From the Toronto Star Weekly, March 25, 1911

EVOLUTION OF TORONTO’S MANY SHACKTOWNS —

PIONEERS HAVE MADE GOOD WITH A VENGEANCE

Between life in The Ward or in the locality of Eastern avenue and life in the poorest district in the outskirts there is an immense difference. In the Eastern slum people are living in filthy conditions and abject poverty. In The Ward there is not so much poverty. That is to say, there are many people there with money enough to better themselves if they choose. Property owners there, many of them, hold valuable land on which are miserable hovels, which they will not improve in the slightest degree. The owners are content to live in filth themselves. Land was advertised this week on Chestnut street at $175 a foot — twice the price of choice lots in Rosedale. And owners and tenants alike are crowded together in huts on this valuable land — crowded together close enough to produce a fair revenue from the property.

The outskirt dweller gets away from all this. His wholesome desires have a chance to develop. The slum-dweller has sewers at his door, but he does not use them — many houses in The Ward having no drain connections. The dweller in the outskirts has no sewers, but he wants them. He is fighting for them, and will get them. Some day, too, he will have good street car facilities, let us hope. In the meantime he has fresh air, and the sanitary conditions in which he lives are as good as those of a small town. The slum-dweller is in a slough of despond. The dweller in the outskirts is making headway towards a competence and is hopeful of the future.

They Have Made Good.

The cheap-home population on the city’s borders is at least 30,000. Our Shacktowns — still so called for want of a better name — have certainly made good.

The movement under consideration began between five and six years ago. Newcomers from the Old Lands were flocking to the city in great numbers. Those without money had to live down town in poor hovels. They were driven to The Ward and the slums of the east end. So when opportunities were opened to them of buying cheap land in the outskirts thousands of them made the attempt to become homeowners. And not a few native-born residents saw the wisdom of the movement and joined the exodus. The sight of the little tar-papered shacks they built was at first considered pathetic. Then as the movement grew it was looked upon as ominous. “These people,” it was predicted, “will spoil the outskirts of the city for all time. Conditions will soon be as bad up there as they are in The Ward.” But let us see what resulted.

Earlscourt a Winner

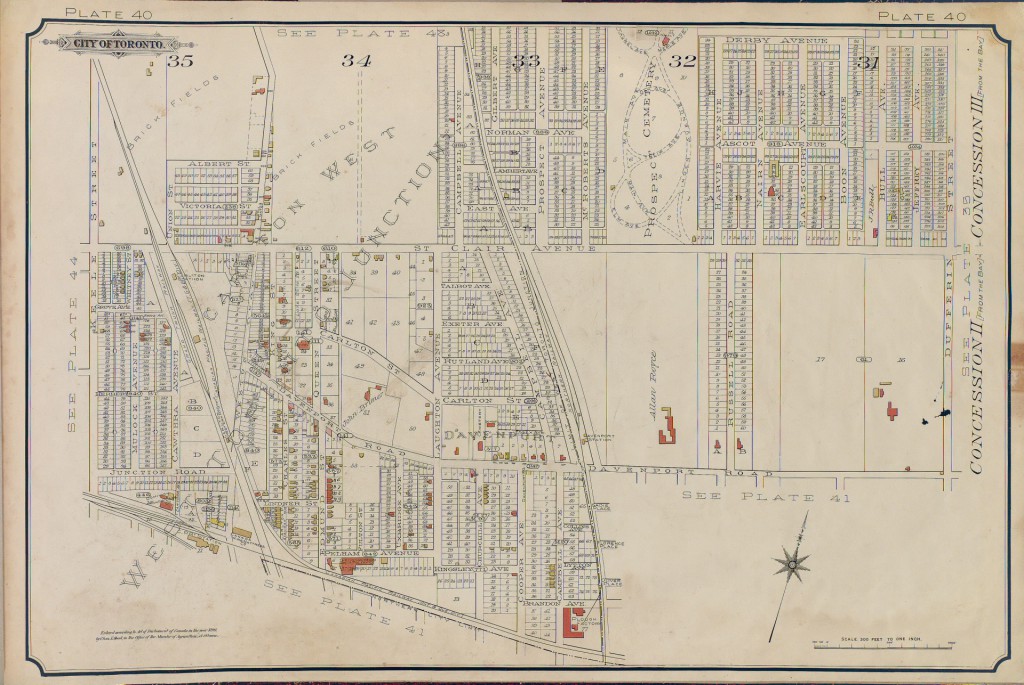

Take Earlscourt, for example, it is located east of Prospect Cemetery, which runs from St. Clair avenue north to Eglinton avenue, east of the G.T.R. and the Canada Foundry.

This district was put on the market a little over five years ago by Robins Limited. It was sold in 25-foot lots, although in most cases the buyers took fifty feet. Prices ranged from $6 to $13 per foot, and therms of purchase were $5 down and $5 a month on each 25-foot lot. The land was taken up by English, Irish, and Scotch working people. Today, it is worth from $20 to $30 a foot, and the owners have their titles clear. Many of them made their last payments long ago.

Mr. Fred B. Robins, when asked about the Earlscourt people this week, was enthusiastic in praising their industry and their fine steadiness of character. “They had a hard time of it in 1907, but they came through the depression with great grit. They all met their payments eventually, and most of them didn’t wait to settle by the instalment plan, but cleared their properties of debt away ahead of time.”

It was during the winter of 1907 that “bad times” came upon the whole continent. Many of the Earlscourt men were thrown out of employment. They couldn’t make their payments. But the company carried them over, and as soon as they got work they made good. But many a tale of hardship is told by collectors and others who were acquainted with the locality at that time. One of these stories will illustrate what some of these worthy citizens went through.

