This article, which appeared under the title “Gone to the Movies” in the Canadian Jewish Standard of March 14, 1935, tells the sad tale not only of the demise of the Standard Yiddish Theatre at Spadina and Dundas in Toronto, but of the Yiddish language in general across North America. Younger, more assimilated and acculturated audiences were not as keen to see the old Yiddish melodramas so reminiscent of the “alter haim” across the sea — not when they could go and see a Hollywood movie. Beyond its sociological analysis, the article — written by Vincent Geller — is historically valuable for the information it provides about the early Yiddish theatre in Toronto.

This article, which appeared under the title “Gone to the Movies” in the Canadian Jewish Standard of March 14, 1935, tells the sad tale not only of the demise of the Standard Yiddish Theatre at Spadina and Dundas in Toronto, but of the Yiddish language in general across North America. Younger, more assimilated and acculturated audiences were not as keen to see the old Yiddish melodramas so reminiscent of the “alter haim” across the sea — not when they could go and see a Hollywood movie. Beyond its sociological analysis, the article — written by Vincent Geller — is historically valuable for the information it provides about the early Yiddish theatre in Toronto.

* * *

When the old Standard Theatre succumbed to a long siege of apathy, under-nourishment and cold feet, and closed its doors as the home of Yiddish drama in Toronto, no one, except for a handful of bereaved showpeople, was visibly affected by the loss and no one came to say “Kaddish” for the departed. If anything, the handful came to bury the theatre, not to praise it, and it passed into limbo unwept, unhonored and unsung.

Commercially, the building had been a white elephant from the start, and during its fourteen uncertain years, seven of which had been lean ones and the remaining seven leaner, the number and calibre of its patrons dwindled and withered to a point where, to say the least, liquidation was inevitable. The inconsiderable body of playgoers, furthermore, was divided into smaller factions, each with its own opinions on the social and cultural significance of a theatre and each dissatisfied with the existing policy.

On the other hand, the harangued and distracted management did its utmost to placate all opposition, but every attempt to stem the decline only served to increase the ranks of the malcontents. There was something fundamentally wrong somewhere and no palliative, not even the new wine-colored curtains, could put the theatrical Humpty Dumpty together Again. When the news broke that the Yiddish stage was through in Toronto, the restaurant intelligentsia shrugged their shoulders as if to say that the report of its death was highly overdue and that, as far as they were concerned, rigor mortis had set in years before.

* * *

THE strange history of the Jewish Standard Theatre in Toronto could be briefly reviewed with the aid of a chart indicating the various phases in the struggle between two generations and two languages, and the rapid gain of the vernacular of the land during the past few years. Yiddish is itself at comparatively young language and the Yiddish Theatre as a permanent institution began with Goldfaden about 1875. But the mother-tongue and its colorful drama are beating a fast retreat and the horizon reveals no legions of new supporters coming to the rescue. And the intellectuals, the Yiddishist literati, will have no truck or trade with the Jewish stage unless it can undertake the dignified, creative programme which their criterion

THE strange history of the Jewish Standard Theatre in Toronto could be briefly reviewed with the aid of a chart indicating the various phases in the struggle between two generations and two languages, and the rapid gain of the vernacular of the land during the past few years. Yiddish is itself at comparatively young language and the Yiddish Theatre as a permanent institution began with Goldfaden about 1875. But the mother-tongue and its colorful drama are beating a fast retreat and the horizon reveals no legions of new supporters coming to the rescue. And the intellectuals, the Yiddishist literati, will have no truck or trade with the Jewish stage unless it can undertake the dignified, creative programme which their criterion

demands.

But that isn’t all. There are other forces, so far and yet so near, engaged in a titanic competition and between them Yiddish drama has been all but exterminated. To understand its decIine we have only to examine the situation on Broadway where the legitimate show business is laboring under insurmountable disadvantages. One theatre after another has been put on the spot by the radio and the talking picture. Some have closed their doors, others have been turned into clubs. And in their war of the industries the Jewish stage has been the heaviest loser. It has lost its actors, its producers, its public. It is significant that the former Standard Theatre has become a movie palace with Neon-lighted marquee and uniformed ushers. But so much for the business end.

As a social centre and commercial institution the Standard served all cliques and organizations. Conveniently located at the corner of Spadina and Dundas, where boss and worker mingle with rabbi and atheist, the theatre stood as a symbol, a temple where all could enter and worship as they pleased. Labor unions frequently met here to choose between strike and status quo; Zionists gathered here to hear the reports of their leaders; worshippers converted the theatre into a synagogue for the High Holy Days; politicians made generous promises at election meetings; there were simple but enthusiastic receptions to visiting poets, leaders, lecturers. Last but not least there were gala benefit performances, given under the auspices of popular lodges, when the matronly president of the Ladies’ Auxiliary would appear on the stage after the second act escorted by a committee and there would be much eulogizing and thanking all around. The theatre was often the setting for plays that were quite as authentic as those included in the repertoire, and the audience caught the spontaneous rhythm of a Jewish crowd at home. When you gave your ticket to the doorman, you were admitted into a classless society.

