Three Minutes in Poland: Discovering a Lost World in a 1938 Family Film, by Glenn Kurtz. Trade paperback, 420 pages. Published 2014 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. www.fsgbooks.com

In the summer of 1938, the author’s American grandparents, David and Liza Kurtz, took a six-week European vacation that included a brief visit to a Polish town, where David shot three minutes of footage — mostly in colour, which was rare for that day — with a 16mm camera.

In 2009, more than 70 years later, Glenn Kurtz discovered the film in a dented aluminum canister in a closet in his parents’ home in Florida. But the film had deteriorated so badly — having “shrunk, curled on itself, and fused into a single, hockey-puck-like mass” — that it could not be projected. Fortunately, some of the images had been transferred to videotape, and when Kurtz saw them, he was amazed and transfixed: he knew the film was important, and that it had to be preserved.

The film showed a vibrant Jewish community in a Polish town in August of 1938, just three months before Kristallnacht and one year before the onset of the war. But what town? Family sources insisted it was Berezne, his grandmother’s ancestral shtetl, but Kurtz had growing suspicions it might be his grandfather’s ancestral shtetl of Nasielsk. In any case, no one could positively recognize any of the buildings depicted in the crowded town square, abuzz with life.

It was only after he donated the footage to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum that Kurtz solved the mystery by finding an old photograph of the Nasielsk synagogue, identical to the synagogue that appears in the film. Museum officials excitedly declared the film to be “unique.” Evidently, while the USHHM’s Steven Spielberg Film and Video Archive has more than a thousand hours of footage, mostly newsreels and other professionally-produced material, it has only 57 hours shot by amateurs.

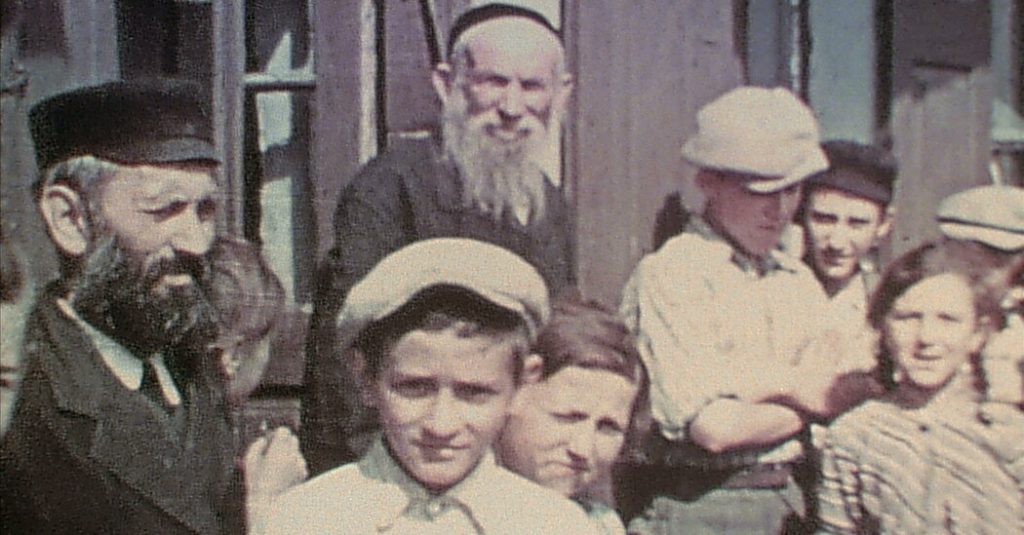

Further confirmation that the town was indeed Nasielsk came after the film was posted online and the son and grandchild of octogenarian Maurice Chandler spotted his grandfather in the film as a sprightly 13-year-old boy wearing a cap. Chandler, who was born in Nasielsk in 1924, was one of relatively few Jews from the town to survive the Holocaust. When his family told him about the film, they told him “you’re in a sea of ghosts.”

That’s a riveting moment in the increasingly dramatic story of how the obsessive Kurtz strives to provide context and identity to the rich, lost and initially anonymous world which has been preserved in those three extraordinary, yet terribly ordinary, minutes of film. The random images — a crowd in the street, workers in ragged clothes, religious men in long black overcoats, women in kerchiefs, a procession leaving a synagogue, and much more — are laden with dramatic irony, since all seem blissfully unaware that their world is soon to be turned upside down and destroyed.

This book chronicles Kurtz’s efforts to restore memory, identity and dignity to nameless faces. It tells how he traveled across the United States and visited Canada, England, Poland and Israel; visited cemeteries, some in decrepid condition; and delved into archives, basements and attics. He eventually found seven survivors from Nasielsk, including two who appear in the film as children. Not surprisingly, much of these discoveries could not have been made without the internet.

Ultimately, through a combination of diligence and luck, Kurtz succeeds in restoring a vibrant picture of Nasielsk’s Jewish community — at least that part of it recalled by a chance group of survivors consulted some 70 years after the devastation. “Nasielsk survives only in memory,” he writes. “But the Nasielsk that exists in memory now is the chance artifact of those who happened to live longest. The memories themselves are equally artifacts of a ruthless process of selection, what is left over after seventy-five years of forgetting, suppressing, reworking, and smoothing out through repetition.”

Kurtz’s story is easily a quest, comparable to such memorable works as Theo Richmond’s Konin: A Quest (1995), Daniel Mendelsohn’s The Lost: A Search for Six of Six Million (2006) and Edmund de Waal’s The Hare with Amber Eyes (2010). Well written and gripping, it is as much about the journey as the destination.