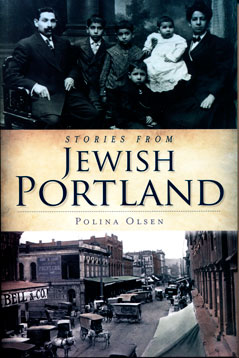

If you have roots in Jewish Portland, you may be interested in a recent book — Stories From Jewish Portland, by Polina Olsen (The History Press, Charleston, S.C., 2011).

If you have roots in Jewish Portland, you may be interested in a recent book — Stories From Jewish Portland, by Polina Olsen (The History Press, Charleston, S.C., 2011).

Olsen has collected many stories of the Jews of Portland. Their roots go back to the gold rush and their heart is the “old neighbourhood” of South Portland. The history dates back to the 1848 California gold rush, when Jewish merchants followed in the footsteps of the prospectors. Peddlers and would-be general store owners, they moved north as new deposits were found. Others arrived via the fabled Oregon Trail.

The author’s extensive research includes an examination of the archives of the Industrial Removal Office (IRO) where, admirably, she uncovered some forgotten history. The IRO was a private organization funded by the Baron de Hirsch Fund. From its headquarters on New York’s Lower East Side, it dispersed jobless Jewish immigrants to locations across the country where employment prospects were better. Between 1901 and 1922, the IRO sent 79,000 unemployed New Yorkers to 1,700 locations, including several hundred to Oregon.

Olsen writes:

“The IRO was established in response to the growing concerns of America’s established German Jewish population. In 1881, 80,000 Jews lived in New York. By 1901, the number had reached 510,000. New York Jewish charitable organizations were going bankrupt, and anti-immigrant legislation threatened. Some worried about an anti-Semitic backlash and even a radical socialist breeding ground in lower New York. The IRO hired lawyer David Bressler as general manager and sent agents around the country to elicit help from local B’nai Briths.

“IRO applicants fell into three categories. ‘Direct Removals’ just wanted to leave New York and accepted any destination. ‘Request Removals’ asked to locate near relatives or friends. ‘Reunion Removals’ joined family and friends previously sent out by the IRO. Frequently the husband came first, and his wife and children followed once he was established.

“As elsewhere, Portland’s IRO agents found work and housing for the newcomers. Led by Ben Selling, the Hebrew Benevolent Association worked with New York manager David Bressler. When Portland sent the IRO notices of job openings, the IRO responded with information about potential migrants. Letters from applicants and agents archived at the American Jewish Historical Society explain the process and provide a glimpse into this often forgotten organization.”

The second part of the book is filled with stories of the “neighborhood gang,” most accompanied with photographs. One typical story tells about the longtime director of the local Neighborhood House, who tirelessly aided newcomers for 32 years. “Ida Loewenberg (1872-1949) stands out among Portland’s early leaders,” it begins. “Born to privilege and schooled in Europe, her mansion and servants disappeared after her father’s death — but not her determination.”

The second part of the book is filled with stories of the “neighborhood gang,” most accompanied with photographs. One typical story tells about the longtime director of the local Neighborhood House, who tirelessly aided newcomers for 32 years. “Ida Loewenberg (1872-1949) stands out among Portland’s early leaders,” it begins. “Born to privilege and schooled in Europe, her mansion and servants disappeared after her father’s death — but not her determination.”

Aside from its appealing narrative, Stories from Jewish Portland is a well-designed and attractive book.

The Portland Tribune reported on June 16, 2011 that there were 47,500 Jews in the Portland area, far more than community officials had realized. However, most were not involved in congregations or other Jewish activities, the paper noted.

Rabbi Michael Cahana of Portland’s Congregation Beth Israel said he found that figure remarkable, adding: “The community had been operating for many years on the assumption that there was somewhere between 20,000 and 25,000 Jews.”

It is likely that many of Portland’s Jews, as well their cousins far and wide, will find parts of their family history told in Stories from Jewish Portland. ♦