For years the magazines sent him rejection letter s, inferring that his short stories about a pair of Jewish cloak and suit makers in New York were about as unmarketable as last year’s suits and dresses.

s, inferring that his short stories about a pair of Jewish cloak and suit makers in New York were about as unmarketable as last year’s suits and dresses.

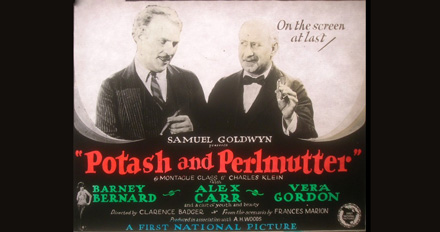

But in the early 1900s Montague Glass broke through to the big time as major American magazines like The Saturday Evening Post and Cosmopolitan began clamouring for his tales about Potash and Perlmutter, a pair of lovable schlemiels in New York’s cut-throat schmattah trade. The duo’s hilarious business misadventures eventually translated into a string of popular movies, radio dramatizations and stage-plays that broke attendance records in both New York and London.

Born in Manchester in 1877, Glass came to New York at age 12 and studied at City College. He trained as a lawyer and joined a Jewish law firm that represented many of the immigrant garment factories that were a dime a dozen on the Lower East Side. The experience gave him the ability to write about the tailoring milieu from the inside — a world that, for anyone else, would have seemed far too common to be glamourized in fiction. Glass’s heroes, Abe Potash and Mawruss Perlmutter, are so ordinary, and their business surroundings so mundane, that their very representation in literature is already cause for laughter.

Bookman, a literary journal, praised the 1911 collection Potash and Perlmutter: Their Copartnership Ventures and Adventures for its “photographic sketches of Hebrew types found on the East side of New York,” adding that Glass’s various characters — cutters, designers, travelers, bankers, lawyers, fashion models, factory owners — occasionally seem as vivid as “Pickwick, Becky Sharp or Falstaff.”

“They come to us dripping with faults; they shock us by their manners and their meannesses, by their money-lust and sharp practice; but they grow on us until we accept them as relatives — that is, we see their faults merged into a universal humaneness, a humaneness that we share ourselves.”

“Mr. Glass blazes a trail of his own in current fiction by presenting certain types of Jewish business men who appear to us as real human beings and not caricatures,” the New York Times noted in 1912, when the volume Abe and Mawruss appeared.

In one story, Mr. Siegmund Lowenstein, proprietor of a Galveston dry-goods company, wants to place a large order, using the fact that he has also visited the rival house of Garfunkel and Levy as leverage. “I looked over their line and I may place an order with them, although they ain’t got too good an assortment,” he says.

“Far be it from me to knock a competitor’s line, Mr. Lowenstein,” Perlmutter replies, “but I honestly think they get their designers off of Ellis Island.”

Garfunkel and Levy have a more generous credit policy, a fact that Lowenstein uses to persuade Perlmutter to extend his credit terms from the usual 30 days to 90 days. “The house what gives me the most generous credit gets my biggest order,” he says. Despite the certain knowledge that Potash will be aggravated, Perlmutter closes the deal.

Glass depicts cloak-and-suit operatives as being capable of engaging in friendly truces while still remaining fierce competitors: “While they cheerfully exchanged credit information from their office files they maintained a constant guerilla warfare for the capture of each other’s customers.” But in this case Abe Potash acquires information all on his own that Lowenstein is untrustworthy.

While on vacation, Potash visits his brother-in-law Hyman Margolius, an auctioneer in Pittsburgh, and helps him unload a huge consignment of garments purchased at distressed prices. To Potash’s astonishment, the shipment consists of his own company’s plum-coloured Empire gowns. The seller is “a feller called Lowenstein in Galveston,” Margolius explains. “He wrote me he was overstocked.”

Surmising that Lowenstein is planning to declare bankruptcy and stiff them of their money, Potash wires his partner not to fill the bulk of Lowenstein’s order. Thus the episode ends well for the duo, who remain largely unscathed when Lowenstein indeed declares bankruptcy and absconds to Mexico. But in their continuous bid to outsmart their competitors and customers, they are often foiled.

In one story, they quarrel over the practice of selling single garments below cost to friends, but Abe finally allows Mawruss to discount an Empire gown to his wife’s servant-girl, Lina. The hefty Lina squeezes inelegantly into the dress just as a major client, who had ordered hundreds of the garment that morning, returns to finalize the purchase. Seeing Lina, he abruptly changes his mind and flees the show-room.

In the capable hands of Montague Glass, who quit lawyering to work full-time as a writer, such unlikely material easily becomes the stuff of literature and stage comedy. Glass felt that he was able to see the dramatic possibilities of New York society because he was an outsider due to his English birth. His ironic characters are presented in a realistic and comic light: they are Jewish knights locked in combat with untalented designers, shifty suppliers and cantankerous labour unions.

Glass rightly considered his representations of Jews to be a sharp improvement over the gross caricatures that had been common in vaudeville. But surprisingly, he believed he was writing in a romantic vein; instead, along with writers like Abraham Cahan and Anzia Yezierska, he was one of the early American Jewish realists who sought to portray their subjects not idealistically but as they really are.

Glass, who died in 1934, is largely forgotten today; most of his works are out of print and many of the movies they inspired have disintegrated into dust. However, the Arno Press reprinted a volume of his stories in 1975 and another collection is available for free as an e-book on the internet through Project Gutenberg; visit www.gutenberg.org for details. Aficionados of Jewish writing will find the stories old-fashioned but highly entertaining. ♦

© 2006