A Tale of Hard Luck

A man and his wife, with one child, bought an Earlscourt lot and put up a shack. Three years ago when $100 had been paid on the fifty feet purchased the husband died. The wife went out washing, neighbours aiding in caring for the child in her absence. Then she broke her arm and finally had to have it taken off. She was in the hospital three months. She could not make a payment on her land for a year. Yet somehow she overcame her difficulties. She has her lot paid for, and the collector who told the story in a sober voice added that he had seen her lately cheerfully doing her work with one arm. So much for the heroism of the poor.

Earlscourt proper is now part of the city, and it cannot now be fairly called a shack district, except that it began that way. Additions have been added to the first tiny structures, some have been bricked, and the locality is one of tidy cottages, inhabited by good, highly self-respecting citizens. There is excellent school and church accommodations there. The Ratepayers’ Association of Earlscourt is alert and active in seeking sanitary and other improvements. The district, indeed, is a model of its kind — its sturdy population of 500 an unanswerable argument in favour of cheap land for cheap homes in the outskirts.

Where the 30,000 Live

It has been said that at least 30,000 people are living on the borders of the city in their own little homes as a result of the exodus described. The various large districts and their population are as follows:

Swansea vicinity, 2,000 people. The poorer part of this district is improving fast, the original shacks being rapidly displaced, and it will soon be no unfit neighbour of the high-class section.

Dufferin Heights, west of Dufferin to Eglinton Avenue, 100 acres, 50 people.

Prospect Heights, west of Prospect Cemetery, 36 acres, 500 people.

Earlscourt, 70 acres, 500 people.

Nairn Estate, north of Earlscourt, 125 acres, 1,500 people.

Parsons Estate, north of Nairn, 200 acres, 1,000 people.

Toronto Heights, west of Parsons Estate, 25 acres, 500 people.

St. Clair Annex, 50 people.

Lakeview Heights, north of Ossington avenue, above St. Clair, 75 people. This section had a record-breaking sale a year ago last October, when 121 lots were sold in two hours and a half, the price $8 a foot. The land is now worth $15 a foot.

Kenwood, west of Bathurst and north of St. Clair, and Wychwood, east of Bathurst and south of St. Clair, 160 acres, 3,000 people.

Lakeview Annex, farther north, where Vaughan road cuts Eglinton Avenue; unbilt on, and improving in value.

Bedford Park, between Bathurst and Yonge, 120 acres, 400 people.

Northern Heights, east of Yonge, 200 acres, 500 people.

Moore Park, with 350 acres and 1,000 people, cannot be included as a shack district, although often so referred to.

East Toronto vicinity, 10,000 people.

York Height, north of the Kingston road, 60 acres, 300 people.

Exclusive of Moore Park, this brings the number to 30,575, but many people have built shacks or tiny cottages outside the large districts named, so that 30,000 is a conservative estimate of the total number.

Live Within Their Means

Nearly all these people are of our own blood. Many of them are no poorer in money or character than the grandparents of some of the social notabilities of today. Many of them also, if they only knew, could have the laugh on thousands of citizens in apparently much better circumstances. For the poorest shack-dweller is a home-owner. He goes, too, on a sound rule of economics. He lives within his means. Only about fifty per cent of the people who have bought land in the districts mentioned have built thereon. Many of the late-comers are waiting until their land is paid for, when they can float loans to erect homes. And these houses, when built, will be of a much better class than the shacks of the pioneers. The real shacks were the work of their owners. If a man in his spare time could erect a place in which to accommodate his family he could live on his property before it was paid for. A very little money would buy the necessary material. When his circumstances improved, he improved his house, putting a front on his shack or using it for a woodshed. But the man who had to employ labour for building had to wait to get a clear deed in order to raise a loan.

A Comparison

How much better off is the family of an owner of a little home in the outskirts than that of a man who rents a cottage or cheap rooms downtown Here is an actual example in comparisons. Two Englishmen in poor circumstances arrived in Toronto a few years ago. Both wee painters, with families. They each rented poor rooms in the heart of the city paying about $8 a month. When they had each saved some $30, one man bought a lot in the outskirts, built a shack and moved in. The shackman had his troubles but is getting along. He owns something. He lives in the fresh air. The other man’s wife recently had to pawn her wedding ring to pay their room rent, and they live in one of the places described by Dr. Helen MacMurchy, where one broken, outdoor water-tap serves several families. ♦

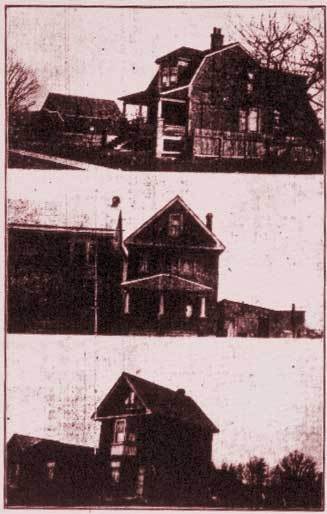

◊ Photo caption –The Development of Earlscourt: The photographs made in Earlscourt this week show the various stages of development there. The brick house in the bottom picture is a typical better-class residence. The owners’ abandoned shack is at the rear. The next one shows how rows of good houses are springing up. In the top picture is seen a still better house contrasted with the builder’s first shack — Earlscourt past and future.

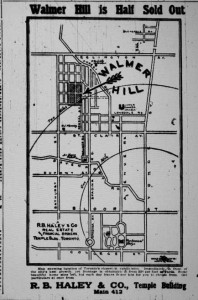

◊ Map below shows location of Earlscourt district. Courtesy Toronto Public Library