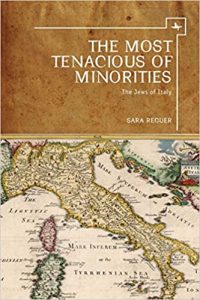

Review: The Most Tenacious of Minorities: The Jews of Italy, by Sara Reguer. Hardcover, 190 pages. Boston: published by Academic Studies Press, 2013. www. academicstudiespress.com

The Jews have been booted out of so many places during their history, it seems only natural that they should have a long and colourful past in the Italian “boot.” The first Jews arrived in Italy during the Etruscan period between the 10th and 4th centuries BCE and were of two types: wealthy international traders seeking new outposts and lower-class craftsmen seeking better living conditions for their families.

The Jews have been booted out of so many places during their history, it seems only natural that they should have a long and colourful past in the Italian “boot.” The first Jews arrived in Italy during the Etruscan period between the 10th and 4th centuries BCE and were of two types: wealthy international traders seeking new outposts and lower-class craftsmen seeking better living conditions for their families.

The rise of the Roman Empire was a two-faced coin for the Jews, bringing first good fortune but then national tragedy. As detailed in the ancient Jewish Book of the Maccabees, the Jews enlisted the Romans as allies in their fight against the Seleucid Greeks. But their erstwhile friends became their bitter enemies, conquered the Jewish state and destroyed the Second Temple in 70 CE.

The most famous (or infamous) vignette in Roman-Jewish relations occurred when the Romans shipped “thousands of Jewish war prisoners to Rome, where they were paraded in traditional Roman style down the main paved roads in front of throngs of Roman celebrators,” Reguer writes in this thorough history. “This was later commemorated in the Arch of Titus with its magnificent details of this parade, including the depiction of the Menorah taken from the Temple. The only ones not celebrating were Rome’s Jews, who quickly got to work raising money to redeem their co-religionists from slavery by ‘buying’ them.”

Long before the fall of the Second Temple and the Jewish dispersion, the Jews were a well-established minority in Italy, Reguer observes, and in Rome were sufficiently well-regarded by their fellow countrymen as to be accepted as “Roman citizens as well as neighbours.” Rome was then a city of perhaps 300,000, including roughly 12,000 to 40,000 Jews, many of whom had previously arrived from Alexandria and Israel. The extreme antiquity and durability of the Jewish community of Italy is why Reguer describes it as “the most tenacious minority in Europe.”

In a chapter on “The Medieval South,” the history attains a solid footing by drawing upon more readily available historical artifacts and documents; a legal letter colourfully describes a synagogue compound as “a main building, with rooms or small buildings nearby used as inns, hospitals, and gardens.”

Throughout each subsequent turn of history — the rise and fall of the Holy Roman Empire, Byzantium or the Eastern Roman Empire, and the Islamic caliphates of the Umayyads, Abbasids, Aghlabids, Fatimids, etcetera — the status and condition of the Jewish community is appraised. The Arabs who invaded Sicily accorded the Jews a protected but second-class “dhimmi” status, much as is still done in Arab lands today. The Crusades did not bring much displacement to Italy, but rather seem to have brought enormous trade opportunities and the potential of enormous profits.

Throughout each subsequent turn of history — the rise and fall of the Holy Roman Empire, Byzantium or the Eastern Roman Empire, and the Islamic caliphates of the Umayyads, Abbasids, Aghlabids, Fatimids, etcetera — the status and condition of the Jewish community is appraised. The Arabs who invaded Sicily accorded the Jews a protected but second-class “dhimmi” status, much as is still done in Arab lands today. The Crusades did not bring much displacement to Italy, but rather seem to have brought enormous trade opportunities and the potential of enormous profits.

The 12th-century Sephardic traveller Benjamin of Tudela recorded the presence of about 200 Jewish families in Rome, and described Jewish life in the north as well as southern cities of Naples, Trani, Apulia, Taranto, Otranto, Brindisi and Sicily.

