Norman Bornstein, 90, remembers growing up at his grandfather’s Russian Turkish Steam Bath at 36 Centre Avenue in downtown Toronto.

Ten years ago (in 1993), he began documenting his memories of his mother’s father, Mendel Riman, but then put his papers away. Last February (2003), after 66 years of marriage, his wife Lillian died.

“I was very lonely, and I looked for things to do, and the opportunity came along for me to look at the draft of my grandfather’s story and to begin writing again,” he says.

Sara Edell Kelman brought Bornstein back to his writing. Kelman had begun writing the history of ber own family and discovered that her father, Pesach Edell, was a relative of Mendel Riman. While conducting her research, Kelman contacted Bornstein and last year agreed to work with him on writing his memoir.

“I was excited and fascinated by Norman’s story,” Kelman says. “I felt that it was a valuable piece of Toronto Jewish archival history.”

In his brief but nostalgic short story, titled Hot Rocks: The Story of the First Jewish Steam Bath in Toronto, Bornstein describes the central role Riman’s baths played in his life. (The baths were in operation roughly in the ‘teens and ‘twenties of the last century.)

Bornstein was born in an apartment above the shvitz (steam bath); his father died in a car accident when he was eight years old. He and his mother moved in with her parents on Brunswick Avenue and Bornstein began working at the steam baths as a teenager.

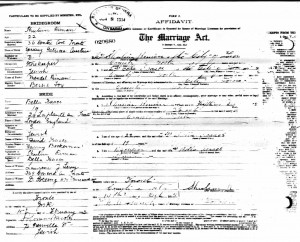

Born in 1865, Riman came to Toronto from Galicia in 1900.

“My grandfather was a smart man, and he opened the steam bath because he didn’t want to work on Shabbat,” Bornstein says.

At that time, there was a steady trickle of Jews arriving from eastern Europe.

“They needed to find work and lodgings. Helping organizations had not been formed yet, so it took individuals like my grandfather to fill the void,” Bornstein says, adding that his grandfather’s bath was probably the forerunner of the Jewish Immigrant Aid Society.

Hundreds of rag and bottle pedlars, bookmakers, swindlers, racketeers, rabbis, cantors and businessmen found their way to Riman’s baths, and Riman was always ready to help the new immigrants find their way in the new world, Bornstein says.

In Hot Rocks, Bornstein describes how the ovens for the baths were set up, how the steam was made and the bazems — bouquets of oak leaves — were prepared.

“More than likely, my grandfather used his own creative talent. He came up with what was to become the forerunner of the present day spas and health clubs.”

The history of Toronto in the early 1900s unfolds in Hot Rocks as Bornstein describes his family life, the growth of the city and the characters who came to the shvitz.

Bornstein, who went to Lansdowne Public School and Harbord Collegiate, began working at the baths when he was 14. He says the number of customers increased and included jockeys who came regularly to lose weight for a race the following day.

He describes Saturday nights as full of “fights, smokers, stags, floating crap and poker games.” Those days, he says, there was horseracing, basketball and hockey, “before Hockey Night in Canada. The bookies were busy with all the events.” He even describes a so-called “new sport,” cockroach races.

Even cold pop was available and, later, customers could order in a corned beef or pastrami sandwich for five cents.

As the Jewish community moved north, many of Riman’s customers, particularly those who didn’t have cars, began to drop away. One former customer built a new modern steam bath on Bathurst Street just south of College Street.

The business faltered with the stock market crash of 1929, the disintegration of the oven and many unforeseen costs. The family lost the business in 1933 when they were unable to pay the interest on a $4,000 mortgage. Riman died in 1945.

Bornstein, a retired broadcast producer and sales trainer, says that when he told people he was Riman’s grandson, “I was embraced and told how wonderful my zaide had been to them. This great man, my grandfather, who helped unknown numbers of immigrants, also took into his home his widowed daughter, my mother and her two little children raising us as his own sons.

“This was my zaide and I am very proud of him. He deserves a place in the story of the Jews of Toronto.”

Bornstein, who served in the Canadian Air Force during World War II, says, “I’ve had ups and downs in my life but I’ve enjoyed every minute. The downs have taught me to enjoy the ups even more.” ♦

This article first appeared in the Canadian Jewish News, and appears here courtesy of the author. © 2003 by Cynthia Gasner.