A picture, according to proverb, is worth a thousand words, but sometimes the power of a photograph to illuminate a setting seems to go well beyond the descriptive abilities of language. Genealogists are often keen, therefore, to find good generic photographs, illustrations and other visual materials to enhance their family tree research.

A picture, according to proverb, is worth a thousand words, but sometimes the power of a photograph to illuminate a setting seems to go well beyond the descriptive abilities of language. Genealogists are often keen, therefore, to find good generic photographs, illustrations and other visual materials to enhance their family tree research.

As defined by popular usage, a postcard is a tiny piece of vacation ephemera, purchased impulsively at a news-stand in a foreign destination, then dropped into a mailbox with a few scribbled bon mots as a consolation to friends and loved ones at home.

Since the mushrooming interest in Jewish genealogy mushroomed of the last 25 years, postcards that depict Old Country scenes and places (synagogues, town-halls, market-squares, cemeteries) have become a much-valued and much-traded commodity.

In general, old postcards command increasingly respectable prices at antiquarian fairs and on the internet. Prices have risen accordingly for postcards that depict quaint shtetl scenes or romanticized views of Jewish life.

Gerard Silvain, a Parisian collector of Jewish postcards, has presented a tremendously evocative assortment of postcards in Yiddishland, a small thick hardcover book published by California-based Gingko Press in 1999. As highlighted in Yiddishland, Silvain’s presentation of Jewish postcards seems unsurpassed in quantity as well as quality.

“When, in 1964, for family reasons, I became interested in Judaic postcards, I was stupefied by the abundance and wealth of my discoveries,” he writes. “I was immediately swept into an exploration which was as exhausting as it was exalting.

“When, in 1964, for family reasons, I became interested in Judaic postcards, I was stupefied by the abundance and wealth of my discoveries,” he writes. “I was immediately swept into an exploration which was as exhausting as it was exalting.

“Tirelessly, magnifying glass in hand, I rummaged through the bookstalls on the banks of the Seine, dusty bookshops, the Parisian flea markets, suburban junk sales and specialist salons. The mineral I extracted from these mines which I systematically exploited vein by vein resulted in a collection of several tens of thousands of Jewish postcards.”

Yiddishland offers a rich cross-section of Silvain’s collection under such categories as Vilna and Lodz; the street; restaurants, shops, trades; schools, hospitals, hospices, cemeteries; synagogues; and culture and politics.

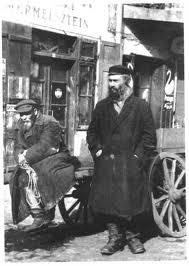

Its pages are brimming with redolent images: children playing in the street, a kerchiefed woman selling hot soup in the market, a bearded Jew leading his tethered cow, a knife-grinder at his wheel, a peddler selling prayer-shawls door to door; and barbers, beggars, cobblers, porters, rabbis, schnorrers, stall-tenders, tailors, water-carriers.

In some pictures the streets seem dirty and roughly cobble-stoned, the houses dilapidated, the people impoverished and sad. But in others the buildings and people reflect prosperity and rootedness. Thus the book adequately captures the diversity and contradictions of the shtetl.

To contact Gingko Press, phone 415-924-9615 or email gingko@linex.com.

Avotaynu Inc., the genealogical publisher, offers electronic images in JPG format of a growing assortment of Jewish postcards. Upon visiting Avotaynu’s web site at www. avotaynu.com, one may preview an image in low resolution, then download a high-resolution replica for US $2.50 (minimum order US $10).

* * *

Genealogists, travellers and representatives of Jewish institutions may find The Jewish Year Book 2001 of interest. Published in association with the Jewish Chronicle and edited by Stephen W. Massil, the 376-page volume is a thorough regional compendium on British institutional Jewry, including synagogues, charities and many communal organizations.

Published by Vallentine Mitchell, the Year Book also offers a contemporary Who’s Who of British Jewry, obituaries from the past year, and numerous essays on aspects of Anglo-Jewish history. A 60-page listing enumerates major Jewish organizations around the world by country, with capsule histories of the Jews for each country. The entry for Israel seems particularly strong. ♦

© 2001