Rhea Clyman, an accomplished journalist born to a Jewish family in Toronto in 1904, wrote many front-page newspaper stories in the late 1920s and 1930s about political events and their tragic human consequences in Russia, Ukaine and Germany, but died in near-obscurity in New York in 1981.

Rhea Clyman, an accomplished journalist born to a Jewish family in Toronto in 1904, wrote many front-page newspaper stories in the late 1920s and 1930s about political events and their tragic human consequences in Russia, Ukaine and Germany, but died in near-obscurity in New York in 1981.

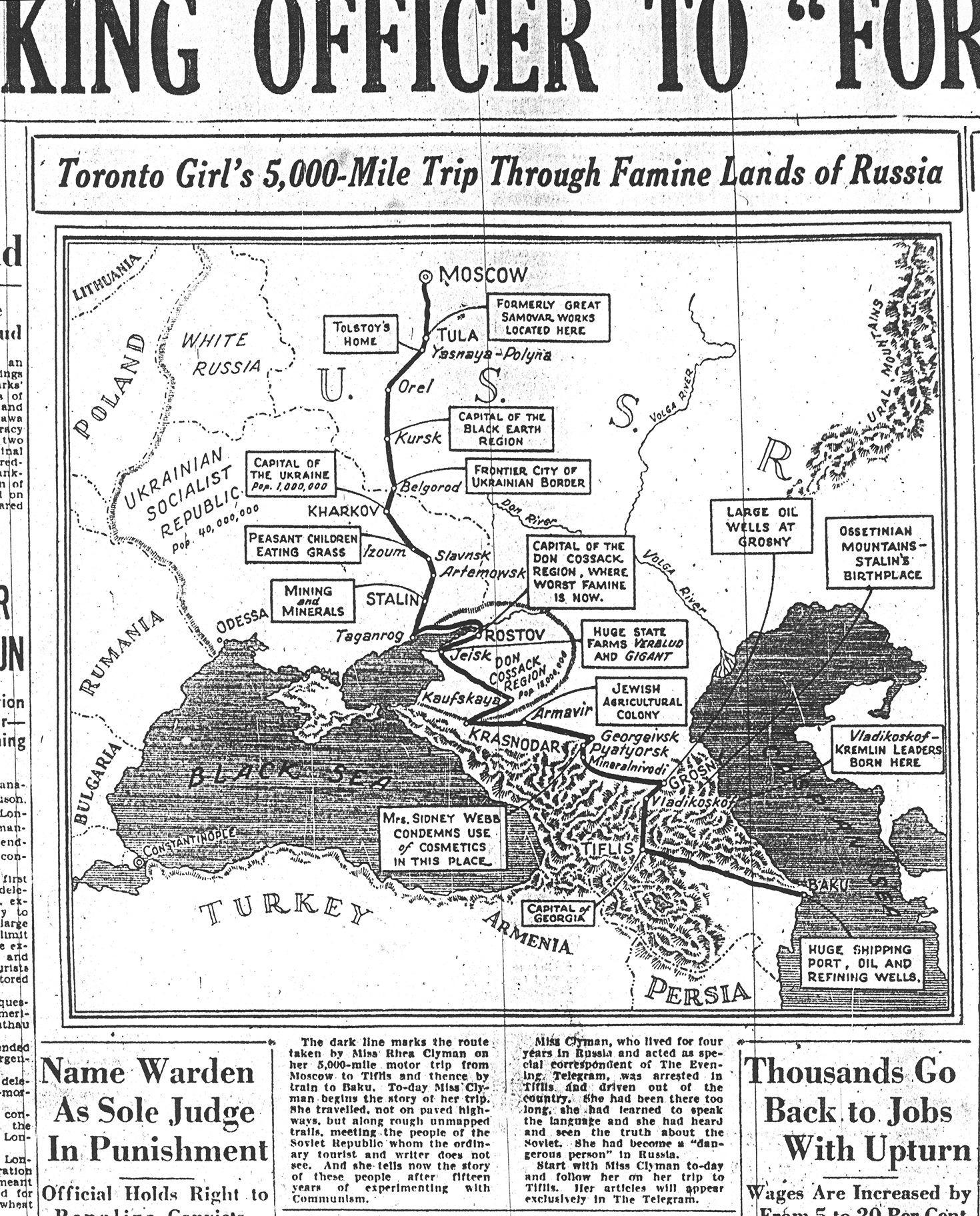

Clyman wrote rare and chilling eyewitness accounts of the Soviet Union’s government-induced famine in the Ukraine known as the Holodomor. She also traveled to Murmansk through treacherous terrain by automobile and train, and exposed the inhumane conditions of gulags and labour camps in Russia’s far north.

After becoming the first foreign correspondent expelled from Russia in more than a decade, she reported on events in Hitler’s Germany with equal fearlessness. Her stories appeared in the London Daily Express and the Toronto Telegram, where editors would often place them prominently on the first page and continue them inside.

Jars Balan, a scholar of Ukrainian studies at the University of Alberta, recently discovered Clyman’s stories and has been researching her life with the intention of writing a book about her. Balan recently presented a talk on the little-remembered newspaper reporter at a meeting of the Jewish Genealogical Society of Toronto.

A determined person, Clyman didn’t let the fact that she was a single woman hold her back, Balan said. Neither was she much deterred by the fact that she was missing part of a leg due to a streetcar accident in childhood.

Clyman studied business and commerce in Toronto, then went to New York and worked briefly as a secretary. She moved successively to London, Paris and Germany, acquiring an impressive smattering of French and German in turn. “She had a gift for picking up languages, and was very bright,” Balan said. “When she went to Moscow, she obviously learned Russian well enough that she didn’t need a translator.”

The timing of her arrival in Russia — late 1928 — “was auspicious,” Balan said. “The Soviet Union, under Stalin’s leadership, was just embarking on the first of its five-year plans to rapidly industrialize the Russian economy and forcibly collectivize Russian agriculture.”

Previously a supporter from afar of Soviet reforms, the 24-year-old Canadian wrote candid reports about the horrific plight of the prisoners she encountered in the remote northern forests and mines where they had been deported, and where they were fed just enough calories per day to keep them alive. “The Nazis actually learned about concentration camps from the Russians,” Balan said.

At Solovetsky Island Prison, an area that was closed to foreigners, Clyman typically bluffed her way through various perils. “She was incredibly resourceful and she was fearless,” Balan said. “The woman had moxie. She didn’t pull any punches.”

When she told her editor she was going to Ukraine, he bade her farewell and said he had already written her obituary. She and her companions drove through countless deserted Ukrainian farming villages where the villagers had already been deported. The few people remaining were so desperate for sustenance they were down on all fours, eating grass like cattle.

“In this area the famine didn’t even really taken hold until a few months later,” Balan said. “People were dying 25,000 a day just of starvation. We’re not including the people they shot or the ones who died in the gulag.”

Balan said he was interested in speaking with anyone in the audience who might have known Clyman or been related to her, and might help him resolve the various mysteries of her life. He seemed delighted when, towards the end of the evening, an elderly woman identified herself as Clyman’s first cousin. ♦