From the Canadian Jewish Review, November 24, 1967

Although Toronto Jewry is either 118 years old (if one estimates its age from the date of the Pape Avenue burial ground) or 111 years old (estimating from the first permanently organized congregation), its relative newness can be gauged by two facts: until only a few years ago Sigmund Samuel, son of the community’s founder Lewis Samuel, was still among us; and Arthur Cohen, 87-year-old son of the Magistrate Jacob Cohen, still among us today, can recall his chederdays when the Holy Blossom was a wooden structure on Richmond Street in what is now virtually the pre-history of the community.

The death a few years ago of Anne Franklin Robinson severed another link with the city’s early Jewish community. Despite this relative newness, factors like the increasing growth of the community, its high mobility and the rapid pace of change and flux threaten to cast much of the earlier strain of development into a state of oblivion.

The new generation growing up in the outer fringes of North York are likely not aware that the Beth Tzedec was comprised of two congregations, both founded in the 1880s and both located for fifty years within three blocks of one another, one on University Avenue and one on McCaul Street – both below Dundas Street.

Nor do they realize that the Adath Israel located near the 401 Highway was until recently the “Rumanian Shool,” founded in 1902, and that the significance of this date is that it comes two years after the famous trek by foot by a group of Jewish fussgehers right across Central Europe from Rumania to the port of Hamburg in the wake of persecution and oppression.

Do they know that in the 1920s and into the 1930s, it was customary for leading rabbis to be associated with several synagogues rather than only one? The late Jacob Gordon was retained simultaneously by the Goel Tzedec, the McCaul Street Shool, the Anshei England and others. This did not imply necessarily that rabbis so retained received double or treble compensation. In fact, the stipends provided were so inadequate that spiritual leaders supplemented their income not only in the usual way of performing marriages, divorces, funerals, etc., but by engaging in business (a practice, incidentally, not frowned on in Jewish tradition, which preferred that he not make a livelihood out of Torah).

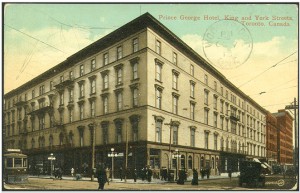

Neither is it well known that the Prince George Hotel at King and York Streets was built by two Jewish brothers named Rossin and was known as the Rossin House.

The Nordheimer Ravine, now being bisected and despoiled by the Spadina Expressway, is named after a family that came to Toronto in the 1840s who were music teachers to the Governor’s family. One of these brothers, Abraham, returned to Germany where he died and the other, Samuel, though he was baptised an Anglican and married into the Family Compact segment of the city’s upper crust, always took occasion in public documents to mention his Jewish ancestry and continued to give to Jewish causes.

In these days of dialogue and ecumenism, it is doubtful if the rising generation realizes that the burning question between the faiths in the pre-World War One period and after, was the Christian missions to the Jews (many of these conducted by converted Jews) and the aggressive methods they pursued to attain their ends.

In 1911 Solomon Jacobs, then rabbi of Holy Blossom, delivered a sermon in the severe cathedral language of the day in which he scolded the Presbyterian Church for its soul-snatching campaign, urging instead that it save the “fallen women” and the derelicts of its own faith and leave the Jews alone.

What of the stormy ideological struggles that took place in the working class of Toronto Jewry in the late 1930s when the mass of the community consisted of Yiddish-speaking immigrants? The fight within the furriers union was settled by crowbars and knuckle irons, and the Labour Lyceum on Spadina Avenue was a labour market, a political Rialto. The sidewalk in front of it was a hub of political discussion, as were all the restaurants and kibetzarnias up and down Spadina Avenue.

The area of first settlement of Toronto’s East European Jews was the Ward – the district bounded by Bay Street and University Avenue, Queen Street and College – a segment of town they shared with the Italians (then a much smaller group than today) and within this area – later to be identified as Chinatown – were at least half a dozen synagogues. Even in the 1930s, strikers picketing a kosher poultry business bore trilingual placards – in English, Chinese and Yiddish.

Would it mean anything to the younger generation to know that Emma Goldman, the renowned (or if you will, the notorious) anarchist spent her last few years in Toronto – she was considered too “dangerous” to re-enter the United States where she had lived since the age of seventeen. She delivered several lectures at the Labour Lyceum in 1939 in the archaic and stilted Germanized Yiddish that was affected at the turn of the century by radical speakers, expressing her disillusionment with the statism and repression of Soviet Russia and re-affirming her continuing faith in libertarian anarchism.

The Holy Blossom Temple in its Bond Street stage was then popularly known as the Deutschisher Shool (German synagogue) not because of any German origin – its founders were mainly English – but because of its style and outlook. Its posture of modernism was known to East European Jews as “German.” (This was before Hitler gave the adjective other, more tragic, connotations.)

