From the Canadian Jewish News, 1995

◊ Note: This article is being republished this week as a reminder of the eternal evil nature of “Amalek,” as represented during the days of WW2 by the Nazis, and in today’s world by the Hamas terrorist group.

It was, finally, the melody of a Hebrew song that brought Sora Vigorito fully back into the Jewish fold.

As a child, she had been tortured at Auschwitz. The Nazis had murdered all her loved ones except her father. She had met him for the first time after the war. Then death had pulled him away from her, too.

As an adolescent, she was befriended by a nun in an American orphanage who slowly gained her trust. “I poured out my anger to her,” Vigorito recently told a Toronto audience. “How could God take away my mother, my sisters, my family, and now my father? Why? What had I done in my young life for God to punish me? What kind of God was He?”

The nun explained that the Jews were meant to suffer because they had forsaken the Christian messiah.

Vigorito had recurrent nightmares. What she had encountered at Auschwitz had left her feeling dirty, impure, unworthy. Seeking redemption, she joined a Christian prayer group, married a non-practising Catholic, and earned a master’s degree in comparative religion. She observed both Christian and Jewish holidays. Although her husband tolerated her spiritual eccentricities, she was fired from her job teaching comparative religion at a Catholic girl’s school for delving too deeply into Judaism.

Her church-going also ended abruptly, after she complained privately to the priest following a service in which the Jews were vilified for killing Christ. “He chased me out of the church, shouting, ‘You damn Jew, get out, get out!’ I went out and I never came back.”

“My husband comforted me by saying, ‘See, I told you that all religion is hypocritical.'”

It was during a synagogue service that Vigorito heard that long-forgotten melody again, the first time since Auschwitz. It was being sung by the congregants, but she was too horrified to attempt to sing along. She felt goose bumps, chills, tremors, nausea. “Suddenly, I was reliving some of the most horrible moments of my life.

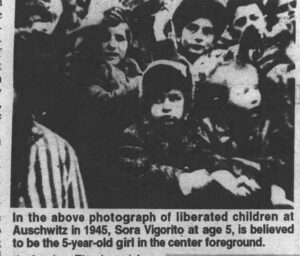

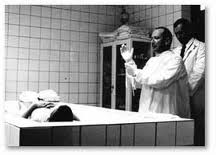

“You see,” she told a large spellbound audience at the Chabad Lubavitch Community Centre in Thornhill, “long ago, when I was three and a half, my sister Hanna and I were housed in the second story of Auschwitz-Birkenau, where Dr. Mengele had his laboratory. My sister and I were his lab animals.”

As one of 89 pairs of identical twins upon whom Dr. Mengele was experimenting, the sisters received spinal injections, which gave Hanna convulsions. Dr. Mengele took blood samples, injected tuberculosis into Sora, scraped away at bone, and performed other operations, all without anesthetics.

As one of 89 pairs of identical twins upon whom Dr. Mengele was experimenting, the sisters received spinal injections, which gave Hanna convulsions. Dr. Mengele took blood samples, injected tuberculosis into Sora, scraped away at bone, and performed other operations, all without anesthetics.

Vigorito recalls seeing piles of human beings through a hole in the wall: grotesque faces, eyes hollowed out and gray. “I didn’t understand the meaning of death, only that it was something horrible.”

“At night time, we’d be back in the crematorium, and no matter what Dr. Mengele had done to us, we’d always hear this melody outside, as though it was sung by 200 or 300 people.

“We heard it every night and I didn’t know what it was. But now I know that it was the traditional melody of Ani Ma’amin.

“We heard the melody and then we’d hear the screaming. And then the screaming would die down and it would be silent. And then we’d hear this metallic cranking. We heard it all the time.”

The day after Vigorito heard the melody again, a friend told her that the Hebrew lyrics were from Maimonides’s thirteenth principle of faith. They were a proclamation of undying faith in God — “even if He shall delay.”

“When she told me these words, I was beside myself. Every night I heard those people who could no longer deny their fate; the smell of their fate was in the air, there was no possibility to escape the fate before them. They were proclaiming their belief in God. And I thought: I want a faith like that. I don’t know how to get it but I want that.”

Two weeks before liberation, Vigorito’s sister went into a convulsion and died in her arms. When Dr. Mengele came the next morning to remove the body, “I hit him in the face with my little hands. He said, ‘This is what happens to children who hit the doctor,’ and he smashed my hand (with a hammer) on a marble plate. Then he put me back in my cage and that was that.”

Two weeks before liberation, Vigorito’s sister went into a convulsion and died in her arms. When Dr. Mengele came the next morning to remove the body, “I hit him in the face with my little hands. He said, ‘This is what happens to children who hit the doctor,’ and he smashed my hand (with a hammer) on a marble plate. Then he put me back in my cage and that was that.”

If the Russians hadn’t appeared at the gates of Auschwitz, Dr. Mengele would have killed her and compared her internal organs to those of her sister, says Vigorito, who declares herself to be the last of Mengele’s twins still alive.

Hearing Ani Ma’amin sparked Vigorito’s full return to Orthodox Judaism, a journey complicated by the fact that her husband, the father of her three children, was a Gentile with seemingly little affinity for Judaism. A rabbi eventually advised her to seek advice from the Lubavitcher Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson in Brooklyn.

“I told the Rebbe (Schneerson) that I was a Mengele twin, the only one alive, a Ba’al Tshuva, that I had koshered my home. . . . I said, ‘Here I am before you, and my husband is not Jewish. I’m ready to do what the Torah says I must do, but I need strength. Can you give me strength, Rebbe?’

“He looked up at me and I can’t describe the look in his eyes. The Rebbe said, ‘Don’t divorce your husband. Separate yourself from him, don’t have any physical contact with him, sleep in another room and everything will be fine.'”

Vigorito followed that advice, prompting her husband to ask: “What do you mean, Everything will be all right? What do you think I am?” But he acquiesced.

For several months, he was mysteriously absent at regular intervals. One day, he took her to a surprise meeting with the rabbi. Vigorito feared that he had arranged a divorce. To her amazement, the rabbi told her that her husband had been studying Judaism and wished to convert. Several months later, she and her husband were married halakhically (according to Jewish law) beneath a chupah.

Vitorito, a Cleveland resident, won an Emmy award several years ago for a documentary film that she made about her wartime experiences. ♦

© 1995