Today it has office towers, swank restaurants and hotels, the main bus terminal, city hall and the Eaton Centre but in 1911 it was where most of Toronto’s 18,000 Jews lived — in fact it was the one district in the city where Jews outnumbered any other people.

Today it has office towers, swank restaurants and hotels, the main bus terminal, city hall and the Eaton Centre but in 1911 it was where most of Toronto’s 18,000 Jews lived — in fact it was the one district in the city where Jews outnumbered any other people.

And as Stephen Speisman reminded a conference here, St. John’s Ward, the area between Queen and College and Yonge and University, became a shtetl for the large number of Jews from Eastern Europe who flocked to its crowded streets.

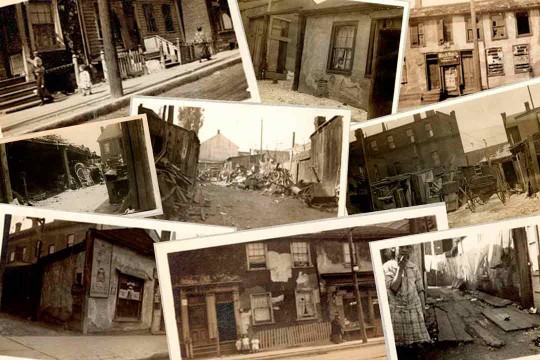

It had synagogues (four on Centre Avenue alone), mutual benefit societies, landsmanshaften, cheders, itinerant teachers, clothing factories (The Lowndes Co., Johnson Brothers, T. Eaton Co.) and houses so overcrowded and lacking in services that in 1911 Dr. Charles Hastings the medical officer of health reported that 108 houses in The Ward were unfit for habitation, yet most were occupied.

As Speisman, archivist for the Toronto Jewish Congress, told the conference here on Jews in North America, sponsored by the Multicultural History Society of Ontario and the Ethnic and Immigration Studies Program (U of T): “One structure housed three families in five rooms, one of which contained two sewing machines as well. Another cottage, rented for $20 a month, had four feet of water in its basement. Almost a third of the structures had no plumbing or drainage — waste was simply thrown into the yards.”

Terrible conditions

He said conditions in the rear cottages, those built in the laneways behind cottages fronting the streets, were the worst. Surrounded by stables, privies and yards full of garbage, the occupants found the odours so foul that they hesitated to open their windows, even in summer.

One Jewish businessman, Henry Greisman, a manufacturer of suspenders, built some decent houses, as an investment, not philanthropy, and rented them at a reasonable rate.

Not all the Jews worked in the clothing factories. They were prominent in “the salvage trades,” that is rag-pickers, bottle collectors, used furniture dealers or peddlers. By 1916 there were 600 Jewish rag-pickers in Toronto.

There were also Jewish barbers, shoemakers, grocers, restaurateurs, pawnbrokers, second-hand and dry goods dealers, but there were so many of these in the St. John’s shtetl that all could not make a living from them, and some family members had to take other work.

The end of the the Ward as the focus for Jewish life began as early as 1904 when a great fire destroyed many of the clothing factories. The T. Eaton Co. expanded, however, and took up the slack, but in 1912 a strike at Eaton’s led to many workers moving on to greener pastures, usually outside the old Ward.

In some cases families living in one room had to take in boarders to pay exorbitant rents. One three-storey structure on Teraulay Street had a factory on the top floor, while the outhouse adjacent to it was shared by 30 residents and the 40 employees of the factory. In the winter the privy was generally frozen.

After 1909, a Jewish day nursery and a free dispensary were established on Elizabeth Street south of Dundas. This was a direct attempt, Speisman said, to counter missionary activities, especially those of the Presbyterians, who provided such facilities to attract parents and children into the missions.

The nursery and dispensary were run by Dora Goldstick, a young Toronto midwife trained in Ohio, and Abe Hashmall, the first Jewish graduate in pharmacy at Uof T. The dispensary became Mount Sinai Hospital.

The Yiddish theatre, at first at the National in the former Lithuanian synagogue on University Avenue, and later at the Lyric which occupied a former Methodist church at Agnes and Teraulay (Dundas and Bay) provided formal entertainment. Their repertoires ranged from riotous and occasionally risqué comedy to Shakespeare and tragedies of heart-rending capacities.

Speisman observed: “The latter served a dual purpose; in the absence of a psychiatric service, the tragedy provided the struggling immigrant, especially the overburdened housewife, an inexpensive opportunity for catharsis. However much tzores one had, the character on the stage had infinitely more, and for a few pennies, one could go to the theatre and have a good cry.”

Jews began to spill out of the the Ward to Spadina Avenue and to the area which became Kensington Market, and further north and west. Today it is difficult to find evidence of that populous, vibrant Jewish shtetl in St. John’s Ward. ♦

This article first appeared in the Canadian Jewish News in 1983 and appears here courtesy of the family of the late Ben Rose. © 2012.