When Abraham de Sola arrived in Montreal in 1846 to serve as spiritual leader of the city’s Spanish and Portuguese Congregation, he carried a letter from his father, David de Sola, rabbi of London’s Bevis Marks synagogue, beseeching the community to look after him because he was only 19 years old.

rabbi of London’s Bevis Marks synagogue, beseeching the community to look after him because he was only 19 years old.

Abraham de Sola was probably Canada’s first rabbi and was clearly destined for greatness. Word soon spread of his powers of oration and his lectures before various learned societies in Montreal typically drew overflow crowds. McGill University made him a professor of Hebrew and rabbinical literature and gave him an honourary degree, probably the first ever awarded to a Jew in an English-speaking country.

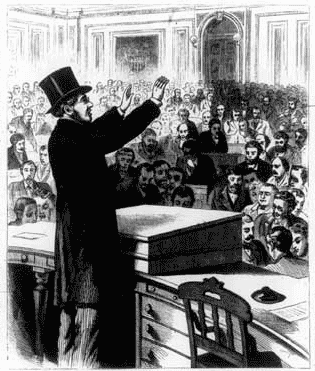

He gave pulpit lectures frequently in the United States and in 1872, by invitation of President Grant, he opened the US Congress with prayer. Because the event helped to warm relations between the two countries after a notable chill, British Prime Minister William Gladstone sent him a personal note of thanks, knowing that despite his years in Quebec, the London-born rabbi was still a British subject.

Among his many accomplishments, Abraham de Sola influenced Canadian medical history through a series of articles in which he endorsed the use of pain-killing medication in childbirth. Quoting Hebrew sources, he asserted that administering anesthesia was not contrary to scripture (Genesis 3:16), as some had contended, because it lessened the pain but not the toil or labour of parturition.

“In the history of Canadian Jewry, it is doubtful whether there could be found another religious leader who had the same impact as Abraham de Sola,” writes Rabbi Wilfred Shuchat in The Gate of Heaven, his masterful history of Montreal’s Shaar HaShomayim congregation.

A shining beacon in Canada’s 19th-century Jewish community, Abraham de Sola was descended from an illustrious Sephardic family that had been well known in Toledo and Navarre a full millennium earlier. The de Solas drew their name from an estate in northern Spain and were also eminent in Cordova, Seville, Tudela, Castile and Aragon. The persecutions of the 14th century forced them to Granada, and the expulsion of 1492 forced them to flee to Portugal, Holland, the Caribbean and other countries.

In Lisbon, David de Sola (Abraham’s third-great grandfather) was tortured under the Inquisition and two of his sons were burnt at an auto da fe. Aaron de Sola (Abraham’s second-great-grandfather) escaped from Portugal on a British ship and arrived in London in 1749, where “he and his family at once openly proclaimed their fidelity to Judaism,” the Jewish Encyclopedia records.

Aaron relocated to Holland and various of his sons established family dynasties and businesses in Amsterdam, Curacao and the United States. Son Benjamin served as court physician to William V. of Orange and son Isaac served as a general in Bolivar’s army during the Venezuelan war of independence.

Abraham’s father David de Sola, who fulfilled a historic role at Bevis Marks, married the daughter of British Chief Rabbi Meldola, scion of another distinguished Sephardic family from whom many illustrious physicians and rabbis descended.

As if to further enhance the family name and legend, Abraham de Sola himself married a daughter of Henry Joseph of Berthier, nephew of Canadian-Jewish pioneer Aaron Hart. His sons included Meldola de Sola, Canada’s first native-born rabbi, who led the congregation after his father’s demise; and Clarence de Sola, a Zionist pioneer, diplomat and contractor who constructed railway and highway bridges. No doubt several new generations of de Solas are continuing to do their ancestors proud. ♦

© 2005