Alexander Beider, who is arguably the world’s foremost expert on Jewish names, has revised and updated his 1993 Dictionary of Jewish Surnames from the Russian Empire, a four-year task that he undertook knowing it would probably not generate adequate renumeration for him. If that proves to be the case, he may yet take comfort in knowing that his latest Herculean labour will probably prove of enduring benefit to those of us with Jewish roots in the former Pale of Settlement and various adjoining territories. This is the best such book ever produced, and will likely retain that title for many years to come.

Alexander Beider, who is arguably the world’s foremost expert on Jewish names, has revised and updated his 1993 Dictionary of Jewish Surnames from the Russian Empire, a four-year task that he undertook knowing it would probably not generate adequate renumeration for him. If that proves to be the case, he may yet take comfort in knowing that his latest Herculean labour will probably prove of enduring benefit to those of us with Jewish roots in the former Pale of Settlement and various adjoining territories. This is the best such book ever produced, and will likely retain that title for many years to come.

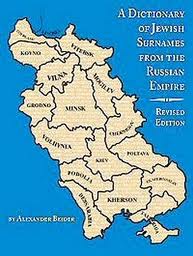

Hailed upon its first appearance, the Dictionary originally contained entries for about 50,000 surnames. Considerably heftier at 1,000 pages, the Revised Edition now boasts about 74,000 surname entries. The new edition reflects the explosion of new sources and knowledge that has occurred over the last 15 years due to the collapse of the Former Soviet Union, the rise of the Internet, the publication of numerous related new works, and other factors. Beider has altered hundreds of entries, expanded the geographical range of his survey, and added many new cross-references.

As before, the volume begins with six chapters on the history of Jewish names in Eastern Europe, their types and morphology, linguistic aspects, the patterns of their adoption in various regions, the coincidence of Jewish and Gentile surnames, and an explanation of Beider’s scientific approach. These chapters, which take up roughly 200 pages, are utterly fascinating but so densely written that they remind me of a tangled thicket in a fairy tale.

In the story, the prince hacks his way through the overgrown forest to reach the castle and the Sleeping Beauty within. Similarly, those who wish to look up the etymology of a surname may skip these challenging and highly technical opening sections and turn directly to the Dictionary of Surnames, which takes up the remaining 800 pages of the book. (A smaller softcover volume accompanies the Dictionary and provides an invaluable Soundex listing of all the surnames within.)

Beider, whose previous works include A Dictionary of Jewish Surnames from the Kingdom of Poland (1996) and A Dictionary of Jewish Surnames from Galicia (2004), has revolutionized the field of Jewish onomastics. The Moscow-born statistician, linguist and onomastician, who has lived in Paris since 1990, was the first researcher to do an inductive survey of Jewish surnames based exclusively on primary sources such as old voters’ lists, civil records and other archival documents. Most previous researchers had simply rehashed names and ideas from the published literature without a genuine scientific methodology.

Beider, whose previous works include A Dictionary of Jewish Surnames from the Kingdom of Poland (1996) and A Dictionary of Jewish Surnames from Galicia (2004), has revolutionized the field of Jewish onomastics. The Moscow-born statistician, linguist and onomastician, who has lived in Paris since 1990, was the first researcher to do an inductive survey of Jewish surnames based exclusively on primary sources such as old voters’ lists, civil records and other archival documents. Most previous researchers had simply rehashed names and ideas from the published literature without a genuine scientific methodology.

As he has explained in interviews, one of his most important innovations is his linkage of Jewish surnames with the geographical location and linguistic culture in which they first arose. The Dictionary abounds with examples of surnames derived from obscure place names or toponyms, codified with the letter (T). The name Bobrushkin is linked to the town of Bobrujsk, for instance, just as Drubicher is linked to to Drubich, Gordon to Grodno, Mogilevich to Mogilev, Polyakov to Polyak, Slobodkin to Slobodka, Usyshkin to the Usyskin River in Gorodok district.

Many such names have been changed or truncated beyond recognition, so it’s often useful to learn that a family name bears a reference to a once-beloved shtetl or Jewish village in the Old Country, even if the town may no longer be found on a map. (Those who wish to try locating an ancestral village should consult Gary Mokotoff and Sallyann Sack’s award-winning volume, Where Once We Walked.)

Browsing through the pages of Beider’s Dictionary makes one realize just how fully generations of life and experience are embedded into our surnames. Like nametags stitched by our mothers into items we are taking to summer camp, history seems stitched into our very names as though in preparation for a long and arduous journey. Many occupational (O) surnames, for example, provide glimpses of an outmoded village life of centuries past.

The name Bodgas, for instance, means “bathhouse” (from German); Cherednyak is “cattle shepherd” (Belarusian); Drach, “hand mill” (Yiddish); Fajnshrajber, “calligrapher” (Yiddish); Gitelmakher, “cap maker” (Yiddish); Goren, “forging furnace” (Ukrainian); Katsov, “butcher” (Hebrew); Latkemakher, “maker of pancakes” (Yiddish); Milkhiker, “dairyman” (German); Pakhter, “leaseholder” (Yiddish); Plytnik, “raft driver” (Belarusian); Rabin, “rabbi” (Ukrainian); Shkolnik, “beadle, sexton in a synagogue” (Belarusian); Torgovets, “tradesman” (Russian).

Again, many of these surnames did not survive the Holocaust or the process of immigration to the New World and the twin steamrollers of anglicization and Americanization. I once researched name-change files at the Archives of Ontario and found such metamorphoses as Cherkofsky to Chambers, Granofsky to Grant, Grodtizinsky to Gardner, Kestenberg to Keystone, Krawietz to Taylor, Muldofsky to Melvin, Persovsky to Pearson, Pokotolowsky to Lofsky, Rotenberg to Raymond, Tarnovsky to Turner, and Yarmolinsky to Yarmouth. Fortunately, the old names live on in the paper trail that our ancestors left behind.

As Beider notes, overlapping layers of meaning and language inevitably lend ambiguity and erode the exactitude of the science of surnames. Just one example: mightn’t Goren also refer to the Hebrew word for “threshing floor?” His discussion of such ambiguities are often illuminating and reveal a high fidelity to facts, which are never altered to fit theoretical constructs.

Other surname categories that Beider cites are artificial names (A); names derived from feminine (F) or masculine (M) given names; names of Kohen or Levite origin (K); names based on personal characteristics or a nickname (N); rabbinical (R) names; secondary (S) names; and names from regions outside of the compass of the book (Z). Surprises occur on every page, such as the link between the famous name of Chagall to the name Segal, a Kohenite acronym of Hebrew origin dating back to the 11th century.

Students of Jewish genealogy may want their own copies of A Dictionary of Jewish Surnames from the Russian Empire, Revised Edition; others may be content to consult it in a synagogue or reference library. The publisher is Avotaynu Inc. and the book may be ordered from the website www.avotaynu.com ♦

© 2009