They Were Used for Amusement by Dr. A. M. Rosebrugh, Who Secured Instruments from Dr. Bell, Inventor

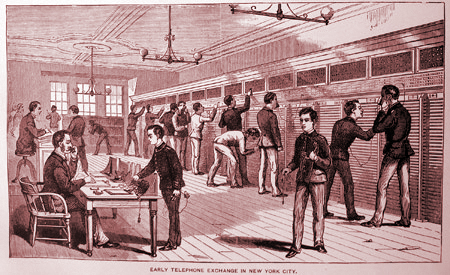

Wires Ran on Poles of Fire Alarm System

Dr. Rosebrugh Tested a Line to Hamilton and Started the First Telephone Company in Ontario

From the Toronto Star Weekly, September 9, 1922

By Knight N. Day

Toronto has had the closest connection with the evolution of the telephone.

Toronto has had the closest connection with the evolution of the telephone.

It was in 1876 that Edward Hanlan went to Philadelphia, after a boyhood afloat on Toronto bay and when he brought back the sculling championship from the Centennial Exposition. Citizens who went down there to cheer the “boy in blue” also saw at the exhibition another marvel — a Brantford, Ontario entry. These were some telephones entered by Alexander Graham Bell. The toy, which would let sounds be heard over a wire, interested a few, and induced Bell to keep at work, had made its bow.

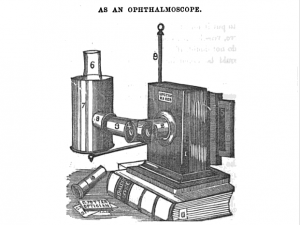

Before that time Dr. A. M. [Abner Mulholland] Rosebrugh [1835-1914], an eye and ear specialist, occupied a residence on Mutual Street, a few doors north of Dundas Street. He made the study of electricity a hobby. Also, as a toy for the amusement of his children, he had been experimenting, and discovered that by the use of a pair of a certain kind of tin-enclosed eardrums the human voice might be carried along cords or wires and be audible between rooms with closed doors. Rosebrughs were prominent members of the newly-built Metropolitan Church, had a wide acquaintance, entertained constantly. Parlour stunts in electricity were prsided over the amiable doctor, and he was invariably glad to have everyone join hands and get “shocked” by the battery he constructed himself. Batteries were not the common thing they are today, no one in town possessing them outside the colleges and schools, or among some of the doctors.

That was why those at the Rosebrugh parties would go home and tell their astonished parents “ghost stories” about conversation being carried on between some boys in the attic and some girls in the basement — “yes, and they event alked in whispers and could hear perfectly!”

Toronto’s first eye specialist had met Dr. Bell and corresponded with him, but before receiving six telephones which the Brantford inventor sent him in 1879, he had improved his made-in-Toronto toy so that wires were run between his new home further up on the east side of Mutual Street to the houses of several friends.

Early Phones Miraculous

One went easterly to the Rev. Dr. Withrow’s on Jarvis Street, another to Dr. Canniff’s on Church Street. Boys of these three homes went to school together, and the lines were utilized to facilitate study of home lessons. Holes were bored in the lower frame of the bottom sash, the wire passed thorugh, and connected with the oculist’s improved “ear-drum,” which now was encased in a wooden box with a small saucer-shaped centre through which one spoke and listened by turns.

One went easterly to the Rev. Dr. Withrow’s on Jarvis Street, another to Dr. Canniff’s on Church Street. Boys of these three homes went to school together, and the lines were utilized to facilitate study of home lessons. Holes were bored in the lower frame of the bottom sash, the wire passed thorugh, and connected with the oculist’s improved “ear-drum,” which now was encased in a wooden box with a small saucer-shaped centre through which one spoke and listened by turns.

“You may amuse yourself with these things I am sending you,” wrote Dr. Bell to the local inventor, who thus had gone so far along the same road in the leisurely pursuit of his hobby. For the balance of the year Dr. Rosebrugh experimented. Mr. Charles Potter, the city’s pioneer optician, was a close business friend of the doctor’s, naturally, so he determined to link him up by his latest improved device to facilitate his work as an oculist and to test its distance potentialities. He had again moved his residence to the southwest corner of Gerrard and Mutual Streets. Mr. Potter lived on Charles Street, the better part of a mile away.

The problem was how to string the wire. There were no telephone or electric light poles then, so ex-alderman Harry Piper was asked if he would permit the poles of his pet “fire and light committee” to be used for carrying wires.

“Mind you, at five minutes to nine every night we test the fire alarm bells,” Harry informed the doctor, “and of course nobody must use your talking affair at that hour, eh, Mac? See to that, Doc, ‘n it’ll be all right.”

Dr. Rosebrugh went home happy. He strung his wires. The line was a gratifying success. The doctor’s patients grew to wonder if he were not in league with certain party of evil repute. He would go to a box hanging upon the wall, speak into it, and apparently receive an answer to some enquiry of his regarding lenses. A story is told. A relative was invited to speak with Mr. Potter, who by signal had been got on the line.

“What shall I say?” was the hesitating remark.

“Suppose you say ‘Good morning,’” replied Dr. Rosebrugh.

“Good morning” — then, after a pause, “Well, it just says the same thing. I suppose it is some sort of an echo. Now what do I say?”

“Ask,” the doctor suggested, “ask Mr. Potter what he had for breakfast.”

“Ask,” the doctor suggested, “ask Mr. Potter what he had for breakfast.”

A deluge of ice water could not have made his relation bound from the box of mystery much quicker; he had experienced a thorough astonisher. “Why! Why! it says ‘bacon and eggs!’” Eventually someone used the line at nine o’clock and the concession was withdrawn.

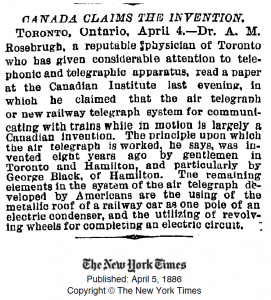

In 1883 Dr. Rosebrugh devised a scheme for duplexing metallic circuit telephone lines, which was adopted in time by the telephone companies. He started the first Canadian telephone company himself, after testing the long-distance capability of his latest improved apparatus by sending a confederate to Hamilton with a telephone to connect it with the telegraph wire. The local experimenters, which included Mayor Beatty and Mrs. Rosebrugh, met in Mr. Dwight’s telegraph office. The verses spoken by the lady were distinct enough at the Hamilton end to be heard across the room. Dr. Rosebrugh’s attempts at a patent ceased upon the announcement of Dr. Bell’s successful win in what had been a telephone perfecting race. ♦