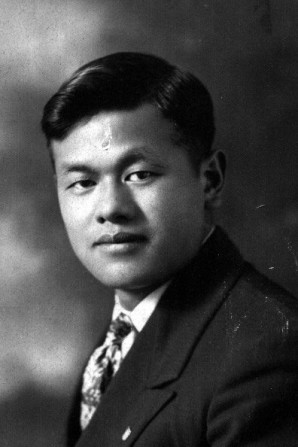

Kew Dock Yip, a familiar and distinguished figure in Toronto’s Chinatown for more than half a century, has died in Toronto at the age of 94.

Kew Dock Yip, a familiar and distinguished figure in Toronto’s Chinatown for more than half a century, has died in Toronto at the age of 94.

While serving as a reserve in the Queen’s Own Rifles in 1942, Mr. Yip entered Osgoode Hall Law School and in 1945 became the first lawyer of Asian descent in Canada.

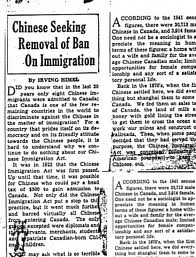

In 1947 he played a pivotal role in persuading the federal government to repeal the Chinese Immigration Act, also known as the Chinese Exclusion Act, which effectively opened the doors for Chinese immigration to Canada. (Toronto lawyer Irving Himel, who worked closely with Mr. Yip to repeal the legislation, also died this month; see obituary, below.)

“He had a vision of Canada as an equal opportunity land where everybody had a chance,” said Lin Yip, his daughter-in-law. “He believed in an equitable Canada, a fair Canada.”

For many years Mr. Yip was “the only Chinese-speaking lawyer in Chinatown,” said Alfie Yip, his son. He maintained a storefront on Toronto’s Elizabeth Street for nearly four decades before moving his sole practice to an office at Dundas and Bay in 1985.

An old-style lawyer who didn’t bother with time dockets, he “gave personal care and attention to his clients,” said lawyer Gary Lloyd Gottlieb, a bencher of the Law Society of Upper Canada.

“He was just down the hall from my office, and I used to spend a lot of time talking to him, not merely about the law but about life. He was a person of integrity and the best role model that a younger lawyer could ever have.”

A strong advocate of education, he served two terms as a school board trustee in Ward 6 in the 1970s, and impressed people with his wide knowledge and diverse range of interests. “He was like a talking history book to his grandchildren,” said Mrs. Yip, noting her father-in-law’s expertise in Canadian, American and Chinese history.

“Dock could just as easily talk about Macauley, Dickens and Robert Louis Stevenson as he could about Coke and Blackstone, the commentators on English common law,” Mr. Gottlieb said.

As a septuagenarian Mr. Yip took a correspondence course in Shakespearean English. He also took up acting and landed a role in the movie Year of the Dragon. The Law Society of Upper Canada awarded him its Law Society Medal in 1998.

Born in Vancouver to Cantonese parents in 1906, he was the 17th of 19 sons. His father, Yip Wang Sang, had 23 children by four wives, establishing such a large and complex family tree that for simplicity’s sake, Mr. Yip’s many nephews and nieces often referred to him as Uncle Number 17. A patriarch of Vancouver’s Chinatown, Yip Wang Sang was a paymaster for the CPR and an acknowledged pioneer of Canada whose portrait hangs on Parliament Hill.

Mr. Yip earned a degree in pharmacology from the University of Michigan in 1931 but never used it. He worked as a secretary in the Chinese consulate in Vancouver in the 1930s and came to Toronto about 1940. He married his childhood sweetheart, Victoria Chow, in 1942.

His vision of Canada as a land of equality and opportunity is perhaps best reflected in his response to a friend who asked why he was studying law when Chinese were not allowed to practice law in Canada. “Yes, that is true,” he replied. “But I am not Chinese. I am a Canadian, and so are you.”

He is survived by his wife, sons Alfred, Duncan James and Malcolm John, and five grandchildren. ♦

© 2001. First appeared in the Globe and Mail

IRVING HIMEL (1915-2001)

Toronto solicitor Irving Himel, a champion of civil liberties and human rights, has died recently in Toronto at the age of 86.

A passionate defender of minority rights, he helped change federal and provincial laws in several key areas between the end of the Second World War and the enshrinement of the Canadian Charter of Rights in 1982.

He was an energetic legal crusader who orchestrated lobby groups, wrote articles and letters, and launched court actions in order to fight injustice.

He was an energetic legal crusader who orchestrated lobby groups, wrote articles and letters, and launched court actions in order to fight injustice.

“Our commandment in the Bible is ‘Justice, justice, shalt thou pursue,’ and Irving exemplified that,” said his brother, Sydney Himel. “All his life he sought justice for all people.”

When Mr. Himel took aim in the late 1950s against restrictive covenants — the discriminatory clauses inserted in real estate deeds that prevent owners from selling to Jews and other perceived undesirables — the result was an important legal decision that knocked them down. He also helped to change discriminatory rental practises of hotels and resorts.

Paralleling his status in the Jewish community, Mr. Himel was also a hero to Canada’s Chinese community. Together with Kew Dock Yip, a lawyer whom he had known at Osgoode Hall Law School, he successfully lobbied the government in 1947 to repeal the Chinese Immigration Act (a.k.a. the Chinese Exclusion Act), which barred Chinese immigrants from entering Canada. (Coincidentally, Mr. Yip predeceased Mr. Himel by a week; see obituary, above.)

Mr. Himel helped persuade the government to enact the Fair Employment and Practices Act, which outlaws discrimination in the workplace. He stood on the side of labour and represented the clothing, seamen’s, police and other unions. He was a founding member of the Canadian Civil Liberties Association and its executive secretary for many years.

Born in 1915 in a Jewish neighbourhood in the Dundas-Spadina section of Toronto, he was the middle of five children of Russian-Jewish immigrant parents. His father was a shopkeeper. He went to Jarvis Collegiate and the University of Toronto. While in law school in the late 1930s, he won $100 in an essay contest. The prize went to cover a critical shortfall in his tuition.

No stranger to discrimination, he became a passionate advocate for all victims of racial, religious and other forms of prejudice. “That was part of what made him the way he was, and it was why he went into law,” said his son, Richard Himel. “It was part of his character.”

“The remarkable thing is that he began doing these things in the 1940s,” said Himel’s friend, solicitor Bert Raphael. “In a sense, it’s much easier to be a human rights activist now, because we’ve got the Bill of Rights and the human rights commissions to protect us.”

Mr. Himel leaves his wife Evelyn, son Richard, grandson David, brother Sydney, and numerous nieces and nephews. ♦

© 2001. First appeared in the Globe and Mail