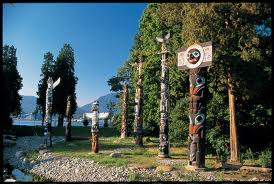

The largest urban park in Canada and the third largest in North America, Vancouver’s Stanley Park is still “half savage and half domestic” as writer James Morris noted a century ago. The historic park offers visitors a compelling mix of dense natural woodlands and well-pruned flower gardens, fierce aboriginal totem poles and a genteel Victorian-style seaside promenade, as well as various family attractions like the Vancouver Aquarium, a children’s petting zoo and panoramic views of downtown Vancouver and the mountainous North Shore.

The largest urban park in Canada and the third largest in North America, Vancouver’s Stanley Park is still “half savage and half domestic” as writer James Morris noted a century ago. The historic park offers visitors a compelling mix of dense natural woodlands and well-pruned flower gardens, fierce aboriginal totem poles and a genteel Victorian-style seaside promenade, as well as various family attractions like the Vancouver Aquarium, a children’s petting zoo and panoramic views of downtown Vancouver and the mountainous North Shore.

Situated on an elevated peninsula that juts into Burrard Inlet, the park receives some eight million visitors annually, and not only during the busy season from May through September. This winter, as in previous years, a Miniature Railway runs through a section of park where the trees have been decorated with Christmas lights and seasonal displays.

The train “is a lot of fun and very popular,” says Terry Clark, an employee of the Vancouver Board of Parks and Recreation, which administers the park.

Visitors may stroll, jog, cycle, skateboard or rollerblade along the 10-km Seawall that encircles the park and affords convenient access to its most popular attractions; bicycles may be rented (in season) just outside the park entrance. The Stanley Park Scenic Drive, which circles the park, likewise provides convenient access for motorists. Eager to reduce the number of cars on this one-way road, officials plan to introduce a free shuttlebus service within the park next spring.

Visitors may stroll, jog, cycle, skateboard or rollerblade along the 10-km Seawall that encircles the park and affords convenient access to its most popular attractions; bicycles may be rented (in season) just outside the park entrance. The Stanley Park Scenic Drive, which circles the park, likewise provides convenient access for motorists. Eager to reduce the number of cars on this one-way road, officials plan to introduce a free shuttlebus service within the park next spring.

Most visitors don’t stray far from the most popular attractions, which are situated close to the W. Georgia Street entrance. Foremost among these is the famous array of seven totem poles beside Brockton Point, some towering more than 13 metres high, each representing a different British Columbian First Nation. Moved here from coastal villages, the totem poles serve as a reminder that aboriginals occupied the peninsula as recently as 150 years ago. Extensive middens and other archaeological sites in the park, which visitors are forbidden to excavate, date back 400 years and more.

Brockton Point is said to be the most visited tourist spot in the Vancouver area, indeed in all the lower mainland. If so, the highly-rated Vancouver Aquarium — home to some 9,000 sea creatures including dolphins, octupuses, crocodiles and beluga and killer whales — must rank a close second.

The Vancouver Zoo was also located here until 1993, when a referendum called for it to be closed; today, after much downsizing, all that remains is one lone polar bear. In its place is the children’s petting zoo, a farmyard compound of domesticated animals like ponies, goats, cows and sheep, representing unusual heritage breeds.

With an area of about 1,000 acres, Stanley Park is larger than New York City’s 800-acre Central Park. It is also larger than Montreal’s 500-acre Mount Royal Park and Toronto’s 400-acre High Park put together. For visitors prepared to abandon the beaten paths for rougher nature trails, Stanley Park offers some outstanding naturalist sites the likes of which can’t be found in any of these other parks.

With an area of about 1,000 acres, Stanley Park is larger than New York City’s 800-acre Central Park. It is also larger than Montreal’s 500-acre Mount Royal Park and Toronto’s 400-acre High Park put together. For visitors prepared to abandon the beaten paths for rougher nature trails, Stanley Park offers some outstanding naturalist sites the likes of which can’t be found in any of these other parks.

While much of the area was logged in the mid-19th century, some trees were considered too big to mess with and were spared the axe. Deep in the park interior are several stands estimated to be 800 to 1,000 years old. One tree, known as the National Geographic tree, is thought to be the biggest cedar tree in the world.

There are no signs to direct visitors to these huge monument trees. “We let people find them on their own,” says Clark. But a map showing their locations is available from the information booth inside the park entrance.

More accessible stretches of West Coast forest are located near Prospect Point, a promontory offering postcard-perfect vistas of the Lions Gate suspension bridge, downtown Vancouver, the North Shore and some islands in the Georgia Strait. The neighboring woods contain evergreens and conifers laden with moss, damp and dripping; also some big-leaf maple and alders.

While untamed nature can be awesome, the park’s gardeners have proven adept at creating domesticated beauty, such as the Ted and Mary Gregg Rhododendron Garden. In season, the garden features a profusion of flowering magnolias, camelias and rhododendrons, whose beautifying effect on the adjacent 18-hole Pitch and Putt has given it a reputation as one of the most beautiful golf courses in the world.

Other attractions of the park include Siwash Rock, a giant flowerpot rock formation at the water’s edge, the Brockton Point lighthouse, the Lost Lagoon nature house and freshwater wildlife reserve, and several pools and sandy beaches that are open from Victoria Day to Labor Day. The Brockton Cricket Pitch, which consists of an old pavilion and cricket lawns, is where locals in quaint white suits indulge in England’s peculiar version of baseball when the weather is warm and dry.

The quintessential spot for a picnic or barbecue, Stanley Park also boasts several restaurants. Near the rose garden, the Stanley Park Pavilion is a nice spot for a light lunch or high tea. Near the golf course, famous Vancouver chef Karen Barnaby presides over the Fishhouse Restaurant. Near Third Beach is the Ferguson Point Tea House, the park’s most fancy restaurant.

Stanley Park is open year-round and admission is free. From downtown, it is accessible via a reasonably short cab ride or via bus #52. ♦

© 2002