The main events of the week were Friday night, Saturday night and ladies’ night. The plays in most cases, stressed character delineation, with little emphasis on the sociological and artistic element. This work was left to visiting celebrities such as Schwartz and Ben Ami. Such themes as mother love, filial ingratitude and juvenile delinquency were tops. The first act would take place in a Russian village and the last two in the East Side or the Bronx. There had to be plenty of song and dance spectacle, with the result that many a play was transformed into a minor musical comedy, and plays that would not lend themselves to such adaptation could not be produced. The songs had to be timely and familiar, so that a score like “Remember My Forgotten Man” became “Vu Bist Du Yiddisher Soldat?” Sometimes the transformation wasn’t so ingenious. But the troupers tried hard and when they were expected to act, they did so with a vengeance. Let it be said that their leading ladies, when given the opportunity, showed that they were something more than mere cigarette advertisements.

* * *

THE neighborhood was a quilt of many colors. The Spadina-Dundas intersection became in time an unofficial Red Square. Farther down was the chaotic garment area. Across the street the Labor Lyceum, home of the twelve tribes of toil. Near by was the crowded Kensington Bazaar. To the north, the College Street promenade, everybody’s college. East, west, all around the theatre were change and activity, crystallization and sundering, the heterogeneous lives ofa homogeneous people. A phenomenon our neighbors have marvelled at but never understood. And there stood the theatre growing more forlorn from year to year; becoming less of a playhouse and acquiring the earmarks of a landmark.

THE neighborhood was a quilt of many colors. The Spadina-Dundas intersection became in time an unofficial Red Square. Farther down was the chaotic garment area. Across the street the Labor Lyceum, home of the twelve tribes of toil. Near by was the crowded Kensington Bazaar. To the north, the College Street promenade, everybody’s college. East, west, all around the theatre were change and activity, crystallization and sundering, the heterogeneous lives ofa homogeneous people. A phenomenon our neighbors have marvelled at but never understood. And there stood the theatre growing more forlorn from year to year; becoming less of a playhouse and acquiring the earmarks of a landmark.

The appearance of a major actor or the production of a better play always brought the old guard back. Good houses ,were not unexpected when the company undertook to do “Mirele Efros,” “Nora,” or “The 7 That Were Hanged;” and the native audience was frequently augmented by a large non-Jewish attendance. The last production of “Nora” attracted a Gentile following that accounted for over thirty per cent of the entire turnout, most of them students and young intellectuals. During its final season the theatre hired a publicity man to keep the non-Jewish press in touch with its important offerings, and Yiddish plays received considerable attention from the Toronto critics. The Yiddish Art Theatre players had many friends here and the stage door was always besieged with pals and admirers calling for their friends. After a performance they would get together in a near-by restaurant and drink the traditional cup of midnight coffee. Then they would run off to a party (for in the show world 2 a.m. is as 2 p.m.) The social life that grew up around the theatre attracted a set of brilliant young people and their sessions with the actorssparkled with gaiety and wit.

* * *

IT WAS a grand old institution, the Standard. Years ago, when the Jews had no theatre of their own, plays were produced in an old negro church on University Avenue, rented for the occasion. Then came the Lyric Theatre, later the National, managed by Max Shore. The National gave way to a garage which was replaced by the present Ford Hotel. When the Standard arrived Mr. Shore, now a veteran, took charge of the box office, and was probably the only showman in town who knew all his customers by name and knew where they preferred to sit. Events of singular interest often took place backstage. There were quarrels between the actors over the assignment of roles, or between the actors and the prompter. Sometimes a temperamental Thespian refused to attend rehearsals, and there were cases where an important member of the cast deserted his company and left for New York without a word of warning. There was the unhappy evening when a tense episode in a play starring Ben Ami was ruined by the collapse of a prop representing a street lamp. Last year the Yoshe Kalb company (while playing at the Royal Alexandra) was threatened with a strike by locally hired supers who swore they would shave their false beards and picket the show unless their demands were accepted. Then there was the disgruntled old actor, a celebrity of another day, who left his troupe and tried to produce his own plays in an old Spadina hall, but the attempt never became an achievement. For a while he lingered around the Spadina haunts and finally went away in quest of happier hunting grounds. So it goes . . . .

It was a grand old institution, the Standard. Its faults and its critics were many, but for all that there was something invisibly nice about it. The boy with the basket of chiclets, chewing gum, chocolate bars, was as much a part of the complete organism as the trouper who appeared in front of the curtain at the end of the second-last act to announce the bill for the coming week. The ushers weren’t concealed in uniforms like wooden sentinels and it was easier to ask them a question. The play was the thing, but it wasn’t the only thing.

