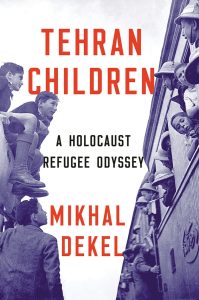

Book Review: Tehran Children: A Holocaust Refugee Odyssey, by Mikhal Dekel. Hardcover, 418 pages. Published by W.W. Norton & Company, 2019.

In September 1939, as Nazi militias approached their town of Ostrow Mazowiecka in northeastern Poland, the author’s paternal grandparents, like many others, were faced with a momentous decision: stay or flee eastwards into Russian-occupied eastern Poland, then the vast Soviet Union.

In September 1939, as Nazi militias approached their town of Ostrow Mazowiecka in northeastern Poland, the author’s paternal grandparents, like many others, were faced with a momentous decision: stay or flee eastwards into Russian-occupied eastern Poland, then the vast Soviet Union.

Both options were perilous. Some, knowing how miserable and grueling conditions were in Russia, ran to the forests to wait it out and see how events would unfold in Poland. Although he had no affinity for the communists, Dekel’s grandfather believed the odds for survival were better in Russia. Abandoning the brewery that had been in the family for generations, he and his wife and two kids packed two trucks with food, winter coats, jewelry and cash and headed to Bialystok and beyond.

“From the moment they left, they became migrants, tiny particles in the huge tide of refugees that swelled on Poland’s roads by foot, cart, wagon, car, and truck,” Dekel writes. For her father, Hanan Teitel, who was still a school-aged child, it was the beginning of a treacherous odyssey lasting 1,277 days and covering some 13,000 miles. As ugly as any modern-day refugee crisis, the sudden mass exodus from Poland involved — according to Polish sources — approximately 1.2 million Polish citizens with the number of Jewish refugees being as much as one-tenth of that figure.

The Soviets banished the Teitels to a slave-labor camp in the Arkhangelsk region of Siberia. Whereas the motto of German-run slave camps was “Work makes you free,” prisoners arriving at the Soviet gulag were greeted with the slogan, “Whoever will not work will not live.” Conditions were every bit as bad as those described by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn in Gulag Archipelago.

After being invaded by Germany in 1941, the Soviets declared a general amnesty for all former Polish citizens in the gulags. Suddenly released, the Teitels were forced to make an arduous trek over the Russian steppes to Samarkind in Uzbekistan. Refugees were packed into crowded “red cow” trains that, by Dekel’s description, seemed the equal of Nazi “cattle cars” for cruelty. Countless tens of thousands made the trip, and countless numbers succumbed along the way. Once in Samarkind, the problems of hunger, lice, deprivation and filthy conditions were exacerbated by diseases like typhus, malaria and tuberculosis; not even shipments from the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee could ameliorate the suffering.

Recognizing a chance to save their children, Zindel and Ruchela Teitel arranged to evacuate Hanan and his sister, Regina, to a Jewish orphanage in Tehran. But, like so many places in that terrible time, Tehran was half-starved and gripped with unrest. Fortunately, arrangements were made for a rescue mission to send more than a thousand Jewish “Tehran Children,” Hanan and Regina included, to British-mandate Palestine.

This is apparently the first time the gruesome story of the Tehren Children has been told in such depth. Dekel’s book is the story of two quests: her father’s, and her own as she retraces his footsteps, wanting to experience every locale of his story, even the gruelling train travel. The book includes colorful portraits of various interview subjects who help fill in parts of the story.

For those left with skeletal stories about relatives who died during wartime in Central Asia, this book will put a lot more substance on those bones. ♦