We left Aqaba at dawn. Squat buildings and palm trees receded into the desert behind us as our jeep spat up clouds of dust.

We left Aqaba at dawn. Squat buildings and palm trees receded into the desert behind us as our jeep spat up clouds of dust.

Travelling the King’s Highway, we reached Petra in two hours, and took a light breakfast at the Petra Forum, a local hotel. Afterwards, we hired two fine horses — Ruba a noble white steed, myself a sturdy roan and penetrated the mouth of the Siq, the serpentine arroyo or canyon that winds into the ancient city.

A trained guide, Ruba had been here many times before. Still, she seemed as awed as I, entering Petra for the first time. We rode in silence as the Siq became steeper and narrower around us. While most of the trail was in shadow, sunlight capriciously brightened patches of the colourful rock and danced in quivering patches on the ground. High above us, desert thickets protruded from the craggy rocks.

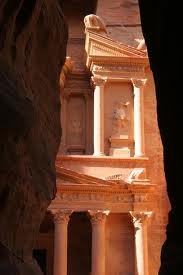

For almost three quarters of an hour, the grating of horses’ hooves on rock was practically the only sound we heard. Rounding a final bend, we confronted an astonishing sight: the towering and majestic facade of the Treasury, an architecturally splendid building carved into solid rock. At this point the Siq opens into a broad plaza, beyond which lies a city of 10,000 rock hewn dwellings. The builders were the Nabateans, a reclusive Biblical era tribe, and the Romans who conquered them.

What made the site so desirable to both the Nabateans and the Romans is its seclusion. Strange and vast, this unique metropolis is ringed by mostly impenetrable mountains. Lost to Western travellers since the Crusades, rediscovered by a Swiss explorer in 1812, Petra is considered one of the wonders of the ancient world.

As in centuries past, the only way of getting into Petra is on foot, horse, camel or donkey cart. Since the Israel Jordan peace agreement of 1994, more than 100,000 Israelis and probably many more foreign tourists in Israel have crossed the newly opened border into Jordan, and most have visited Petra.

It has been only in the last half century or less that the city has become accessible to sightseers. Before then, bedouins camping in the stone dwellings would often greet travellers with rifle fire. No one lives in Petra anymore, Ruba told me. Several years ago, the government declared the site a national archaeological treasure and transferred its inhabitants to a nearby village.

It has been only in the last half century or less that the city has become accessible to sightseers. Before then, bedouins camping in the stone dwellings would often greet travellers with rifle fire. No one lives in Petra anymore, Ruba told me. Several years ago, the government declared the site a national archaeological treasure and transferred its inhabitants to a nearby village.

We inspected the monumental ruins for a couple of hours. When the sun became merciless, we ducked into a large rock chamber that had once probably been someone’s living room: it was dark and chilly inside. To our surprise, a bedouin boy had fashioned the ancient cubicle into a tiny variety shop. We bought two Pepsis in old fashioned six ounce bottles.

Re emerging into daylight, we spotted a stout elderly bedouin woman, sipping tea. She was dressed all in black and sitting on a rock in the shade of some dwarfish trees. Ruba seemed to recognize her at once. “Did I say there were no more Bedouins living here anymore? No, that was wrong. She’s the only one.”

The Old Woman of Petra looked possibly six hundred years of age. She seemed somehow to embody all the old mysterious ways that live on in the Arabian desert. Her face was wrinkled and tattoed, her head kerchiefed, her teeth rotten, her black eyes reflecting an ineffable knowledge. Ruba spoke with her a moment in Arabic.

“She lives here all alone,” she told me as we walked away. “The rest of her tribe accepted the government relocation, leaving her behind. She says that Petra is her home and she doesn’t want to leave.”

“She lives here all alone,” she told me as we walked away. “The rest of her tribe accepted the government relocation, leaving her behind. She says that Petra is her home and she doesn’t want to leave.”

A further revelation dispossessed me of the naive assumption that the old woman, living without modern conveniences, would know little of civilization beyond this petrified desert world. She had surprised Ruba by asking about of all things the performance of certain commodities on the New York stock market.

As Ruba explained, the woman’s son had married a Swiss woman and had gone to work for a bank in Zurich. “She’s hoping his investments do well so that he can afford to bring her grandchildren here for a visit.” ♦

© 2002