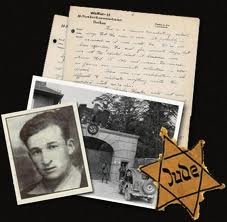

An international expert on German Jewish genealogy told a Toronto audience recently that the vast horde of Nazi records that the Americans confiscated from Germany after WWII has finally been catalogued, making the material much more accessible to genealogists and historians.

An international expert on German Jewish genealogy told a Toronto audience recently that the vast horde of Nazi records that the Americans confiscated from Germany after WWII has finally been catalogued, making the material much more accessible to genealogists and historians.

Peter Lande, who spoke to the Jewish Genealogical Society of Canada (Toronto) during Holocaust Education Week, said the material includes concentration and death camp records, deportation lists, and many other types of records.

What’s perhaps most impressive about the cataloguing feat is that Lande, a retired American diplomat who lives in Washington DC, did it all himself.

Most of the captured German records were microfilmed and returned to Germany in the 1950s. They take up 189 reels of microfilm, with 1,000 frames per reel. Lande said he examined every frame — 189,000 in total.

The microfilmed collection is housed at the US National Archives, with copies at a few other American research institutions and at Yad Vashem. The index will be available through the JewishGen web site, he said.

The collection includes many diverse Holocaust-era records — for example, a list of about 120,000 Dachau inmates and a much smaller list that enumerates residents of one town who were late paying their water bills. The reason they hadn’t paid was likely “because they’d been killed,” he said.

A longtime volunteer of the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, Lande was born in Germany and came to the United States with his family in the late 1930s. He has scoured many war-era collections looking for genealogically relevant material.

In recent years he has worked to put various Holocaust-related lists and films onto CD-ROMs for libraries and specialized research institutes worldwide. “Just think of all the collections that could be made available if this idea catches on,” he said.

He described another major project concerning the former Soviet Union’s Extraordinary State Commission into Nazi war crimes. Immediately after the war, a Soviet fact-finding body attempted to determine exactly what had happened in every locality within the Soviet orbit that had been occupied by the Nazis. The commission published its multi-volumed report in the late 1940s.

Yad Vashem microfilmed the collection in Moscow in 1990, and the US Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) possesses a copy; but the names of individual victims appear haphazardly, on a town-by-town basis. For the last few years, Lande said, the USHMM has paid keyboarders in St. Petersburg and Minsk to consolidate the names onto a computerized — and thus easily searchable — master list.

The keyboarders enter the names in cyrillic, and the marvels of technology take over from there, he said.

“We have a system whereby you push a button and it appears in Latin text on the same screen,” he said. “We’ve opened up an area that was basically inaccessible for 99 per cent of researchers.”

Lande told the CJN that he is motivated by the chance to help people find documentary evidence that might give them a sense of closure about relatives who perished in the Holocaust.

“People want finality. They want to know when their father died. This is important to people. I’m not talking just about genealogists who are doing nice charts.”

His main message seemed to be that an astonishing quantity of Holocaust records exists, and that much of it is become accessible as never before. ♦

© 2001

* * *

Holocaust Museum begins work on central index of names

The U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington D.C. has begun work on a central index of names using an astonishing and diverse range of Holocaust sources, including the so-called Auschwitz Death Books, copies of which the museum acquired only three months ago.

“We have about 500,000 names on the data base at the moment,” said Peter Lande, the retired career diplomat who is a leading consultant to the project. “It’s small, but it’s growing.”

Speaking at a meeting of the Jewish Genealogical Society of Canada during Holocaust Education Week, Mr. Lande gave a sense of the enormity of the project as he described some of the sources being used.

During the Shoah, the Germans confiscated Jewish records of all kinds from all over Europe and shipped them to Berlin. When the Russians overtook Berlin in 1945, they seized these records and stashed them into archives in Moscow. In recent years, personnel from the U.S. Holocaust Museum have been permitted to microfilm some of these records, Lande said.

Similarly, museum personnel have attained copies of many Nazi-kept lists of deportations, transports and concentration camp inmates, as well as a surprising amount of Holocaust-era Polish-Jewish records located in French archives. In 1944, all Jews in Nazi-occupied Hungary were required to provide detailed family trees to the authorities, and the museum expects to include these in the master index as well.

The Auschwitz Death Books, which the Russians confiscated from the Nazis and kept hidden in Moscow until 1990, provide many details about inmates. Similar books from Bergen-Belsen have also recently come to light. A list of 250,000 Jews from Lodz, a list of Jews in France prior to the Nazi invasion, even Schindler’s celebrated list of saved Jews will eventually be integrated into the central index, according to Mr. Lande, who said that more than two million names are waiting to be input.

“It’s never going to be nice and neat,” he said. “It’s going to be a cut-and-paste index. Think of a jigsaw puzzle with millions of pieces and no pattern. That’s what we’re working on.”

The museum’s central index will certainly be a boon to Holocaust researchers and genealogists, but Mr. Lande expressed indifference to the revisionist preoccupation with the number of Jews killed. “The death of six million people is a statistic, the death of one person is a tragedy,” he said. “That’s my approach.” To further elucidate his philosophy, Mr. Lande quoted the American writer William Faulkner: “The past is never dead; in fact, the past is never passed.”

Mr. Lande appealed for 10 volunteers in the Toronto area to enter names into a computer, and another 10 to act as proofreaders. “Our problem is not a lack of information,” he said. “We have lots of information, and we’re getting more every day…. What we need is people to enter the data and to proofread the data.”

Mr. Lande’s encyclopedic knowledge of the Holocaust became especially apparent in the question-and-answer session that followed his talk, when many people asked about many respective localities and concentration camps. “Treblinka? Forget it,” he said in answer to one questioner. “There was no work detail at Treblinka — off the train, and that was it. All we have are transport lists.”

To another, he explained that contrary to popular belief, being shipped to Auschwitz was not necessarily a death sentence. “If you were under 15, you went into the wrong line immediately, and the same if you were over 45,” he said. “If a person was between those ages, there was a fair chance that he was put into a work detail and shipped somewhere else.”

Comparing the Holocaust Museum’s envisioned index with the three million names already on record at the Yad Vashem museum in Israel, Mr. Lande explained that Yad Vashem’s records were based entirely on personal memory, whereas the Holocaust Museum’s records would come entirely from documentary sources. ♦

© 1998