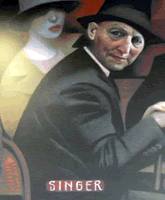

Seven years after the death of Isaac Bashevis Singer and 20 years after he won the Nobel Prize for literature, the literary world has produced three significant new books by and about the man who is one of the most important and popular Jewish writers of modern times. The last few months have seen the appearance of a new critical biography of Singer, a new memoir by one of his closest associates, and a novel, Shadows On The Hudson (Farrar Straus & Giroux), Singer’s fourth to be published posthumously.

Seven years after the death of Isaac Bashevis Singer and 20 years after he won the Nobel Prize for literature, the literary world has produced three significant new books by and about the man who is one of the most important and popular Jewish writers of modern times. The last few months have seen the appearance of a new critical biography of Singer, a new memoir by one of his closest associates, and a novel, Shadows On The Hudson (Farrar Straus & Giroux), Singer’s fourth to be published posthumously.

Originally serialized in the Jewish Daily Forward in 1957, Shadows On The Hudson was Singer’s first book about America — a country, he once famously proclaimed, that could never be the setting for a Yiddish novel. Written on the heels of his two masterworks, his 1950 novel The Family Moskat and his 1956 memoir In My Father’s Court, both of which are set in Polish-Jewish locales before the Holocaust, Shadows On The Hudson takes place in Manhattan and Miami Beach in the decade after the European cataclysm.

Perhaps not unexpectedly, the book “is long on shadows, short on the Hudson,” according to the English-language Forward. Since its main characters are drawn together primarily by their shared memories of prewar Warsaw, “New York City thus becomes a kind of palimpsest, which just barely conceals the sights, smells and sensibilities of another time and place,” reviewer David Roskies noted.

As Janet Hadda points out in her psycho-literary biography Isaac Bashevis Singer: A Life (Oxford University Press), the main problem “for the Eastern-European Jewish writer transplanted onto American soil was that he could not use his native language to describe his new life.”

Singer, of course, ultimately managed to overcome this difficulty by writing about transplanted Holocaust survivors and other Eastern European-Jewish exiles in such novels as Shadows On The Hudson, Enemies: A Love Story and Shosha. Many of his short stories set in America utilize a first-person narrator, a successful Yiddish writer in New York who receives a zany assortment of characters — just as Singer’s father, a rabbi, held “court” in the family’s humble apartment on Krochmalna Street in prewar Warsaw.

After the Shoah, Singer became a writer in turmoil, caught between “a dead past and an impossible future,” as Hadda puts it. In an article in the Yiddish journal Tsukunft, Singer compared his native Yiddish to an Old World grandmother transplanted to America, who cannot adapt to modernity and becomes confused and forgetful. “When she starts talking about the past (through the mouth of a true talent), pearls drop from her lips. She remembers what happened fifty years ago better and more clearly than what happened this morning.”

While millions of readers would agree that Singer produced pearls no matter what he was writing about, it is clear from Dvorah Telushkin’s Master of Dreams: A Memoir of Isaac Bashevis Singer (William Morrow & Co.) that he never lost his sense of displacement after leaving Warsaw for America in 1935.

However, at least part of Singer’s perpetual sense of dislocation as described by Telushkin must have come from advanced age. Telushkin approached him in 1975, offering him a weekly ride to Bard College in the Hudson Valley, where he was giving a course, in exchange for the privilege of auditing his lectures. She was only 21 at the time and he was already 71; she served as his personal assistant for the next 14 years, almost until his death in 1991 at the age of 87. (“You are the blessing of my old age,” he told her.)

Through a series of well-drawn and highly revealing vignettes, Telushkin paints a portrait of a man who was perpetually losing manuscripts, speeches, cheques, bank accounts — and himself, on the streets of the Manhattan through which he often walked great distances at his usual speedy clip. One room of his 86th St. apartment, which Telushkin calls the “chaos room,” was entirely given over to heaps of books, papers, old newspapers, letters and galleys of Yiddish manuscripts which often became impossibly entangled. He sometimes became frantic over the loss of an important cheque or speech, and would call Telushkin late at night in a panic.

Newspaper accounts about terrorism or riots sometimes filled Singer with fear. “I vill have to run. Vone day it vill come to it,” he would say. “Humanity vill no longer have the power to reverse all this. I vill have to run avay to a faravay island and tell no one vhere I go.”