The expulsions from Spain and Portugal infused the Italian Jews with a wave of Sephardim and Conversos, labeled “Ponentini” by the Italians — “those Jews who had either chosen or been forced into Christianity and were living as secret Jews in the Iberian Peninsula.” Once in Italy, many openly returned to Judaism, especially in the city of Ferrara. This era saw the rise of the first Jewish Ghetto in Venice, named after the iron foundry where the first walled-in Jewish enclosure was built in 1516.

The book also deals with the phenomenon of the Ghetto, how the Jews were treated during the Spanish Inquisition, the Italian Renaissance, and the German Reformation, and the quality of Jewish relations with Papal authorities down the centuries. Chapters titled “The Winds of Change,” “World War II,” and “Contemporary Italy” bring the history into the modern era. Sidebars throughout focus on many historically significant persons such as the Roman-Jewish historian Josephus; the poet Immanuel of Rome whose poem Yigdal, based on Maimonides’s thirteen principles of faith, has been included in the modern Jewish prayer-book; and Gershom Soncino who printed many important Hebrew works on the newly-invented printing press in the late 15th and 16th centuries.

“The story of Jews in Italy is one of re-creation and tenacious resistance to merging with the larger community,” Reguer writes in her Conclusion. “It is a story of economic creativity and of people locating niches for themselves when there were adverse laws limiting how they could earn a living, and it is the story of expansion when they were treated well.” It was also, she continues, a “story of intellectual creativity in the realm of Jewish thought, literature, and poetry, and in the larger world of the Italians,” and a story in which “the glue of the community” continued to hold together.

The Most Tenacious of Minorities: The Jews of Italy was written for the historian, not the genealogist, but it will undoubtedly give the latter an excellent, if somewhat academic, background to the subject; one drawback for the avid researcher, however, is that the book lacks a bibliography. Reguer, who became interested in the topic after marrying an Italian Jew, is chair of the Department of Judaic Studies at Brooklyn College, City University of New York. ♦

* * *

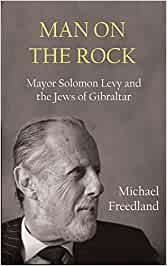

Man On The Rock: Mayor Solomon Levy and the Jews of Gibraltar, by Michael Freedland. Hardcover, 194 pages. Published 2013 by Vallentine Mitchell, London and Portland, Oregon. www.vmbooks.com

Man On The Rock: Mayor Solomon Levy and the Jews of Gibraltar, by Michael Freedland. Hardcover, 194 pages. Published 2013 by Vallentine Mitchell, London and Portland, Oregon. www.vmbooks.com

This book presents a colorfully written profile of Solomon Levy, the first “civil” (and still present) mayor of the tiny British territory of Gibraltar, located in the Mediterranean at the tip of the Iberian Peninsula, almost touching the African continent.

“He is not just the most devoted and patriotic Gibraltarian one could imagine, but a leader of the Rock’s Jewish community — only, according to some more optimistic assessments, about 800 people strong,” Freedland writes. “But since there are only 30,000 people altogether living there, it is perhaps, per capita, the biggest Jewish congregation in the world outside of Israel, close to 3 per cent (American Jews represent about 1 per cent of their nation).”

Levy’s family is descended from a long line of rabbis and he is at the center of events in Gibraltar as well as happenings within its Jewish community. A British journalist, Freedland has also written biographies of Leonard Bernstein, Fred Astaire, Andre Previn, Danny Kaye, Al Jolson and other figures. ♦

* * *

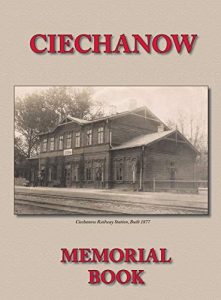

Memorial (Yizkor) Book for The Jewish Community of Ciechanow. Hardcover, 490 pages. Published 2013 by JewishGen, New York.

Memorial (Yizkor) Book for The Jewish Community of Ciechanow. Hardcover, 490 pages. Published 2013 by JewishGen, New York.

Half a century after it was originally published in Hebrew and Yiddish, the Memorial (Yizkor) Book for The Jewish Community of Ciechanow has just been republished in English translation in an attractive hardcover volume by JewishGen of New York. The book will appeal chiefly to historians and genealogists. Torontonians Miriam Dashkin Beckerman and Stan Zeidenberg were the translator and project coordinator respectively. ♦