In 1937, the vice-principal of Central High School of Commerce came into our graduating accounting class as a visitor to announce that there was a job opening.

In 1937, the vice-principal of Central High School of Commerce came into our graduating accounting class as a visitor to announce that there was a job opening.

“There is no reason for any Jewish student to apply for this job because the employer doesn’t want a Jew,” he said.

That wouldn’t happen today, thankfully, because of anti-discrimination laws.

But it does illustrate the gulf that separates me, as a student in that class, from the present generation. I only know that my contemporaries and I had to fight hard for any success we achieved.

This is not to say that the present generation does not work hard, but it’s in a different atmosphere.

One of my fellow students was the late Lewis Moses who became a towering figure in the Zionist movement. Another was Howard Orfus who became a successful developer and had a street named after him.

One of my fellow students was the late Lewis Moses who became a towering figure in the Zionist movement. Another was Howard Orfus who became a successful developer and had a street named after him.

Others, including myself, had less spectacular careers, and, unfortunately, a lot of them are no longer with us. (My own career was in journalism, and after stints at the Ottawa Journal, and the Toronto Star, and as a professor at Sheridan College in Oakville, I ended up writing for the Canadian Jewish News on a part-time basis.)

It was a far different Jewish community then.

For recreation we went to the Jewish Boys Club on Simcoe Street, or when the family could afford it, to see a Jewish stage show at the Standard Theatre on Spadina Avenue.

In the 1930s we played tennis in the “gully” courts in Bellwoods Park with hand-strung racquets with wire. Bill Forman, Bernie Laytner, Maurice Cerezni and Murray Weinberg were among the players. Those courts are no more, and the “gully” has disappeared.

There was plenty of interest in young Zionist clubs (socialist, labour or what have you) and they met in dingy, second-floor rooms most of the time.

The big thrill was to save up a quarter to go to Shea’s vaudeville on Bay Street on the weekend to see a movie and a stage show featuring stars of the day such as Ben Bernie. It was in those days that you could go to the Duchess Theatre on Dundas Street near Bathurst for 10 cents (including a free popsicle) to see an afternoon show.

Just down the street, on Dundas, was a fruit store run by Ed Mirvish, now the Royal Alexandra Theatre entrepreneur and proprietor of Honest Ed’s whose garish lights twinkle at Bloor and Bathurst streets.

We arrived in Toronto in 1933 from Bowmanville, 50 miles away, where my late father, David, had a dry goods store. He often travelled in the country thereabouts trading goods for chickens and eggs which he sold in Toronto.

We arrived in Toronto in 1933 from Bowmanville, 50 miles away, where my late father, David, had a dry goods store. He often travelled in the country thereabouts trading goods for chickens and eggs which he sold in Toronto.

After we moved, I attended Charles G. Fraser public school on Manning Avenue.

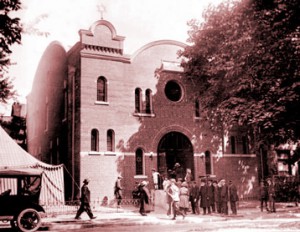

I had my bar mitzvah at the Shaw Street Shul, now part of Beth Emeth Bais Yehuda, a Conservative shul in Downsview.

It was at the old Shaw Street Shul that I said Kaddish for my father in 1935. He died in his bed at the age of 57 at 1103 Dundas Street West because there was no penicillin or other antibiotics at that time to combat pneumonia.

My mother had me go round in the middle of the night to rouse my second cousin, Yechiel Berman, on Givins Street to tell him the sad news.

My late mother (Rose was her first name) died in 1946 in Ottawa of cancer.

At that time, in the ’30s, it was known that the more affluent Jews attended Goel Tzedec or the McCaul Street Synagogue, or the Reform Holy Blossom Temple, while others went to smaller shuls, some of them in shtiebls or unfinished basements.

For some reason, the Men of England Synagogue on Spadina Avenue (it is no more) was the focus of a lot of attention.

My father’s Romanian cousins and friends persuaded him to attend the old Romanian shul downtown that eventually became Adath Israel Synagogue.

The bitter political battles between then Communist J.B. Salsberg and Conservative party standard-bearer Allan Grossman were legion, and those of us who were still politically innocent learned the hard way to lose our innocence.

There was no Jewish power or real electoral clout for Jews in the 1930s until war broke out, and most Jews were satisfied to try to make a living and stay out of harm’s way.

It is a real eye-opener today to see the Canadian Jewish Congress wade into policy issues and see the coverage that the battle for Jewish day school funds is getting in the media.

I doubt if there are any who want to go back to those “sha sha” days when Jews walked in fear of their shadows.

In those days, you could get a corned beef sandwich for 10 cents and a hot dog for five cents at any one of the delicatessens along College Street or Spadina Avenue. It is surprising how many of our people who served overseas yearned for those delicacies.

In those days, you could get a corned beef sandwich for 10 cents and a hot dog for five cents at any one of the delicatessens along College Street or Spadina Avenue. It is surprising how many of our people who served overseas yearned for those delicacies.

My first full-time job in 1938 was as a book-keeper and gofer at Belmont Cloak and Suit in the Fashion Building on Spadina Avenue. I was paid the munificent sum of $6 a week, which included long telephone harangues in the evening from one of the partners.

I shot up to $8 a week in my next job as book-keeper at Pearson Apple Company, which had unheated quarters in the old Esplanade market. But you were lucky to have a job in those days.

The proprietors, Archie Pearson and his father, were always fair with me.

But it was here that I had my first joust with the real world when a buyer for the firm absconded with cheques that I had prepared, instead of paying for tomatoes from Leamington growers which were to be sold at the Pearson stand.

During the mid and late ’30s, our family lived in rented homes on Bellwoods Avenue (now a Ukrainian church school) near Queen Street, on Dundas Street West, and on Roxton Road, near Dundas.

In those days, we rented out the second floor, or flat, which usually had a sink, to help pay the rent. We were not above scouring for coke (a residue left after the combustion of petrol) at Consumers Gas at $1 a bag, which was cheaper than the price of coal.

My late brother Maurice and my late sister Lillian were both working at low-paying jobs so it was with gleeful anticipation that I received a telegram from the Department of National Defence in September of 1939 asking me to report to Ottawa as a patriotic duty.

Canada had declared war on Germany a few days earlier.

I was to be paid $720 a year as a clerk-typist, but when I reported, it was to the Port of Ottawa — National Revenue. I wasn’t sent to National Defence, despite the patriotic come-on in the wire.

Eventually, I found my way back to Toronto as a reporter for the Toronto Star at the beginning of 1944, where I continued to work until 1965.

This gave me an opportunity to play tennis again, this time at the old Hudson Tennis Club on Dovercourt Road, just below College Street, where a public school is now located.

It was the only Jewish tennis club in the city and I was glad to play there, particularly since I had been blackballed when trying to join the club at Hanlan’s Point and at the Toronto Tennis Club on Price Street.

These are just some personal thoughts on a bygone era. ♦

This article first appeared in the Canadian Jewish News and appears here courtesy of the author’s family. © 2000 by the family of the late Ben Rose.