Scottish novelist Walter Scott’s portraits of the Jew Isaac of York and his daughter Rebecca in his classic medieval romance Ivanhoe (1819) provides English literature with its strongest positive counterbalance to the stereotypical conception of the Jew as a dark misanthropic being along the lines of Shakespeare’s Shylock.

Scottish novelist Walter Scott’s portraits of the Jew Isaac of York and his daughter Rebecca in his classic medieval romance Ivanhoe (1819) provides English literature with its strongest positive counterbalance to the stereotypical conception of the Jew as a dark misanthropic being along the lines of Shakespeare’s Shylock.

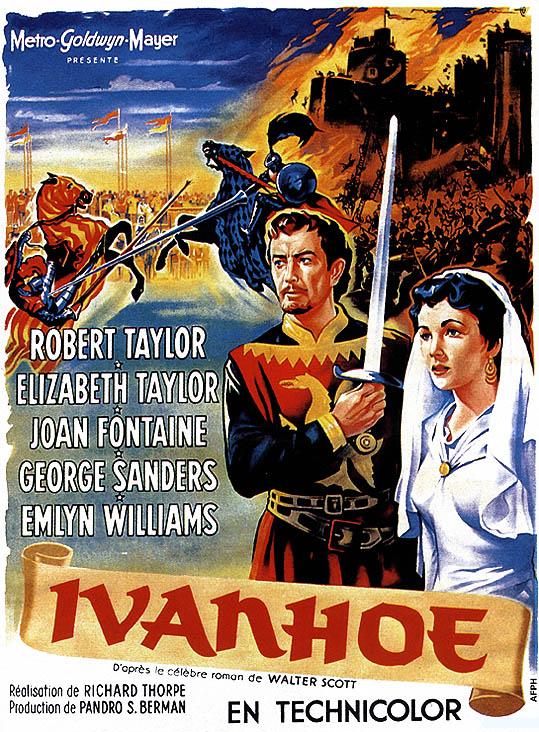

Thackeray, who grew up with Ivanhoe, described as Rebecca “the sweetest character in the whole range of fiction,” and published a fantastical sequel, Rebecca and Rowena (1850) in which she and not the “icy, faultless, prim” Rowena marries the knightly hero Ivanhoe. A century later, actress Elizabeth Taylor gave a memorable portrayal of Rebecca in the popular screen version of Ivanhoe.

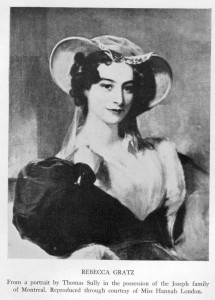

As a fair, kindhearted and eloquent daughter of Israel, Rebecca shines as a model of “true Jewish womanhood, faithful in the defence of her people, her religion and her honour,” writes Montagu Frank Modder in The Jew in the Literature of England. Rebecca “endures the hardships of her lot with calm resignation and extraordinary religious faith,” Modder notes. “As she moves through the story, we admire her dark beauty of raven hair and flashing eye, her modesty, dignity and courage.”

Scott, like Shakespeare, probably did not know any Jews except through legend or hearsay. It was a German friend of his wife’s who suggested that some Jewish characters would lend atmosphere and spice to one of his plots. But it was the American writer Washington Irving who, during a visit to the author of the Waverley novels in Scotland in 1817, specifically inspired the character of Rebecca by telling him about his lovely and charming friend, Rebecca Gratz of Philadelphia.

Seeing that Scott was intrigued, Irving gave a full description. Rebecca, he said, was the beautiful unmarried daughter of a prominent deceased merchant. Besides running her family’s large household, she helped the poor, visited the sick and performed many other charitable deeds; she also ran a school for Jewish children. Those close to her knew that she had been in love with a Gentile man but had sacrificed the romance out of loyalty to her faith. (Irving, too, had lost a young love; his fiancee Matilda Hoffman had died at 18 and had been Rebecca’s best friend. He had been a frequent guest to the Gratz mansion, so much so that a room had been named in his honour.)

“I will make something of your Rebecca yet,” Scott reportedly told Irving. Sure enough, two years later Scott mailed him an early, freshly-minted copy of Ivanhoe with a note: “How do you like your Rebecca? Does the Rebecca I have pictured here compare well with the pattern given?”

Rebecca of Philadelphia must have been immensely flattered by the portrait in Ivanhoe but out of modesty preferred to avoid discussion of the connection between herself and Rebecca of York. However, one Saturday in synagogue a prominent guest asked her, “Is it true, Miss Gratz, that you are the Rebecca of Ivanhoe?” The elegant and legendary figure replied, “They say so, my dear.”

When her sister Rachel died, Rebecca took over the raising of her six children, and delighted in becoming a second mother to many nieces and nephews. She was also a soothing and comforting presence in countless sick rooms, including that of her grandfather. Day after day she sat with him, nursed him, read to him; now, as the end drew nigh, he asked what he might do for her. “Forgive Aunt Shinah, grandfather — please,” she replied, referring to her mother’s sister who had married a Gentile surgeon. With a sigh the old man consented to permit his exiled daughter to visit him; according to legend, he died in her arms as Rebecca sat silently weeping in a corner.

Rebecca’s fame as “an intelligent, gracious hostess, the central figure in a circle of charm and wit and beauty,” only intensified over the years. She died in 1869 at the age of 88. Her story has been told many times; a thorough account of her life is presented in Rebecca Gratz: A Study in Charm, by Rollin G. Osterweis.

Rebecca’s fame as “an intelligent, gracious hostess, the central figure in a circle of charm and wit and beauty,” only intensified over the years. She died in 1869 at the age of 88. Her story has been told many times; a thorough account of her life is presented in Rebecca Gratz: A Study in Charm, by Rollin G. Osterweis.

It was Rebecca’s brother Hyman, whose bequest established Philadelphia’s well-known Gratz College. And it was her niece Sara, who through her marriage to Jacob Henry Joseph of Montreal, established a connection between the Gratzes and the distinguished Joseph family of Canada.

A voluminous correspondent to many notable figures, Rebecca left a large collection of papers to her Montreal niece, Sara Gratz Moses Joseph. Montreal genealogist Anne Joseph has made a detailed study of the Gratz-Joseph connection in her 1995 book Heritage of a Patriarch. The important Rebecca Gratz collection remained within the Joseph family until 1954, when it was donated to the American Jewish Archives in Cincinnati. The elegant portrait of Rebecca Gratz by American artist Thomas Sully is also a Joseph family heirloom. ♦

© 2005