From the Canadian Jewish News, January 2014

Ninety years ago, New York newspaper editor Abraham Cahan was at the epicentre of international Jewish affairs — not a newsmaker himself but an opinion-maker, someone who had an extraordinary and powerful influence on the Jewish masses in New York, around the Diaspora and in pre-state Israel.

Ninety years ago, New York newspaper editor Abraham Cahan was at the epicentre of international Jewish affairs — not a newsmaker himself but an opinion-maker, someone who had an extraordinary and powerful influence on the Jewish masses in New York, around the Diaspora and in pre-state Israel.

As editor of the Daily Yiddish Forwerts (Forward) from 1902 to the postwar era, Cahan saw the Forwert’s circulation rise from a measly 6,000 to an astonishing 250,000 by about 1924. In the Teens and Twenties he traveled to Europe and Jewish Palestine and met with Jewish and world leaders, most of whom appreciated the awesome power he wielded with his Yiddish typewriter.

Born in Lithuania in 1860, Cahan did not learn English until after he arrived in America in his early twenties, yet he also managed to distinguish himself in the sphere of Jewish literature. Embracing the modern trend of realism, he crafted numerous stories about Jewish life in America for major magazines and attracted the attention of leading critics such as William Dean Howells, who became his champion. Cahan’s masterpiece, The Rise of David Levinsky, was published in 1917 and remains an outstanding example of American Jewish immigrant fiction.

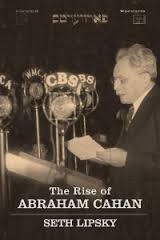

Seth Lipsky, a knowledgeable insider who founded the modern-day English-language version of the Forward, has written a well-researched and nicely balanced biography of his illustrious predecessor, The Rise of Abraham Cahan, which Nextbook Schocken Books of New York has published at 224 pages.

Seth Lipsky, a knowledgeable insider who founded the modern-day English-language version of the Forward, has written a well-researched and nicely balanced biography of his illustrious predecessor, The Rise of Abraham Cahan, which Nextbook Schocken Books of New York has published at 224 pages.

Since I am intrigued by the Jewish immigrant experience in America and by Cahan in particular, I was delighted to discover this book and especially that Lipsky was its author. My high expectations were not disappointed. Seemingly effortlessly, Lipsky re-creates the world of our immigrant ancestors of a century ago and brings to life their cares, concerns and political issues as Cahan himself would have perceived them.

Lipsky’s preface opens with this sentence: “A portrait of Abraham Cahan is the first thing that greets a visitor to the Forward in New York City.” Full disclosure: I have written many pieces for the Forward and once met Lipsky in the Forward’s office, under that very portrait if memory serves.

Cahan served an early stint at the Forwerts in the 1890s but left because, although a socialist and strongly pro-union, he wasn’t willing to tow the paper’s dry, ideological socialist line. He spent five years at a thriving New York paper, the Commercial Advertiser, serving under the famed muck-raking journalist-editor Lincoln Steffens. When Cahan requested assignments that would bring him “in close contact with life,” Steffens assigned him to the police headquarters on Mulberry Street, which immersed him in the street life of the Lower East Side.

Cahan was told to call in large breaking news stories from a pay phone. The first time he did so, he found a public telephone in a drugstore but needed help because he had never used a phone before. Cahan wrote many stories about Jewish life on the Lower East Side for the Commercial Advertiser, all necessary fodder for his fiction.

In 1902 the Forwerts lured him back as editor, granting him a free hand without interference because the paper was in danger of folding. Cahan’s first decree was that writers drop their pretentious high-falutin’ Yiddish for a more popular, street-level variety. He also broadened the paper’s scope beyond its narrow socialist worldview. “I have been in the outside world, I have discovered that we, the socialists, have no patent on honesty and knowledge,” he said. “The outside world is more tolerant of us than we are of it.”

Socialists, he added, needed to know something about the world beyond the Lower East Side. “It’s as important to teach people to carry a handkerchief in their pockets as it is to carry a union card. And it’s as important to respect the opinions of others as it is to have opinions of one’s own.”

His populist reforms were an instant hit and the paper’s circulation tripled to about 19,000 within four months. Shortly after the Kishinev pogrom of 1905, New York’s Jewish community reached one million, so there was still plenty of room for growth. Cahan’s objective was to help the masses of newly-arrived Jewish immigrants better acclimatize themselves to life in America.

When readers sent him letters detailing their personal problems, Cahan realized the letters were a “Godsend.” He established the Bintel Brief, a daily advice column that became immensely popular. The circulation continued to skyrocket.

In 1921 Cahan hired the great Yiddish writer Israel Joshua Singer as his Warsaw correspondent and later serialized his wildly popular novel The Brothers Ashkenazi. I. J. Singer joined the Forwert’s staff upon reaching America in 1934. A year later his lesser-known brother Isaac Bashevis Singer came to New York and also began working for the paper. Forty-three years later, in 1978, Isaac Bashevis won the Nobel Prize in Literature for stories that first appeared in the Forwerts.

Lipsky details Cahan’s battles with the playwright Jacob Gordin and the novelist Sholem Asch, also his meetings with Chaim Weizmann, David Ben-Gurion, Alfred Dreyfus, Vladimir Lenin, the Belzer Rebbe and other important figures. He also recounts Cahan’s politics: he was pro-German regarding the First World War until America entered the conflict. Not until the 1917 Russian Revolution did Cahan (and the Jewish world in general) throw its support overwhelmingly towards the Allies, Lipsky writes, mainly because a German victory would have threatened the socialist gains of the Russian Revolution as well as democracy in Europe.

Like many Jews, Cahan was initially lukewarm towards the Balfour Declaration of 1917, and only belatedly aligned himself more fully with the Zionists, apologizing for his earlier harsh criticisms. In the late Thirties, however, he was unflinchingly anti-Fascist and anti-Nazi, calling the Munich Agreement of 1938 a “shameful document” and describing Hitler as the “Fascist devil” who “made a fool of his terrified opponents, of the democratic countries, and of the whole civilized world.” His oft-stated wish late in life was to outlive Hitler and see his downfall — “I don’t care what happens to me after that,” he reportedly said.

When he died in August 1951, his funeral attracted some 10,000 people to the streets around the Forward Building on East Broadway; the service was broadcast on loudspeakers. Seth Lipsky has done a great service in rekindling the memory of this American Jewish colossus with such intelligence and discernment — and the sort of direct, inviting prose of which Cahan himself would have heartily approved. ♦