From the Canadian Jewish News, February 2014

As announced in obituaries in Variety, the Hollywood Reporter, the New York Times and other publications, screenwriting guru Syd Alvin Field died last November in Los Angeles at the age of 77.

As announced in obituaries in Variety, the Hollywood Reporter, the New York Times and other publications, screenwriting guru Syd Alvin Field died last November in Los Angeles at the age of 77.

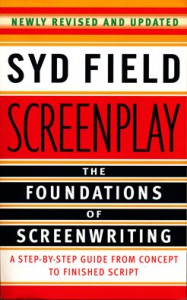

It’s been 35 years since Field’s book Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting was first published in 1979. It sold millions of copies, became known as the “bible” of screenwriting, and established him as a sought-after consultant who gave high-priced seminars to which hopeful novitiates and Hollywood insiders alike would flock.

After studying film at university, Field gained early seminal experience as a writer-producer and script-reader at a couple of Hollywood production companies. At one company he read more than 2,000 screenplays in little over two years, recommending only forty for further development. Only half of these — just one per cent of the total — did he consider worthy of production involving potential investment of millions of dollars.

In his book Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting, Field writes that the mountainous size of the slush pile of screenplays never varied “no matter how fast I read or how many scripts I skimmed, skipped, or tossed . . . .” He could synopsize two screenplays a day, but when he got to the third “the words, characters, and actions all seemed to congeal into some kind of amorphous goo of plotlines concerning the FBI and CIA, punctuated with bank heists, murders, and car chases, with a lot of wet kisses and naked flesh thrown in for local color.”

In his book Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting, Field writes that the mountainous size of the slush pile of screenplays never varied “no matter how fast I read or how many scripts I skimmed, skipped, or tossed . . . .” He could synopsize two screenplays a day, but when he got to the third “the words, characters, and actions all seemed to congeal into some kind of amorphous goo of plotlines concerning the FBI and CIA, punctuated with bank heists, murders, and car chases, with a lot of wet kisses and naked flesh thrown in for local color.”

This passage reminded me of my decades-long involvement as a freelance reader for a major Toronto-based commercial publisher. A huge pyramid of unsolicited action-adventure manuscripts towered behind my boss’s desk. Each time I visited he gave me a stack of them; I was paid $75 to $100 to read and write a two-page synopsis of each. Over time I learned to skim through the pages, seeking out what Field would call the essential “plot points” that help shape and define the narrative, dividing the ever-present sections that Field, like Aristotle, labelled Beginning, Middle and End.

Field gave immense thought to why he gave the thumbs-down to most scripts and what distinguished the precious few that won his approval. “What I was looking for, I soon realized, was a style that exploded off the page, exhibiting the kind of raw energy found in scripts like Chinatown, Taxi Driver, The Godfather and American Graffiti.”

But of course there was much more to it than that. Ultimately he looked beyond content to structure, finding the essential “plot points” that exist, or should exist, in all narrative films, no matter the story, setting, characters or genre.

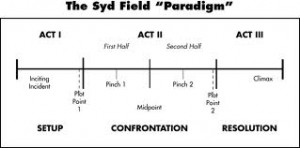

Most films run 90 to 120 minutes on average, Field reasoned, and a script should average about one page per minute of screentime. In a 120-page script, the beginning section, Act One, will be about 30 pages long. This is where the screenwriter sets up the story, establishes the characters, illustrates the situation surrounding the action, and launches the movie’s dramatic premise.

Act Two, approximately 60 pages long, is where the main character deals with the challenge earlier established, confronting a series of obstacles in pursuit of his or her dramatic goals. Act Three, filling the remaining 30 pages or so, delivers the resolution to the story. Field’s reductionist paradigm “Set-Up, Confrontation, Resolution,” along with the plot-points separating these sections, should be recognizable in all movies, he writes. When a set-up is weak, viewers lose interest, though they may not know why. When a film lacks a clear resolution, viewers will be disappointed, saying the plot went wrong or became confused.

Act Two, approximately 60 pages long, is where the main character deals with the challenge earlier established, confronting a series of obstacles in pursuit of his or her dramatic goals. Act Three, filling the remaining 30 pages or so, delivers the resolution to the story. Field’s reductionist paradigm “Set-Up, Confrontation, Resolution,” along with the plot-points separating these sections, should be recognizable in all movies, he writes. When a set-up is weak, viewers lose interest, though they may not know why. When a film lacks a clear resolution, viewers will be disappointed, saying the plot went wrong or became confused.

I must acknowledge that Field transformed the way I view films. Usually when I watch a film I try to identify two key plot-points — the “handshake” moment at the end of Act One when the dramatic challenge is defined, often with a handshake or vow, and the grand “reversal” at the end of Act Two that sets the stage for the resolution. Who dared say, before Field came along, that all movies were essentially the same in structure?

“Syd was the pioneer of the study of the screenwriting form,” screenwriter John Truby told the New York Times. “He was the first to challenge the old romantic notion that writing a good script was a gift of divine intervention and instead showed that it comes from a craft that can be learned.”

Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting is the best of Field’s handful of books on the subject. When I first read it many years ago I felt I had found the cinematic equivalent to The Anatomy of Criticism, Northrup Frye’s brilliant and unsurpassed classic of literary criticism.

Revised and updated numerous times, Screenplay stands up well to a second reading and its insights still seem exciting, but the movies cited as examples — such as The Godfather, Chinatown and Witness — seem dated and limited. Field is certainly not in the same league as Frye, but novice scriptwriters are nonetheless well advised to consider his cinematic paradigm as a sort of “great code” of the movies. ♦