From the Globe and Mail, November 1999

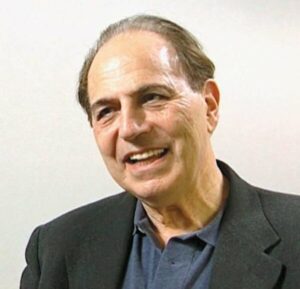

Rabbi Sherwin Wine of Birmingham Temple, Detroit, asserts that all of the patriarchs and prophets of ancient Israel are only myths — and so is the God of the Jewish people.

Rabbi Sherwin Wine of Birmingham Temple, Detroit, asserts that all of the patriarchs and prophets of ancient Israel are only myths — and so is the God of the Jewish people.

Heretical utterances for a rabbi? Certainly, in any previous age. But today Rabbi Wine is the founder of a secular humanistic arm of Judaism that has gained some 30,000 followers in about 35 congregations worldwide since he first articulated its principles in 1963.

Still actively spreading his gospel of faith in human reason as opposed to divinity, the 71-year-old new-age sage is scheduled to give a free public lecture next weekend in Toronto at the launch of Oraynu, a new secular humanistic congregation. The local group, whose name means “Our Light” in Hebrew, consists of about 50 Jewish families who acknowledge their Jewish roots but prefer to live their lives “independent of supernatural authority.”

Secular humanistic Judaism rests upon two pillars, according to Rabbi Wine. The first is an abiding appreciation of Jewish culture in all its myriad aspects from chicken soup to charity, latkes to literature. The second is “a personal philosophy of life which assumes that the fundamental power for solving human problems lies with human beings, not in some other place.”

Reached at his Detroit headquarters, Rabbi Wine says that secular humanism has touched a resonant chord within the Jewish world. “The reason our movement exists is because a large part of the Jewish people is unaffiliated and has not been appropriately served or recognized. Secular humanistic Judaism is an attempt to reach this community. We’re not assaulting the Orthodox, Conservative, Reform or Reconstructionist branches of Judaism. We’re hoping to serve people who can’t be served by these denominations.”

Even more than their counterparts in the highly liberal Reform and Reconstructionist movements, adherents of Jewish secular humanism have reshaped traditional Jewish ideas and practices to accommodate themselves as rationalistic non-believers in modern times. While they cling to cultural aspects of Judaism and may even spin dreidls and light menorahs at Hanukah, they’ve revised or rejected most of the religious tenets and rituals that mainstream Jews consider central to Judaism.

Even more than their counterparts in the highly liberal Reform and Reconstructionist movements, adherents of Jewish secular humanism have reshaped traditional Jewish ideas and practices to accommodate themselves as rationalistic non-believers in modern times. While they cling to cultural aspects of Judaism and may even spin dreidls and light menorahs at Hanukah, they’ve revised or rejected most of the religious tenets and rituals that mainstream Jews consider central to Judaism.

They don’t keep kosher but attempt to live by dietary laws that promote good health: they frown on the use of tobacco. Having removed any notion of miraculous or divine intervention from the stories of Hanukah, Passover and Purim, they commemorate these holidays in their own way. Fasting on Yom Kippur is a personal matter: Rabbi Wine doesn’t, but some do. Secular humanistic Judaism admits of no heavenly father, no heaven, no angels, no afterlife, no messiah, no mysticism whatsoever. “There’s only one world, the natural world,” the rabbi declares.

Each Saturday, in scores of locales in North America, Europe and Israel, congregants meet for “celebrations” (not “services”) in buildings that are usually known as centers (not synagogues). Whereas a traditional Sabbath service involves prayers and a reading from the Torah or Pentateuch, a secular humanist celebration generally opens with songs and a reading from any Jewish literary work considered of merit. They acknowledge that the Hebrew Bible contains important legends and ethical lessons, but do not regard it as being any more sacred or central to Judaism than, say, the latest works of Yehuda Amichai, a contemporary Israeli scribe. (“He’s an extraordinary poet,” asserts Rabbi Wine. “In our Sabbath celebration we have no reluctance to use his poetry, which is as great as anything to be found in the Bible.”)

Following the reading, the meeting continues with birthday, anniversary and other family-event announcements, a themed message (not a “sermon”) from the leader, a group discussion, and a period of conviviality with refreshments. Prayers are never part of the agenda. “In our celebrations, we reflect on the beauty of our world and affirm the powers that we possess to build a better world,” says Rabbi Wine. “The focus is on mobilizing our own energies as opposed to addressing a deity.”

Secular humanists dismiss the traditionalist notion that Judaism has survived throughout history because it doesn’t change with the times. “We would say that the real history of Judaism is that it has survived only because it has changed. The Judaism of the ancient world is not the Judaism of the modern world. Judaism adapts itself to new environments.

“It’s more accurate to view Judaism as a culture, because a culture can accommodate a wide variety of belief systems. Throughout Jewish history, a wide variety of belief systems have risen and fallen on the basis of whether they’re appropriate to their time. The reason Judaism has survived is because of its adaptibility.”

Jewish history, according to Rabbi Wine, has shown repeatedly that the Jews can rely on no one but themselves. “I believe this not because of some philosopher I’ve read, but because I feel Jewish history deeply in my bones. The message I’ve learned from that history is that we can’t rely on external justice. Not after the deaths of six million people.”

In its impulse to place Man above all, isn’t Wine’s self-styled brand of Judaism akin to the late Ayn Rand’s philosophy of objectivism? “Not at all,” he counters. “She didn’t have any celebration element or congregations — she had lectures, and she had an ethical system that we reject. She said the ultimate value is selfishness. We reject that. Our ethical values are built around service to other people and humanity.”

Predictably, many Jewish leaders are cool to the rise of a secularist fold within the Jewish flock. “I like to believe I have humanistic aspirations, but I’m a believer in a higher being we call God, so we’re separated in our activities,” says Rabbi W. Gunther Plaut, senior scholar of Toronto’s Holy Blossom Temple, a Reform synagogue. “We pray, they don’t pray. I’m quite sure they’re just as decent and just as moral as anybody else. It’s not my intent to judge them. I respect their right to interpret reality the way they see fit. But I’d rather that they would come around to a larger appreciation of the richness of our tradition.”

“The essence of Judaism is monotheism,” says Rabbi Reuven Tradburks of Kehillat Shaarei Torah, a Toronto Orthodox congregation. “An approach to Judaism without an approach to God is certainly going where Judaism hasn’t gone before…. You don’t necessarily change Judaism or give up what you believe in in order to attract people to Judaism. You don’t remake Judaism in the people’s image. You try to get the people to connect in whatever way they can.”

Still, the author of Judaism Beyond God and Staying Sane In A Crazy World predicts a bright future for the movement. He points out that it recently established an institute that has already ordained its first secular humanist rabbi, and that it has been admitted into the General Assembly of the United Jewish Communities of America, which met earlier this month in Atlanta. “That would not have been possible 30 years ago. Now it’s possible because we’ve established our credibility.”

Rabbi Wine’s lecture, Judaism Beyond God: Jewish Identity for Cultural Jews, is scheduled for Saturday Nov. 27, (1999) 8 p.m. at the Workmen’s Circle Building, 471 Lawrence Ave. W. Admission is free and all are welcome.

To celebrate its birth as a congregation, albeit one without a permanent home, Oraynu is presenting a series of lectures and discussions Nov. 26 & 27 at the Workmen’s Circle Building, and Nov. 28 at St. Andrew’s Junior High School, 131 Fenn Ave. For details, website www.oraynu.org. ♦