When Russian-Polish immigrant Hirsch Wolofsky decided to launch a Yiddish daily newspaper in Montreal in August 1907, it was clearly an idea whose time had come.

Impoverished Russian-Jewish masses, fleeing pogroms, revolution and war, had begun settling in Montreal in record numbers. Strangers in a strange land, they read New York Yiddish papers like the Forwerts but had no effective way of knowing about their local civic and cultural surroundings.

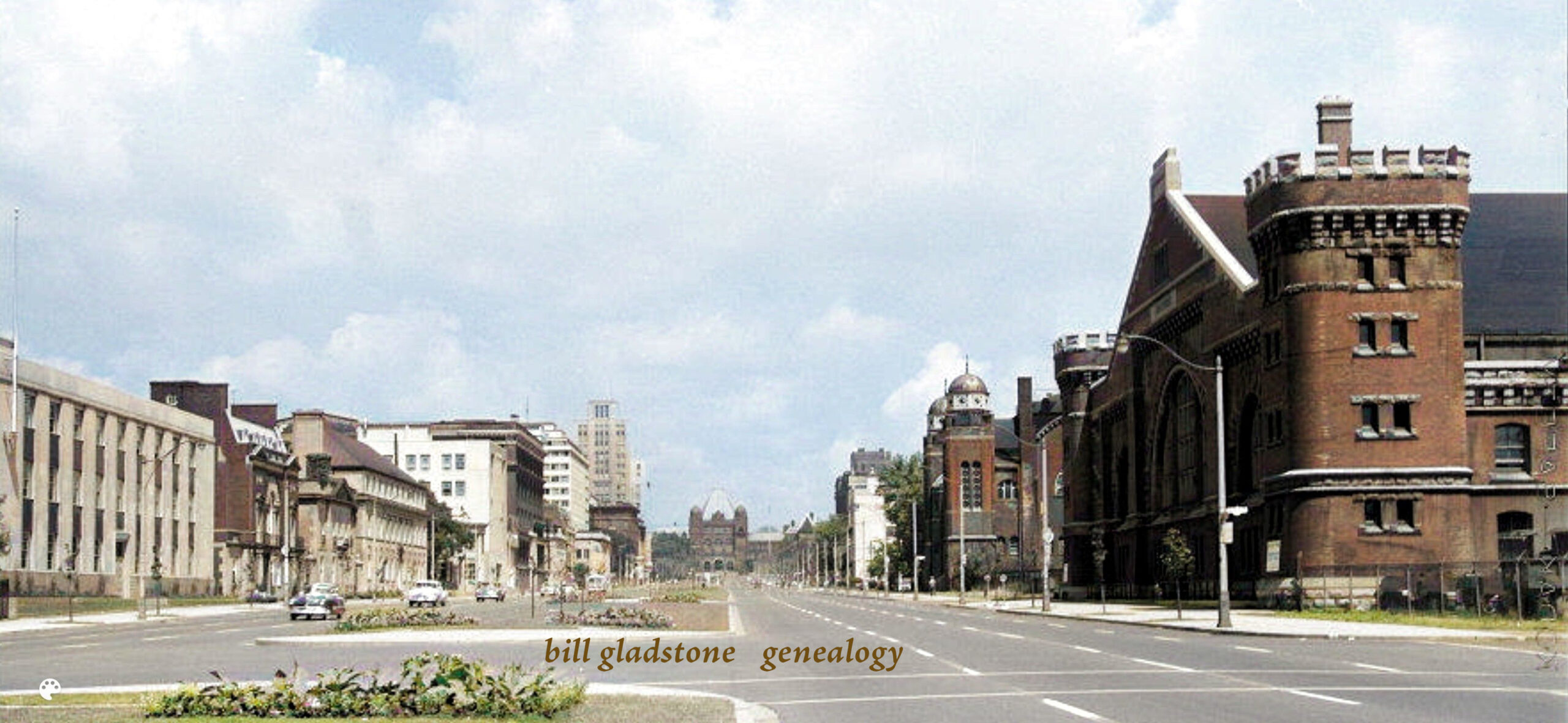

“New immigrants who could not read the English newspapers were ignorant of what was happening in their city,” observed journalist Israel Medres, a distinguished contributor of the new daily. “For them Montreal was a closed book. The Keneder Adler opened that book for them. It revealed to them that they lived in a large metropolis with people of diverse languages, races, beliefs, and cultures.”