On a few occasions Singer made large withdrawals from his bank accounts, just in case. “I am alvays jittery about the Jews,” he told Telushkin. “Vee can never really be sure. The truth is, I live in deadly fear of another Hitler. I must be able to have ready a little cash.”

Ultimately, Singer did flee — to Miami Beach, which supposedly was for him the equivalent of the “faravay island.” The comic irony was that the world avidly followed him into each of his hideaways, usually at his own invitation. After the Nobel Prize turned his life into a media circus in 1978, he would book hotel rooms in Manhattan under assumed names to escape the mad crush. Yet he would often give out his secret locations and phone numbers freely to people eager to see him. He seemed to thrive on chaos; he also knew that each person holds at least one important story, and he was always an avid listener.

Telushkin reports her observations about Singer’s meetings with celebrities such as Barbra Streisand, who visited him in 1982 in regard to her plan to write the screenplay for, direct and star in a musical film version of his short story, Yentl. Singer, who had sold the film rights to Yentl years earlier, thought the whole scheme egocentric and “meshige” and was disappointed to get nothing more than a kind note and a gift of chocolates, fruits and candies from Streisand. Singer later outlined his complaints regarding Streisand’s project in a famous self-interview that appeared in the New York Times.

Singer was less outspoken when he met Menachem Begin in New York at the latter’s request, shortly after winning the Nobel Prize. When he complained meekly to Israel’s then-prime minister that the Jewish state had resurrected Hebrew while allowing Yiddish to slide into mortal decline, Begin reacted forcefully, pounding a fist on the glass table for emphasis.

“With Yiddish,” Begin exclaimed, “we could have not created any navy; with Yiddish, we could have no army; with Yiddish, we could not defend ourselves with powerful jet planes; with Yiddish we would be nothing. We would be like animals!”

“Nu,” Singer shrugged. “Since I am a vegetarian, for me to be like an animal is not such a terrible thing.”

In marked contrast to the chaos that often seemed to swirl around him and which he often blamed on demons, Singer was completely punctilious about his work. He always completed his weekly quota for the Forward on time: he never missed a deadline nor took off sick. His dealings with New Yorker editors Rachel MacKenzie and Charles McGrath are well chronicled in Master of Dreams. Singer adored Mackenzie’s editing skills and her sensitivity to his work; yet that didn’t stop him from proclaiming on The Dick Cavett Show that he did all his own English-language editing.

Though at times his ego knew no bounds, he could also be exceedingly shy and humble. After MacKenzie became ill, the New Yorker assigned McGrath to work with Singer. The Nobel laureate would often take new manuscripts or corrected galleys to the New Yorker building in person, accompanied by Telushkin, then wait nervously in a coffee shop while Telushkin went up to the magazine’s offices. When after five years Telushkin finally admitted that Singer was sitting downstairs, McGrath “flew out of his office” and hurried down to meet him. “As we entered the coffee shop, Isaac jumped up with enthusiasm. He and Charles rushed toward one another and shook hands vigorously.”

Through many such vignettes, Telushkin paints a loving, vivid and fascinating portrait, capturing Singer’s many engaging qualities, his impish humor and wit, his catalog of eccentricities and, sadly, the paranoia and helplessness that seemed to overtake him in his last few years when he became so mistrusting and ambivalent towards her that he called her “the curse of my old age.”

Serious readers owe Telushkin a debt of gratitude for paying such particular attention to Singer’s pure-minded philosophy of literature. Singer believed that a writer was “an entertainer in the highest sense of the word” who had no business preaching or delivering timely social messages; and whose mission consisted entirely in telling a good story. (Once asked if he had a message for the leaders of the world, he replied: “I vould tell them you don’t need my message — there are Ten Commandments somevhere. You read them and if you can keep them, then you don’t need my message. And I vill continue to write stories vithout messages forever.”)

While I thoroughly enjoyed the directness and depth of Master of Dreams, regretting only that Telushkin hadn’t met Singer a few decades earlier, I had some qualms with the Hadda biography. Hadda, an American psychoanalyst and Yiddishist, applies a psychoanalytic magnifying glass to Singer’s life, examining and assessing such problematic areas as the sexual relationship of the author’s parents. Although the book presents many useful insights and biographical information, its analytical tone is unnerving at times, and one senses that Singer would have abhorred this somewhat clinical treatment of his life. ♦

© 2002