Dr. Neil Rosenstein of New Jersey has been researching his roots ever since his childhood in South Africa. Born in Cape Town in 1944, he studied medicine there and interned in Israel, but despite the rigours of medical school he never abandoned his family tree research for long. A surgeon, he jokingly describes his medical practice as a hobby that interferes with his genealogy, and compares the genealogical obsession to a malarial fever “that may disappear temporarily but never goes away completely.”

Dr. Neil Rosenstein of New Jersey has been researching his roots ever since his childhood in South Africa. Born in Cape Town in 1944, he studied medicine there and interned in Israel, but despite the rigours of medical school he never abandoned his family tree research for long. A surgeon, he jokingly describes his medical practice as a hobby that interferes with his genealogy, and compares the genealogical obsession to a malarial fever “that may disappear temporarily but never goes away completely.”

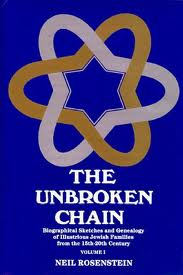

The author of a shelf of books relating to rabbinic roots and Jewish genealogy, Rosenstein’s magnum opus is The Unbroken Chain. First published as a single volume in 1976, the study was extensively reworked and republished in 1990 in two large volumes of about 1,350 pages, with perhaps four times the content of the original.

The Unbroken Chain traces the lineages of many distinguished rabbis, talmudists and prominent Jewish personalities, and shows how their families are linked. Through meticulous research, Rosenstein connects Karl Marx, Helena Rubinstein, Martin Buber, Moses Montefiore, Moses and Felix Mendelssohn and other accomplished Jews. Key branches of the same family tree involve the famous Katzenellenbogen, Auerbach and Landau rabbinical lines.

The Unbroken Chain traces the lineages of many distinguished rabbis, talmudists and prominent Jewish personalities, and shows how their families are linked. Through meticulous research, Rosenstein connects Karl Marx, Helena Rubinstein, Martin Buber, Moses Montefiore, Moses and Felix Mendelssohn and other accomplished Jews. Key branches of the same family tree involve the famous Katzenellenbogen, Auerbach and Landau rabbinical lines.

The figure at the top of the pyramid is Rabbi Meir Katzenellenbogen of Padua (1482-1565), otherwise known as the MaHaRam of Padua, whose descendants gave rise to the Ger, Bobov, Horowitz and other leading Hasidic dynasties of 18th-century Europe. Not too surprisingly, there are strong hints of royalty in the family as well. Rabbi Meir’s grandson, Saul Wahl Katzenellenbogen, entered Polish folklore in medieval times by allegedly becoming “king for a day” during an inexplicable interregnum of seven months between Polish kings.

Rosenstein is himself connected to the “unbroken chain,” since his grandfather was a Katzenellenbogen. This does not put him into exclusive company, however, since he estimates that as many as half a million Jews alive today may claim descendancy from the Padua Rav. Rokeach, Horowitz-Margareten and Rothschild are other prominent names on the same tree.

Rosenstein’s other works include Latter Day Leaders, Sages and Scholars (“Zichron Le-Acharonim” in Hebrew), a compendium of more than 5,500 Jewish notables born in various localities between the late 18th and the early 20th centuries. With Rabbi C.U. Lipschitz, he co-authored The Feast and the Fast (1984), a translation from the Hebrew of portions of the dramatic biography of Rav Yom Tov Lipman Heller, a 17th-century Torah giant, complete with a genealogical appendix and index of more than 1,330 related families. In 1989 he and Charles B. Berstein wrote From King David to Baron David, a study of a Rothschild genealogy.

While legends of a descent from King David or Rashi, the medieval Torah commentator, persist in many Jewish families, such undocumented stories are usually problematic and best taken as legend. Rashi’s family tree has long been the focus of a scholarly debate in which Rosenstein, not surprisingly, has participated.

Finding an ancestral connection to a noted rabbi is one way that Ashkenazic researchers may sidestep the “brick wall” of about 1800, roughly speaking, before which Jewish communities in Russia, Lithuania, Galicia, Prussian Poland and other regions were not obliged to keep civil records.

Besides the books mentioned above, your rabbinical ancestor may be found in Otzar Harabanim, by R. Nathan Zvi Friedman, a biographical encyclopedia listing some 20,000 rabbis from the year 970 to 1970. Or try Meorei Galicia, by R. Meir Wunder, an encyclopedia of Galician rabbis and scholars. Easily accessible, the Encyclopedia Judaica also provides extensive rabbinical genealogies, including one for the Besht or Ba’al Shem Tov.

In centuries past, books written by rabbis often contained a page-long forward or approbation (“Haskamah” in Hebrew) outlining an illustrious lineage. A gentleman who claims descent from Rabbi Joseph Caro (“Shulchan Aruch”) recently showed me such a page from an antiquated book, outlining his yichus or lineage. Researchers often utilize pinkassim (Jewish communal record-books) and rabbinic responsa (letters) as well.

Interpretating such materials is not for beginners. The task requires a knowledge of written Hebrew and the ability to decipher Rashi script (a combination of Hebrew and Aramaic textual characters) and a host of arcane Hebrew acronyms. But for the dedicated researcher who finds a rabbinical route around the brick wall of 1800, no linguistic or cultural barrier of this kind is apt to stand in the way for very long. ♦

© 1996