A distinctly Canadian, Jewish intellectual voice in the wilderness, Montreal’s Keneder Adler was one of several early Yiddish newspapers that helped immigrants adapt to life in Canada. The “Canadian Eagle,” as its name translates, also fulfilled another vital function by sparking the formation of Jewish fraternal organizations, sick benefit societies, libraries, a national Congress and other communal structures.

Two recent books from Montreal’s Vehicule Press shed welcome light on the almost-forgotten pages of this once-influential journal. Through the Eyes of The Eagle: The Early Montreal Yiddish Press, 1907-1916 offers English translations of a range of pieces by distinguished journalists and editors including Wolofsky, Medres, Reuben Brainin, Isaac Yampolsky, A. M. Mandelbaum, even Sholem Aleichem.

Two recent books from Montreal’s Vehicule Press shed welcome light on the almost-forgotten pages of this once-influential journal. Through the Eyes of The Eagle: The Early Montreal Yiddish Press, 1907-1916 offers English translations of a range of pieces by distinguished journalists and editors including Wolofsky, Medres, Reuben Brainin, Isaac Yampolsky, A. M. Mandelbaum, even Sholem Aleichem.

In articles such as “A Day in the Editor’s Office,” Yampolsky charmingly conveys some of the harried comic flavour of working under constant deadline pressure while being constantly interrupted by members of the public and other nuisances.

A woman enters with a child: “I am asking you to put him in the papers and bury him deep — my husband, I mean. He deserted me two years ago because I was yelling at him, he said. Do I yell? It is only my habit. I speak loudly.” She doesn’t leave until the editor promises to run a photo of her errant spouse in the paper’s Gallery of Missing Husbands.

A rabbi enters: “I will speak in a synagogue on Sabbath, so I’d like you to write something about me.”

Finally, no more interruptions. Yampolsky watches his editor write feverishly: “The pen bends under the speed and races like a fire. If anybody will interrupt him I will throw him down the steps head first.” Yampolsky picks up a pen and follows suit; the typesetters hover, awaiting fresh manuscript pages. “We both write. Writing is like a milk cow. As long as the milk comes, we milk. When the milk stops coming, we milk it anyway.”

Besides much light humour, the volume offers historical material on the city’s Jewish institutions, articles about theatre and politics, even some fiction. The book was a pet project of the late historian David Rome, who made the selections and did the translations, and was knowledgeably edited by Yiddish scholar Pierre Anctil.

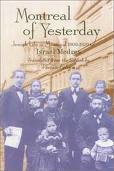

An equally absorbing Vehicule title is Montreal of Yesterday: Jewish Life in Montreal, 1900-1920, by Israel Medres, translated from the Yiddish by Vivian Felsen. Already favourable reviewed in these pages, the book features many articles that originally appeared in the Keneder Adler.

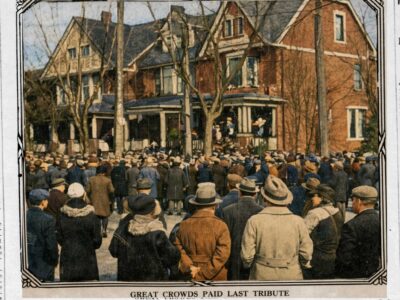

The genealogist asks: did the Keneder Adler publish death notices? The answer is yes. The Jewish Genealogical Society of Ottawa offers a searchable database on its website, www.jgso.org.

The historian asks: did David Rome leave behind any more uncompleted projects? The answer is yes. This month, Montreal genealogist Anne Joseph and archivist Janice Rosen published limited copies of an unfinished treatise of Rome’s under the title, House of Life: A History of Jewish Cemeteries in Canada. The work should be accessible shortly in select libraries and archives. ♦

© 2003