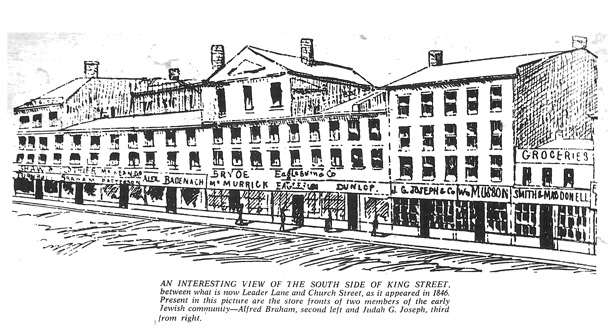

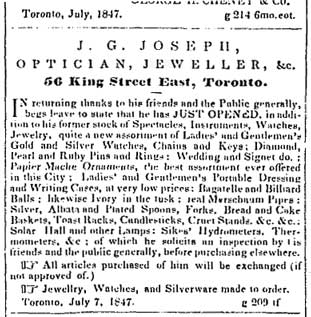

When Judah Joseph, an English-born Jew, settled in Muddy York in 1838 and set up shop as an optician and watchmaker, little did he dream he was the forerunner of a vigorous community of 75,000, the third largest Jewish community in the British Commonwealth.

When Judah Joseph, an English-born Jew, settled in Muddy York in 1838 and set up shop as an optician and watchmaker, little did he dream he was the forerunner of a vigorous community of 75,000, the third largest Jewish community in the British Commonwealth.

It is now (in 1956) celebrating its 100th anniversary as an organized community. In 1856, 17 Jews, including Mr. Joseph, met in a little room over a store to organize Toronto’s first synagogue, now named Holy Blossom Temple.

One of the first things the new congregation did was to arrange for a supply of kosher meat from a Mr. Wickson in the St. Lawrence market. Kosher food is always a first concern of small and isolated Jewish settlements. They arranged for Rev. Hyman Goldberg to come from New York as rabbi and cantor, and as “schochet” as well to supervise the kosher meat supply.

Lewis Samuel, another English-born Jew, was so dismayed at finding no synagogue here when he arrived in 1856 that he was a leading figure in organizing the first one. He established a business in metals which, despite keen competition, stayed closed on the Sabbath and festival days.

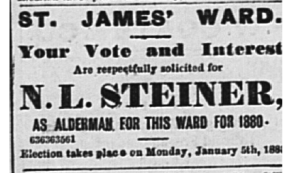

Newman Steiner, a marble cutter, who fought with the insurgents in the Hungarian revolution of 1848, was the first Jewish alderman to be elected in Toronto (1880), obtaining the largest vote ever polled by an alderman. He represented St. James ward for five years. A reformer in politics, he was also the first Jew in Ontario to be commissioned a justice of the peace.

Newman Steiner, a marble cutter, who fought with the insurgents in the Hungarian revolution of 1848, was the first Jewish alderman to be elected in Toronto (1880), obtaining the largest vote ever polled by an alderman. He represented St. James ward for five years. A reformer in politics, he was also the first Jew in Ontario to be commissioned a justice of the peace.

There are now about 70 synagogues in Metropolitan Toronto. One of the new ones of north Bathurst Street was financed entirely by one pious, elderly Jew who sat on a rough box in good weather and bad and watched his beloved “shull” go up brick by brick. He had vowed to build his own synagogue after a disagreement with a congregation downtown.

The growth and integration of the Jewish community into the fabric of the city’s life is a remarkable feat. It is the largest non-Angle-Celtic ethnic group, yet it forms less than six per cent of the total population. It was a trail blazer for immigrants of other origins who benefitted from the existence of a well-adjusted and well-organized minority.

Far from being obliterated or assimilated, the Toronto Jewish community is today enjoying a renaissance in its religious and cultural life. New synagogues and Hebrew schools are springing up in North York where so many young Jewish couples have settled.

Far from being obliterated or assimilated, the Toronto Jewish community is today enjoying a renaissance in its religious and cultural life. New synagogues and Hebrew schools are springing up in North York where so many young Jewish couples have settled.

Attendance at religious services is good. Interest in Jewish books and history runs high. Support for communal organizations for old people, children, the sick and needy is better than ever. The co-operation between organizations representing varying shades or religious orthodoxy and politics is excellent.

