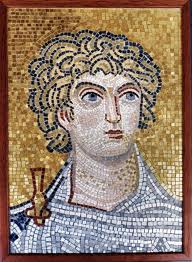

A Talmudic source indicates that after Alexander the Great conquered Palestine in 333 BCE, all Jewish boys of priestly families born the following year were named Alexander as a form of tribute.

Like his namesake, a contemporary Alexander is proving a skilled and savvy conqueror. Alexander Beider, the Paris-based onomastician, has marched from one province of Jewish names to the next in a bold campaign to illuminate their various etymologies. Having conquered the territory of surnames, he has now entered the field of given names.

His new book, A Dictionary of Ashkenazic Given Names: Including Their Origins, Structures, Pronunciations and Migrations, is being published this month by Avotaynu.

Beider’s two previous major works, A Dictionary of Jewish Surnames from the Russian Empire and A Dictionary of Jewish Surnames from the Kingdom of Poland, were ground-breaking studies that combined long theoretic introductions with exhaustive compilations of surnames.

Like its predecessors, the new book features a long theoretical introduction and a seemingly exhaustive compilation of about 15,000 Ashkenazic given names, all linked to a pool of about 735 root names. It traces many names back to the Talmudic period or the Crusades, documents known usages with dates, places, sources and notes, and maps out derivations and variations.

Regarding the root name Aleksander, for example, Beider notes that it has long been considered a “shem ha-qodesh” (holy name) despite its Greek origin. Its informal or “hypocoristic” form is Sander, and its vernacular forms include Ziskind and Zusman. Variations include Sanderman, Zenderlin, Zandrik and Shanke.

Like many great scholars, Beider achknowledges that he stands upon the shoulders of giants. They include Leopold Zunz, the 19th-century German-Jewish scholar, and Samuel ben Uri Shraga Phoebus, a 17th-century rabbi who compiled an early study of Jewish names.

Beider doesn’t get any better than when delicately untangling historic misperceptions that obscure the origins of certain names. Regarding Shneyer, for instance, he notes: “Due to a folk etymology misinterpretation, the Hebrew spelling of this name coincided with the combinations of the two Hebrew words ‘two’ and ‘light’, pronounced shney and or respectively.” Because of this association, some rabbis regarded the name as a shem ha-qodesh, suitable for use when calling someone up to the Torah.

Another erroneous folk etymology equated the name Fayvush with the Greek Phoibos and the Latin Phoebus, meaning ‘god of the sun.’ Consequently, Fayvush and its variants and derived forms were sometimes used as vernacular equivalents (kinnuim) for Samson, the Biblical name derived from the Hebrew noun meaning ‘little sun’.

The name Shrage, which derives from the Aramaic noun for candle, was often associated with Fayvush due to the erroneous connection of Fayvush with the sun. The true derivation of Fayvush is not Phoibos, however, but the Latin vivus, meaning ‘living, alive’. Fayvush was created as an equivalent form of the Hebrew name Chaim (‘life’) or Yechiel (similar derivation).

Some names seem to have multiple derivations and meanings. Nohkum or Nahum, for instance, is derived simultaneously from the Biblical prophet, from the Hebrew word meaning comfort, and as a shortform of Menahem. Likewise, Sholem derives from the Hebrew noun for peace, but because of its closeness to Solomon, both names are sometimes used interchangeably.

The very great penetration of Biblical names among Jews needs no explanation. I was unaware until reading Beider, however, that various now-common names such as Abraham, Adam, Isaiah and Israel only came into common use among Ashkenazim in the Middle Ages.

These are only a few of many questions explored in Beider’s latest magnum opus, which is a brilliant and monumental compilation. ♦

© 2001.