Are the youth of today aware that back in 1897 a young doctoral student of political science while earning money to pay his graduate school fees at Harvard and Chicago, did some summer newspaper work on the “foreigners” of Toronto with a section on the Jews? The young man, William Lyon Mackenzie King, was to become Canada’s Prime Minister twenty-three years later. He made a rather keen analysis of Toronto’s 2,500 Jews of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee years: their occupations, their background, their zest for education, their intense religious zeal and their seriousness about making Canada their permanent home.

Other events occurred that year: the Holy Blossom Synagogue, referred to more often than not as the Toronto Hebrew Congregation, left its Richmond Street frame building and moved into a new building on Bond Street described by the young Mackenzie King as “an edifice which testifies more forcibly than words to the religious zeal of the Jewish people and to the place which they hold in the community today.” He went on to say “while it is unquestionably one of the finest structures in Toronto, it also is one of the very few of the many churches in the city which are without a cent of debt.”

The Bond Street structure (which now serves as a Greek Orthodox Church seventy years after its erection, a denomination for which its Byzantine domes are particularly appropriate) was used by the congregation for forty years. In 1937 the present building on Bathurst and Ava Road was built. The two antecedents of the Beth Tzedec were each used for fifty years. How long, one speculates, will Jewish mobility permit the present synagogues to be useful in their current locations?

And what of these, too:

• the May Day parades

• the little girls from the Jewish Sunday School decked in flowers parading before Chaim Weizmann;

• the “Jesus Saves” open air addresses by the Reverends Bregman and Zeidman delivered in Yiddish in a Talmudic sing-song

• the patriarchal grandfather figure of Edmund Scheuer

• the Ward Four Catholic and Protestant aldermen who started their speeches by the stock phrase “Breeder und Shvester”’

• the stars of the Yiddish stage – the Adlers, Herman Yablokoff, the Hollanders, Gehrmans, Muni, Weisenfruends, Morris Schwartz, Jacob ben Ami – who performed at the Standard Theatre (now the Victory Burlesque) and before that in a theatre on the side of the Ford Hotel and before that at University and Dundas

• the General Zionist – Workmen’s Circle – Labour Zionist concentration in the Cecil-Beverley Street area

• the scores of synagogues and shtiblach in the same few blocks

• the Kensington area before the Hungarian and Portuguese invasion

• the little bakery on nearby Fitzroy Terrace (an aristocratic name in keeping with its Kensingtonian neighbor) which specialized in bagels suspended on a string

• der roiter shneider, a red-bearded tailor on Spadina Avenue to whom mothers took their unwilling boys to be fitted for a yom-tov suit of clothes

• the Londoner Shul, a landmark on Spadina Avenue for decades, a house of worship bearing the name of Old Albion (Anshe England) but singularly devoid of accents either Cockney, BBC or Oxonian (though I do recall a Jewish Gael who worshipped there)

• the Rebbes Hoif on Huron Street, now the Coach House Theatre, where the Galician dynasty of Stretten reigned and where beer, dancing and other frivolity prevailed once a year on Simchas Torah

• the intellectual intensity of the political wiseacres who played chess and dominoes in obscure Spadina Avenue “stationery stores”

• the every-hour on-the-hour minyan of the St. Andrews Synagogue (not named after the Scottish patron saint but really the Minsker Shul on that street), serving the garment workers who were mourners or had “yortzeit”

• the post-matinal kiddush served to the minyan in the cold grey of the morning as they unwrapped their tfillin

• the Hebraists who dropped around to Hymans to discuss the latest trend in the world of literature (and still do)

• the lectures by Leivik, Opatoshu, Zalman Schneiur, Melech Ravitch, Efroim Auerbach and especially the visits to Toronto by Sholem Asch and the whole gossipy string of eye-winking anecdotes and episodes his visit would give rise to

• the “Gentiles Only” placard on Brooker’s Barbecue at the Humber River to the west of Toronto

• the “Swastika Gang” at Kew Beach in 1933 and later the “Pit Gang” at Christie Pits and the open warfare with them and the Jewish boys

• the Pride of Israel picnics – truly great “bashes” held each summer at Long Branch Park with a young, prematurely greying alderman-lawyer named Nathan Phillips as guest speaker

• the great thrill in 1930 at the election of Sam Factor in Toronto West-Centre (later called Spadina) over Tommy Church who was considered unbeatable in other ridings

• the bright young men who were rabbis of the “Bond Street Synagogue” in the 1920s – Brickner, Isserman, and Eisendrath – who inveighed against strapping in the schools and who drew hundreds of Gentiles to their Sunday morning sermons

• the Kehilla hearing in 1932 before Judge Tyler where a string of rabbis were paraded before the court and interrogated on their earnings and income

All of these, too, were among the sights, sounds, impressions and images of a colourful Toronto Jewry of “just yesterday.” ♦

Reprinted by permission of the Kayfetz family. © 1967, 2012. All rights reserved.