From The Toronto Star Weekly, July 1913

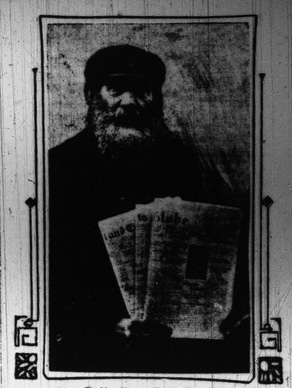

Zeth Slavin had to flee the Czar’s domains because his customers were massacred — Now he sells papers at corner of Yonge & Adelaide — Sorry he did not come sooner

By Gregory Clark

Zeth Slavin’s face is well known to most people whose work brings them to Yonge street. He sits, a sort of benign prophet, brooding over the materialism of all the world around him, at the corner of Adelaide and Yonge streets, now barking out mystic words (in reality the names of newspapers, if you have an ear that is deaf to the voice of romance), and now raising his eyes piously above the crowd.

Zeth Slavin’s face is well known to most people whose work brings them to Yonge street. He sits, a sort of benign prophet, brooding over the materialism of all the world around him, at the corner of Adelaide and Yonge streets, now barking out mystic words (in reality the names of newspapers, if you have an ear that is deaf to the voice of romance), and now raising his eyes piously above the crowd.

For a second, as you pass his corner, you get a glimpse of some spired and domed city of the East, with its holy men chanting sacred verses at the cross streets.

But Slavin is no Mussulmen, and his voice is not hushed in the name of Allah. He is a Russian Jew, and his message to the world is “Globe, Mail, Woild, Star, New Tel’gam.”

With the assistance of a tiny Jew newsboy in the role of interpreter, Slavin’s story was drawn out.

He living fifty-nine years in a Russian town which shall be as nameless here as it is unpronounceable. And for two years he has been in Toronto. His eyes gleam when he tells you of this country, where no one spurns you on the street, and where, even in the purchase of a newspaper, as fine a looking Gentile as you would see in Russia, accompanies the copper with a smile and a cheery grunt in salute. “Wonderful, wonderful,” says Slavin, with rolling eyes and outspread wagging palms.

Made Shoes in Russia

He made shoes in Russia. He shows you his hands, with their callouses and scars as evidence of this statement. But Gentiles would not come into his part of the little town, and his own people kept dribbling away to America.

“No money, no money!” interjected Slavin during the street arab’s translation of the exodus.

Slavin wished to stay in his narrow street, and not trust his fading hair to to the mercy of a new land. But he had to eat!

And now he wants to know why he did not come here fifty years ago. That is the explanation of his far-away glances, his ecstatic eye-rolling. Every time a smile is thrown in gratis with the cent, he returns it eagerly, then stares up to the clouds.

There is no fear of a score of sweaty cavalrymen riding down into his part of the city and swinging their sabres among the children and the old people. He leaves his house early in the morning, and knows he will find it safe at evening, except for the petty ravages of a health inspector.

The Massacre

When asked if he had ever seen a massacre of his people, Slavin would not speak for a long while, but the expression of his eyes told what he was seeing again. He doesn’t remember distinctly. All he knows is that the narrow street in which he lived sloped quite steeply, and that down it one day swept a laughing, swearing body of cavalrymen who swung their sabres, and jeered at each other every time a sabre fell on empty air. They passed at a gallop, and disappeared at the foot of the street. ♦