While taking their place in the city’s stream of life, Toronto Jews are proud of their history and traditions. The strength they draw from these sources makes them more secure and useful citizens. The community has never wavered in its support of Israel, with which it has ties of blood.

The big wave of immigration was 1911 to 1921, the community increasing by 90 per cent in that decade. The sons and daughter of these immigrants still have vivid memories of the struggles their parents had to make a living in a new land. Even in their lifetime, the children have seen amazing changes. In 1921, less than four per cent of the community lived north of Bloor Street. Today most live in a long swath a mile east and west and Bathurst Street as far north as Sheppard Avenue and beyond.

The big wave of immigration was 1911 to 1921, the community increasing by 90 per cent in that decade. The sons and daughter of these immigrants still have vivid memories of the struggles their parents had to make a living in a new land. Even in their lifetime, the children have seen amazing changes. In 1921, less than four per cent of the community lived north of Bloor Street. Today most live in a long swath a mile east and west and Bathurst Street as far north as Sheppard Avenue and beyond.

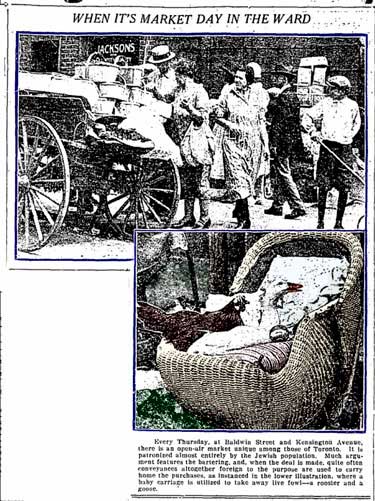

But there are pilgrimages to the old haunts, combining sentiment and shopping. The family piles into the car and heads for “Kensington,” the picturesque area of narrow streets running off Spadina Avenue, south of College Street, where the aroma of fresh baked bread, and palate-tickling odors from jars of dill pickles and barrels of herring are the essence of nostalgia.

(Incidentally, do not underrate traditional Jewish foods and cooking as a weapon against assimilation!)

Fruits and other goods still spill on to the sidewalks from crowded shops. Only a foolhardy motorist will try to thread his way right to the heart of the district. You can still pick out a live chicken.

The centre of Jewish life 50 years ago was in the old “ward,” west of the present city hall. Then Elizabeth Street, Chestnut Street, Centre Avenue and what are now Dundas and Bay Streets abounded with synagogues and market places.

After World War I, a new immigrant wave reached Toronto from the war-torn and pogrom-ridden areas of Poland and the Ukraine. The area of Jewish settlement moved a mile or two westward and northward. Spadina Avenue became the centre for the newcomers and their children. On its side streets, there sprung up dozens of synagogues, educational institutions, Hebrew and Yiddish cultural agencies and Zionist societies.

The immigrants mixed with the older settlers and felt their way in the Canadian scene. Some stayed behind the sewing machines and in the factory and contributed to Canada’s growing trade union strength. Others went into commerce and industry and were a factor in the thriving business of Canada’s second city.

In World War Two, Jewish youth of Toronto fought side by side with Canadians of all origins. The war experience helped break down prejudices sometimes held by both sides.

After the war, the community opened its heart to 1,000 war orphans from overseas and there was a waiting list of homes. The influx of 15,000 immigrants who survived the gas chambers posed another challenge but the community’s resources met the test, as they did for 1,750 internees from Germany and Austria sent to Canada from England, who were released, under sponsorship, for farm work and study.

Some idea of the strength of the Jewish religion is given by the 1951 census which showed that only 340, or less than one per cent, said they were Jews by origin, but no longer by religion.

There is a colorful history to the communal institutions. Many date back to small groups of men and women who came together to fulfill the ”mitzvah” (the divine commandment) to care for the poor, the sick and the forsaken.

In the Hitlerism-charged atmosphere of the 1930s, with Swastika clubs operating at Kew Beach and Christie Pits, it was inconceivable that one day Toronto would have a Jewish mayor. It would be unrealistic to say discrimination has disappeared.

Jewish citizens still run into obstacles in education, employment, housing, and social and athletic clubs. But it has eased. The outlawing of restrictive covenants in 1950 and the anti-discrimination legislation of the provincial government, though not without loopholes, are signs of the times.

The community looks forward with confidence to the next 100 years. ♦