Well, the old disorder changeth, yielding place to the new disorder. Even a theatre can turn prematurely grey. The Yiddish drama has gone to the movies. ♦

See also Opening of the Standard Yiddish theatre, 1922

Photo captions:

Top: Scene from Boris Thomashefsky’s famous production of Ossip Dymow’s The Eternal Wander, in the National Theatre of New York, 1913. From left: Gershon Rubin, Boris Thomashefsky, Charles Nathanson, Celia Adler, Bina Abramowitz, Jacob Ben-Ami, Lazar Fried, Rebecca Weintraub, Zigmund Weintraub.

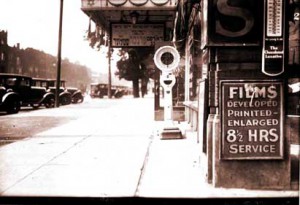

Middle: View of the Standard Theatre from the sidewalk, Spadina and Dundas, Toronto, in the 1920s. Courtesy City of Toronto Archives (citation to follow).

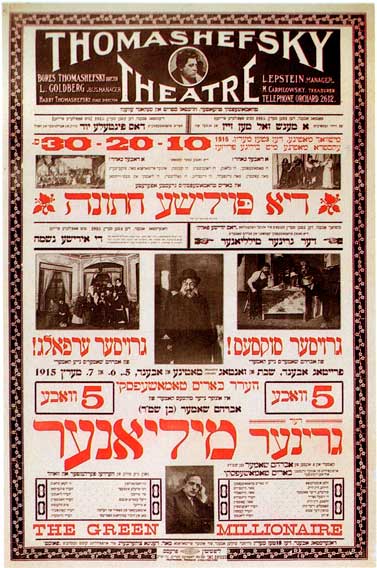

Bottom: Poster for the Thomashefsky Theatre, New York, 1915.

* * *

Emotions flowed across footlights at Yiddish Theatre

Vincent Geller was the press agent for Toronto’s Standard Theatre in 1933 and 1934, immediately before the 1,200-seat Yiddish playhouse was transformed into a movie palace; it later became the Victory burlesque house. The following has been paraphrased from his book, Say T’rawna, published in 1984 when the author was 73 years old.

* * *

The old Standard Theatre, at the corner of Dundas and Spadina, was frequented by all facets of the community. Its open door stood as a symbol and all could enter.

The plays were seldom of high artistic character. Their themes dealt with mother love, filial ingratitude and immigrant life. Their first acts were often set in a village in the Old Country, the last two acts in America.

A song and dance number was often transposed between the emotionally charged sequences so that the material would be transformed into a minor musical. If a play didn’t lend itself to such adaptation, it was seldom produced.

The leading ladies of the popular Yiddish stage were expert at summoning forth tears, and producing pathetic sympathy among audience members, who would moan with anxiety at their grievous misfortunes.

The staging of a classic always attracted the intelligentsia and the box office experienced brisk sales whenever Shakespeare, Ibsen or Ansky was the fare. Whenever the celebrated company of the Yiddish Art Theatre visited from New York, there was also a circle of admirers and hangers-on around the stage door, and even the critics were impressed.

Toronto’s first Yiddish theatre was presented in an old church on University Avenue, then in the Lyric Theatre at Bay and Dundas, which was subsequently renamed the National. It was torn down and replaced with a garage, then the Ford Hotel.

Toronto’s first Yiddish theatre was presented in an old church on University Avenue, then in the Lyric Theatre at Bay and Dundas, which was subsequently renamed the National. It was torn down and replaced with a garage, then the Ford Hotel.

The Standard Theatre opened in the early 1920s after a subscription drive drew an enthusiastic response. The theatre was often the scene of disputes among the actors over choice roles. Sometimes a temperamental thespian would boycott rehearsals or, if sufficiently disgruntled, return to New York rather than take on an undesirable part. (Disputes were common in the world of the Yiddish theatre, not just at the Standard. When the spectacular folk drama Yoshe Kalb was booked into the Royal Alexandra, locally hired “supers” threatened to strike unless they received $2 per night plus carfare.)

One actor was supposed to cry out during a favourite tragedy at the Standard that the world was falling apart. The actor played his line perfectly; and, as if in response, a section of the scenery collapsed. It was a moment of indisputable realism.

The Standard lasted 14 years of continuous losses as a Yiddish theatre, but still managed to keep afloat as long as its audience remained loyal. Show people are reputed to have as many lives as a cat, take their losses stoically, and live by the code that no matter what, the show must go on.

But the loss of an audience is the inevitable kiss of death. When the winds of change drifted in the audience drifted away, the Standard’s curtain was forced to come down on a remarkable chapter in the city’s theatrical history. Resurrected as the Golden Harvest Theatre, Toronto’s former Yiddish theatre at Spadina and Dundas has become an important asset for the city’s Chinese community. ♦